Buddhism has long asserted a connection between the heart and the mind. The Sanskrit word citta and the Japanese word kokoro each translate to English as both “heart” and “mind.” Now, Buddhist researchers are trying to identify that connection.

“In many Buddhist teachings, they talk about the connection between the mind and the body, brain, and heart,” says Venerable Sik Hin Hung, a Buddhist monk and the director of the University of Hong Kong’s Center of Buddhist Studies. “There are obviously connections between the mind and the brain. We wanted to know: is there a way to find a connection between the mind and the heart?”

To answer that question, researchers monitored activity in participants’ brains and hearts. Then they had the participant practice mindfulness meditation. In a study published in Neuroscience Letters the researchers reported that mindfulness meditation reduced chaotic activity in the brain and the heart.

“Activities of the brain and heart became more coordinated during MBSR training,” reported the authors. “Mindfulness training may increase the entrainment between mind and body.”

“We wanted to know: is there a way to find a connection between the mind and the heart?”

Based on that finding, the researchers believe that science could be used to confirm that there is a definite heart-mind connection. They are hoping to use the same tools to measure other Buddhist experiences, like chanting, jhana meditation, and perhaps even enlightenment.

“Is there a way to understand enlightenment scientifically?” Hung wonders with a chuckle. Enlightenment is loosely defined, Hung acknowledges, and has stages. But, nonetheless, he says scientists might be able to measure it.

“By understanding the ultimate law of the universe, the Buddha was able to eliminate his defilements: greed, hatred, and ignorance. So, one way to measure if a person is enlightened is to measure whether he has any defilements. Does he still have greed, hatred, and ignorance? Does he still exhibit stress when he looks at something horrible? When you show him sexy pictures, does he still exhibit desire?”

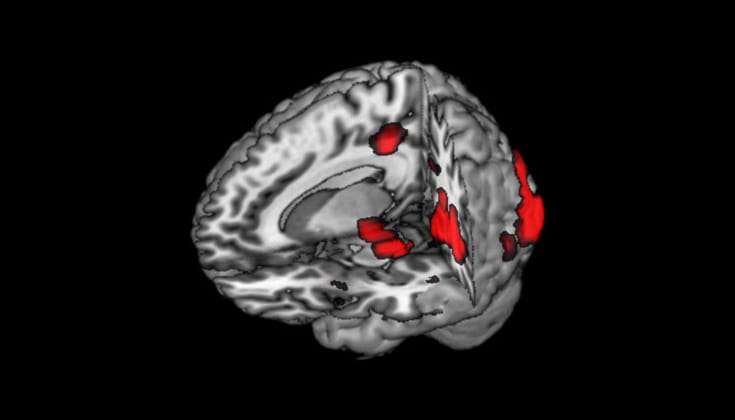

In an unpublished study that explores this question, Hung and his team studied the brain of an experienced Buddhist meditator as he went through the eight stages of jhana practice — an advanced form of Buddhist concentration meditation.

“Usually our brain is disorganized. When he was going through the jhanas, it seems that his brain waves — alpha waves and gamma waves — became more synchronized. But we don’t know what it means yet. We only have one person who is able to do that. One person is not enough data.”

The researchers are also using the tools they developed in the mindfulness study to scientifically investigate the effects of other Buddhist practices. In another study, of twenty-one Buddhists, researchers studied the brains of participants as they chanted either “Amitabha,” the name of a Buddha, or “Santa Claus.” Chanting “Amitabha” was found to help modulate brain responses, where “Santa Claus” did not.

“The Buddha was able to eliminate his defilements: greed, hatred and ignorance. So, one way to measure if a person if a person is enlightened is to measure whether he has any defilements.”

“Many people use mindfulness, but people are not aware of the benefits of chanting,” says Hung. “Chanting Amitabha or Om Mani Padme Hum or even Holy Mary is just as effective in dealing with psychological suffering.”

Hung says Buddhism is at the core of all of the center’s work. “I’m a Buddhist monk. Buddhism has always incorporated what is important at the time. When people became interested in logic, there came Buddhist logic. When people were interested in mantra, there came along Buddhist mantra. Now, people are interested in science. We want to find ways to communicate with people using the latest scientific methods and knowledge.”

Hung and his team are not alone in that pursuit. Many other researchers have explored the effects of Buddhist practices and the fidelity of Buddhist theories. In addition to a wealth of research on the benefits of mindfulness meditation, researchers have found that exposure to Buddhist ideas makes people more tolerant and compassionate; that there is no fixed “self”, as expressed in the Buddhist concept of anatta; and that mind may be an intrinsic property of reality.