Question: I’m considering getting married but I’m concerned about how this might conflict with my practice (she is not a Buddhist). How can you come to terms with attachment and ultimately renounce it, AND be married? I’m confused. Please help if you can.

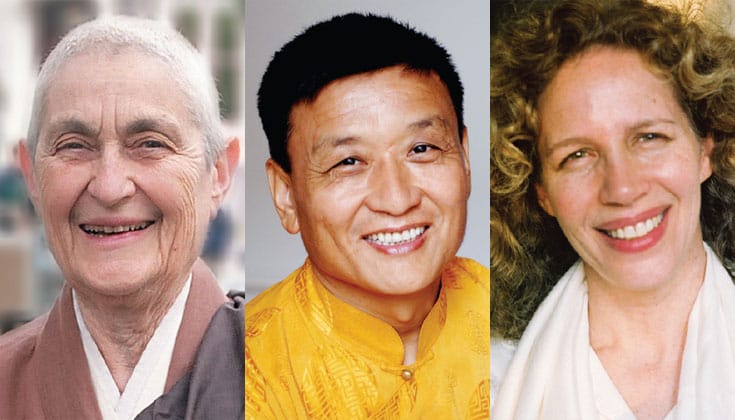

Narayan Helen Liebenson: If you were to choose not to get married, do you think that would do away with the question of attachment? There are charming stories about monks being attached to their one bowl or the color of their robe. Some of us are quite attached to our teachers. One can even be attached to the concept of renunciation. As you can see, whatever form we choose, it’s not so easy. We are adepts at clinging. Attachment is the problem, not the object of our attachment. Sometimes people try to deal with the suffering of attachment by avoiding commitment. This is called fear, not liberation. In this case, the point is not to let go of your partner but of the suffering that arises because of wrong understanding.

Being in an intimate relationship can be a wonderful invitation to discern the difference between attachment and love. In intimate and committed relationships, we can see the ways in which we basically think the other person should be like us. We may see the ways in which we secretly—or not so secretly—assume that the other person is there only to serve us. We have the opportunity to see the ways in which our love for that person has strings attached to it. And from this recognition, we can learn about selflessness and unconditional love. This selfless love can then be extended to all other beings, including those with whom we have no personal connection. All of this is in the realm of practice. And sometimes it is very hard practice.

The fact that your partner is not a Buddhist is of little importance, unless you hold this against her. It would only be a problem if she objects to the path you have chosen and does not want you to practice. Otherwise, Buddhist or non-Buddhist, what matters is how kind you are to one another. Sometimes practitioners say that their non-Buddhist partner is kinder and wiser than they are.

If you decide to get married, be wholehearted and committed in working within the form of marriage so that it becomes a practice and thus a chance to investigate the nature of suffering and liberation. The ways that we find ourselves attached become the very ground of practice. Instead of seeing the conflicts that inevitably arise between two people as inherent problems, we see that these conflicts bring our habits and tendencies into the light of awareness—and only in seeing is there the chance to let go.

Zenkei Blanche Hartman: You say you are “considering getting married.” Does that mean that you have spoken of marriage with your intended? Is she also “considering getting married” to you? If it has gone that far, I assume that you have shared with each other the values and concerns that are important to each of you and that there is significant common ground. I think that is very important to a lasting marriage. Perhaps some of the qualities she appreciates in you are informed and supported by your Buddhist practice and understanding.

You mentioned that “she is not a Buddhist.” If you have discussed your own values, concerns, and beliefs with her, she ought to have some sense of the importance of practice in your life. Your concern seems to be that somehow your practice and your marital obligations might conflict. Suzuki Roshi said to me once, “Sometimes when wife begins to practice, husband gets jealous like she had new boyfriend.” If this might truly be an issue, you owe it both to yourself and to her to sit down and discuss how you think your practice might affect your married life. I’m thinking of retreat time, sangha involvement, formal time with a teacher, your personal meditation practice, and so on. In other words, would the level of your involvement allow for ordinary family life? Since marriage means a most intimate commitment, do you see your continuing practice as supporting and encouraging the development of qualities which would make you a more present and responsive husband (and perhaps even a father)?

“Nonattachment” does not mean that we cannot love someone or be committed to a spouse or family. It means that we have understood that all conditioned things are marked by impermanence, not-self, and unsatisfactoriness (dukkha). Therefore, we do not cause ourselves misery by clinging to an idea of a substantial, permanent self or other, because we know that everything is changing and contingent on myriad causes and conditions. We make our best effort to stay in the present moment and to respond compassionately to whatever is directly in front of us, rather than cling to any idea. If you have an idea of marriage as something that might interfere with practice, rather than as a relationship that enhances your practice opportunities, you might have a concern for self in the back of your mind.

It is good and useful to examine our ideas of who we think we are and to realize that any definition limits whatever we are to less than the totality of just this, which includes the whole universe and is vaster than we imagine or are able to imagine. And it is useful to notice that clinging to ideas of practice, or of oneself, leads to suffering. So moment after moment, we make our best effort to just practice nonattachment or nonclinging in every situation.

Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: Any challenging situation in life can be workable when two qualities are present: openness and clarity. One question to ask yourself as you consider the commitment of marriage is, “Am I clear and strong in my dedication and commitment to dharma practice?” Another essential question is, “Is my partner open and respectful towards my developing relationship with the dharma?” If these two are present, I don’t see any problem.

If you lack strength or resolve, it’s important to avoid blaming your partner for your own inability to practice and feelings of guilt. But if your partner has a strong fundamental belief in another way and lacks tolerance for your view and practice, you should avoid this situation. If I make my belief and practice a priority in life and someone is going to interfere with that, I would not proceed with such a relationship.

In our ordinary lifestyle in the West, it is healthier to bring dharma practice into our lives than to avoid the challenges of life in order to practice the dharma. Developing a loving relationship with a partner can be an opportunity to bring dharma practice into everyday life. It is important to discover the basic goodness in all situations and to develop compassion for all beings. The daily opportunities that arise when living closely with another can be the spark that encourages this on a very practical level.

Buddhism says to renounce attachment and eventually achieve enlightenment. We don’t do that right away. We have that goal in mind and work in each moment with our attachment. Every single thing we do is attachment—wearing clothes, earning money, even asking a question. No matter which way you ask a question, it has to do with attachment. With no attachment, there are no questions! So in the relative sense, we work with attachment. There are obvious attachments we want to get rid of, such as being overly attached to our partner or greedy with our possessions. These attachments clearly bring suffering, and we should directly cut them. And there are some attachments that are useful—such as attachment to our dharma teachers and dharma practice, which will guide us and support us towards our final goal of attaining enlightenment for the benefit of all beings. In marriage, we can work with attachments every day and transform them into love or one of the four immeasurables: love, compassion, joy, and equanimity. Being in relationship provides ample opportunity for that process of transformation.