In the year of 1957, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening, which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life. At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music.

– John Coltrane, liner notes in A Love Supreme, 1965

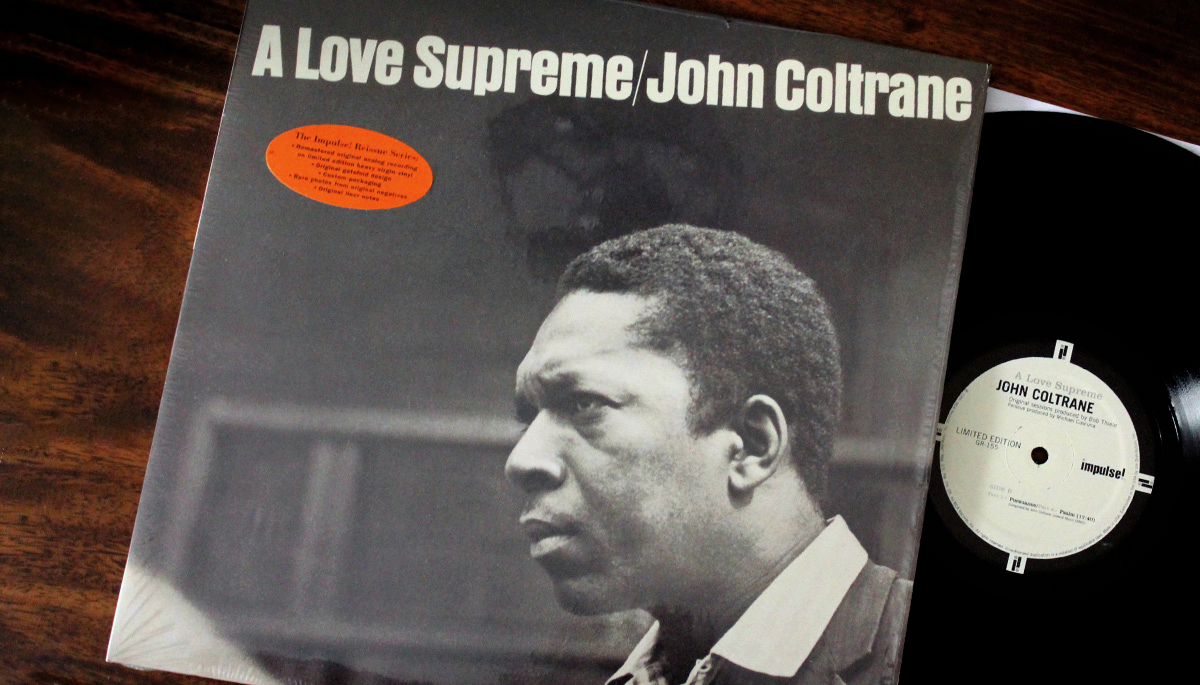

I was in high school when someone lent me John Coltrane’s album A Love Supreme. Coltrane recorded it in 1964 and it’s considered one of the most acclaimed jazz albums in history. They knew I was a musician and was also interested in spirituality since my mother died when I was 14. As a second generation Asian American, questions of identity and expression were also central within my own life and music.

Yet, when I first listened to the album, I honestly didn’t enjoy the experience. I remember thinking there was nothing I could use immediately in my own performances.

Like a koan, trying to engage Coltrane’s album with a linear, cognitive agenda was unsatisfactory.

The album initially frustrated me like the buddhist koan “show me the sound of one hand clapping.” I didn’t know much about Coltrane’s life or the album. The arrangement of A Love Supreme combined elements of modal jazz (which I enjoyed because of its intricate, predictable structure) and free jazz (which I did not enjoy because it broke conventions).

Most music has a structure and purpose leading to a resolution. I would listen and learn the chord changes to reproduce the structure and resolution for others to feel. I could also reap affirmation of my own mastery from those experiencing what I produced. But like a koan, trying to engage Coltrane’s album with a linear, cognitive agenda seeking easy conclusions for the benefit of my own self-worth was unsatisfactory. I remember returning the album quickly.

Many years passed since that initial exposure to Coltrane. My own music practice grew along with sitting meditation, which settled my own restlessness. What sparked a return to A Love Supreme was Coltrane’s quote about his awakening in 1957.

Coltrane was born in a segregated North Carolina in 1926. At an early age, John’s family suffered a series of significant deaths, devastating his family. Because of this, Coltrane took up the alto saxophone. He began his famous discipline of practicing obsessively as if it would bring his father back or restore stability to his life.

Coltrane was known for his relentless “sheets-of-sound” playing that mirrored his pursuit of the mastery of his instrument. He also battled intense compulsions, such as his heroin addiction, that initially soothed his suffering but became paths of self-destruction.

Coltrane resolved to quit his heroin addiction cold turkey after being fired from Miles Davis’ band in 1957. With only family support, he fasted and isolated himself with no medication or medical intervention. This event was so harrowing, his daughter Syeeda believed he was going to die that night. After more than a week, he emerged free from addiction but changed markedly in demeanor and even playing style.

Listening again to the A Love Supreme with this new understanding, I tried to hear and feel Coltrane’s life within the album. What did he encounter in 1957 amid all of his suffering that mirrored much of my own? What I noticed arising within me as I listened was an invitation rather than declaration; questions rather than instructions.

The album is a suite in four sections: “Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalm.” The movement of the suite suggests a spiritual pilgrim acknowledging the divine source of everything, resolving to pursue it, and rejoicing in what is ultimately found.

Opening the album, “Acknowledgement” is a four note melody which Coltrane plays, then chants, the phrase “A Love Supreme” over all 12 keys. Biographer Lewis Porter explains that Coltrane is “telling us God is everywhere – in every register and every key – and he’s showing us that you have to discover religious belief. You just can’t hit someone over the head by chanting at the outset – the listener has to experience the process and then the listener is ready to hear the chant.”

In the poem and in Coltrane’s playing, there is no separation from our source.

“Resolution” follows as a swinging second movement with the fanfare and excitement as one resolves to begin a perilous journey to seek this truth. The drum solo at the beginning of “Pursuance” sets the tone of the effortful, hurried motion of the third offering. A chase ensues which is not always steady, consonant, or easy – mirroring Coltrane’s own spiritual search.

The album concludes with “Psalm”: a musical narration of a prayer/poem he includes in the liner notes. The mood changes to whole notes and simplicity; grandeur and gravity. “Psalm” has no chord progression or steady beat as his solo is the syllabification of his poem of humility and gratitude.

Words, sounds, speech, men, memory, thoughts, fears and emotions – time – all related … all made from one … all made in one….ELATION-ELEGANCE-EXALTATION.

-“Psalm” by John Coltrane, liner notes of A Love Supreme

Initially, I wasn’t ready to hear the chant. I was holding onto my own hurt and had my own agenda. I had not yet traveled far enough to be open to transcending the conventions which were my only reality. This understanding came rushing back hearing the chant “A Love Supreme”. Each of the following tracks brought a wave of memories and energy back to my body in remembering my own pilgrimage: the determination to seek the source to all my questions in “Resolution”; the dead-ends, restarts, and glimmers of hope in “Pursuance”.

But as “Psalm” began, my breath became settled into long notes and spaciousness. In between cymbals and waves crashing was Coltrane’s voice held by something larger. In the poem and in Coltrane’s playing, there is no separation from our source. He expressed this is our true nature as well as the true nature of all things. There is nothing to do here except receive the boundlessness of this understanding. I remember feeling he wasn’t playing this for me or what I thought. Rather, I was being invited into this intimate, liberating connection in my own way. This truth already exists within me. Could I remember and release myself to it?

The invitation I now heard in the second listening less like a sermon and more like the sand mandalas associated with Tibetan Buddhist monks. These mandalas are created with beautiful intricacy from well-trained artisans. They often contain support for those meditating upon them with embedded references on the mental states toward enlightenment.

One can engage the sand mandala on many levels; its beauty, its precision, the mastery required to produce it, or the patterns and protection it offers towards awakening. But in the end, we cannot hold onto any of these as the mandala is destroyed and dispersed as a reminder of our own impermanence and return to our primordial source. Like a sand mandala, A Love Supreme was rarely performed in public after the album release. There are only two known live recordings of the suite. The band soon changed composition later that year and Coltrane died of cancer in 1967.

What arose for Coltrane after his own spiritual awakening and on “A Love Supreme” seemingly parallels Bodhicitta — “awakening or way-seeking mind” that seeks to purify the poisons, feels the suffering of others, and then endeavors to be a benefit for others. It humbles me to conceive of Coltrane’s own wordless, breath-centered practice through his horn becoming an instrument of awakening through this album. If this may be so, A Love Supreme may ask of us not to copy, compete with, or congratulate Coltrane for his journey. Rather, may our own “Way-Seeking Mind” awaken freely to the true nature that connects us all, our own practice for the benefit of all.