Connection in Isolation

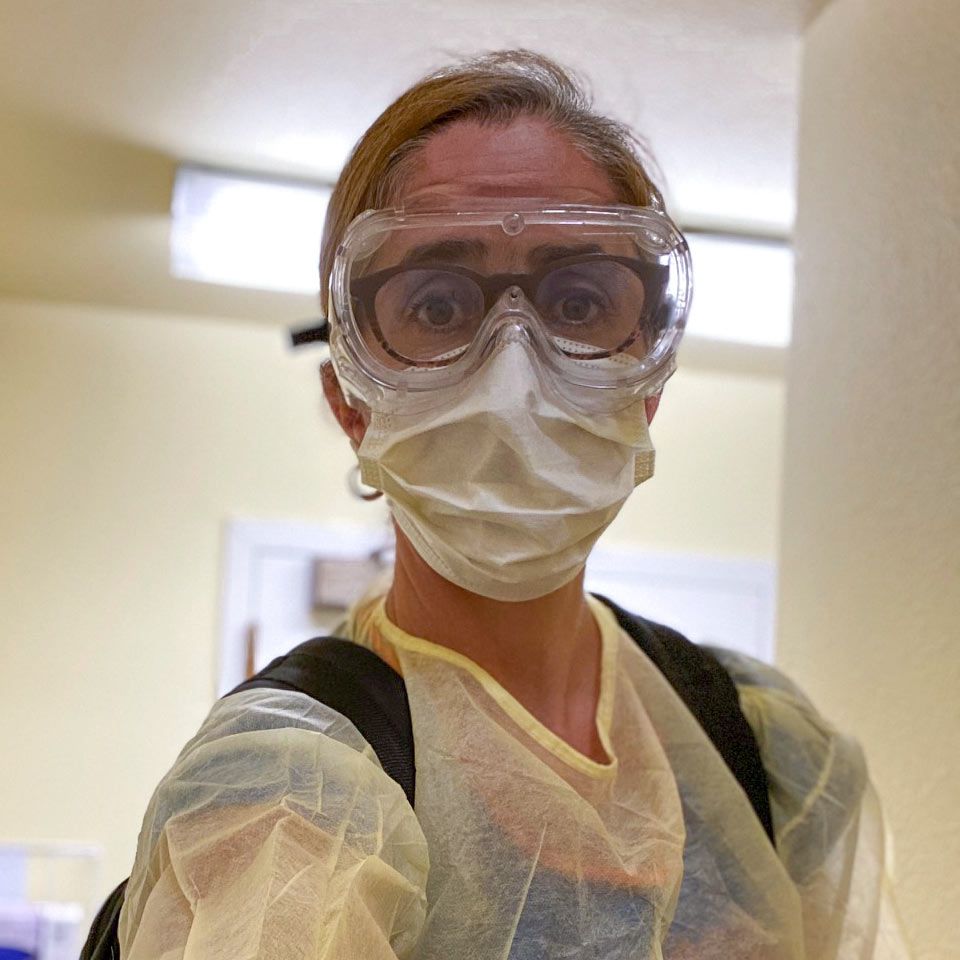

Coronavirus has made the world of hospice care even more intense says Joanne Laurence, a hospice and palliative care chaplain. Many patients are experiencing a lack of connection in isolation, which is where essential workers come in.

When I called the family of a new hospice patient, a woman dying of end stage dementia, I spoke with her daughter, Rosie. I told her I planned to visit her mother in the assisted living facility.

“That means the world to me. That makes my day,” she said, thanking me. Family are currently restricted from visiting the facility due to the coronavirus pandemic. Rosie’s mother is declining rapidly, and she is afraid she won’t be able to be with her through her dying process. The truth is, she likely won’t. We expect the virus to outlive her mother’s prognosis.

We are all vulnerable and afraid, including me.

I could hear her choke up as she expressed her vulnerability to me. Rosie is one of thousands of family members in the US who are currently separated from their loved ones. These visiting restrictions are in place to attempt to keep people safe. I agree with them wholeheartedly, but I’m also aware of the suffering the separation brings. In the absence of family, many in assisted living homes are still receiving good care, but some are not. Even so, there is something medicinal about seeing the ones you love in person. Holding them, kissing them, and bringing them food, flowers, and gifts all cultivate a sense of connection. This connection is lacking for so many right now. I fear the ripple effect of the trauma of this isolation and disconnect alone.

This is where we, the ‘essential workers,’ come in. Chaplains, nurses, social workers, aides, doctors and many more are still granted permission to serve those in need. It’s not possible for us to tend to all needs, but we work hard to tend to all that we can. The world of hospice care is intense, and coronavirus has made it even more so. I am now acutely aware of the Buddhist teachings of impermanence and interrelatedness. We are all vulnerable and afraid, including me. None of us are exempt from this vulnerability, even those with professional name tags. The realities of the collective angst are never far from my lived experience. I too may fall ill before this is over, but I know I was called to chaplaincy and end-of-life-care — I was called to be here in this moment. I pray for the strength and health to be able to continue onward, doing what I can to ensure the wellness and safety of all beings.

This Is a Collective Work

The coronavirus crisis is revealing our interconnectedness in stark terms, says Trent Thornley, executive director of the San Francisco Night Ministry. He shares how he and the organization are adapting.

My spiritual practice in this time of pandemic consists mostly of laying down in bed with my hands on my heart. I resist the urge to pull the covers over my head. Instead, I tune into the breath, sensations, and subtle energies of my heart center. Waves of irritation, grief, and anxiety arise and pass through my body. Though first personal, the feelings transform to a deeper pain, and a surprising tenderness, beating up from the heart of the world. Perhaps this is what the Tibetan teacher Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche meant when he referred to the “genuine heart of sadness.” I rest in the stream of the lineage as it carries me there.

I commit myself again to this world my tender heart loves so very much.

The coronavirus pandemic is revealing our interconnectedness in stark terms. This is certainly true of the San Francisco Night Ministry. Every night since 1964, our multifaith nonprofit has provided spiritual and emotional care on the streets of San Francisco and through our telephone “Care Line.” The Night Ministry serves an at-risk population that could easily succumb to the death throes of this pandemic. We are having to adapt to this new reality quickly. Not only are we transforming our ministry’s technology, we’ve found ourselves renewing our very sense of who we are and how we can be of service. Our phone Care Line is now needed more than ever, and we are working hard to expand this vital service. Yet, I am learning time and again that, as an individual, I can only do so much. Our little group, and indeed our greater collective, will rise and fall according to its own forces, and forces larger than any of us.

I’ve been thinking of the Bodhisattva Vow I spoke aloud some years ago. In the heart of this pandemic, the Vow feels unspeakable, beyond words, and beyond even the bounds of this life. In this moment, I commit myself again to this world that my tender heart loves so very much. I do my part to help, to the best that I am able, though the outcome is beyond my grasping. This is a collective work. Even though, from an ultimate point of view, we are all in this together, we are also differently situated, and sometimes vastly so. These days, the Bodhisattva Vow means to me the activity of manifesting the deeper truth of our togetherness, and striving to make it a reality for everyone. In those quiet moments, lying in bed, hands on my heart, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s words come to me: “I have faith in the night.”

Big Mind in the Parking Lot

Brent Beavers, currently in his year-long chaplaincy training, says we can face the moment we’re in head on, remaining both steadfast and empathetic in the face of the unknown.

Covid-19 has hit healthcare chaplaincy like a tornado, disrupting and scattering everything in its path. Chaplains normally encourage loved ones to visit their sick family members, and when a patient is near death their access is often unlimited. When coronavirus struck, this practice turned inside out. Visitors can no longer visit patients unless they are dying. Even then, all visits must be carefully considered.

To us, undiagnosed cases of coronavirus are “real” cases until we rule them out with a test. We refer to these cases as “rule-outs.” If a visitor is not a rule-out, we assess what their potential for exposure is. If a visitor is a rule-out, we must weigh the need for the visit against the need to reduce exposure to healthcare staff already risking their lives. Consumption of valuable and limited PPE resources only complicates this tension. Assessment of visitation must take into account the entire hospital full of patients and staff. The chances of them contracting Covid-19 grow each time a visitor enters the building.

Each day, each family, and each moment will bring a myriad of new ingredients.

This practice of limiting visits has brought up ethical and spiritual concerns. In overcrowded hospitals, patients are dying alone. The “Spiritual Care” team in which I serve has had to act as gatekeepers for visitations. On my first gatekeeper call to meet a family member who wanted to visit their dying mother, we met in the parking lot. Both the patient and visitor were Covid-19 rule-outs, but I still had to convey that the space beside a dying parent’s bed is no longer assumed a given right. “You mean to tell me my mother is going to die alone because of Covid-19?” they asked me, the tornado taking another virulent turn.

I am a little over five months into my Clinical Pastoral Education. As part of this education, I’ve been studying magnanimous, or big, mind. Dōgen Zenji, the Japanese founder of the Soto Zen school, defines magnanimous mind as “being without prejudice and refusing to take sides.” That morning, I read a line from the poet Rumi that also encapsulates its meaning: Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.

In this case, this field was an asphalt parking lot, and I was doing my level best. There I was in a tense vortex of staff, patient, and family, negotiating communication, safety, and compassion for the dying. I’ve been in many a vortex training as a Zen cook under Zen teacher Diane Eshin Rizzetto, but this time it was a matter of life and death.

Dōgen imparts to us in the Tenzo Kyōkun (Instructions for the Cook) that cooking for the community is cooking our very life. I’ve found chaplaincy training and Zen cook training to be not so different. We never know the nature and quality of the ingredients we will receive in this world — this pandemic makes this abundantly clear. The key lies in how we respond to these ingredients without the effect of conditioned biases, ideas, and emotions. This practice does not stop the storm, but changes our relationship to it. We can meet the storm head on, remaining both steadfast and empathetic. I have found that chaplaincy training, like Buddhist training, requires practice; that is, I continue to both act and reflect.

In the end, the visitor I met in the parking lot was able to be at their mother’s bedside as she died. “Thank God I was here,” they said, though this may not be the case for others. Each day, each family, and each moment will bring a myriad of new ingredients upon which to act and reflect, and I will continue to do so.

Come Back to the Truth of Ourselves

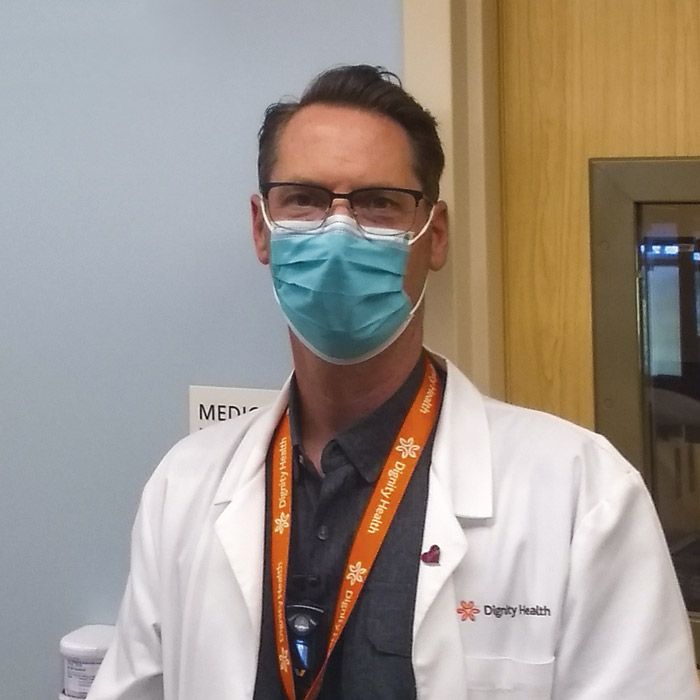

Jamie Kimmel shares how zazen practice informs his work as the staff chaplain at UCSF Health, and why now is a critical time to take care of ourselves.

As a staff hospital chaplain during this crisis, I am facing many new challenges providing spiritual care. My Buddhist practice helps me deal with these challenges, knowing that the nature of change, or impermanence, is the way of things. Every day at the hospital is not just different in the usual sense, but radically different.

The loved ones of our patients are not allowed inside the hospital, and many are experiencing more physical isolation than usual. When I provide care, I’m used to speaking with people at a closer distance than the recommended six feet. Body language serves as a cue for me, but now I talk with some patients in isolation units over the phone. I pay close attention to their voices, both what they are saying and the how they are speaking.

It’s critical that we take care of ourselves so that we can take care of others.

It’s amazing what we can do for someone when we are able to really pay attention. Zazen meditation has taught me that when I relax into where I am, there is much more happening than I’m usually able to see. For instance, recognizing when I am anxious, calm, angry, or tired, allows me to see how best to approach the coming day. The same goes for the patients I see. These days, I often deliberately move slower than usual, noticing more closely what is happening in the environment.

In this current situation, I find myself contemplating many things. I think of the safety of my loved ones, and the broken societal systems causing unnecessary suffering for so many. I try to remind myself that people are resilient — they contain within them the seeds of their own healing. By this I mean we each have the capability to come back to the truth of ourselves as an integral and active part of this universe. As a chaplain, I see that part of my role is to make space for that aspect of our expression. I know that our connections sustain us even when we remain unaware of them. There is an aspect of us all that reaches out for this connection in isolation. These days, connection can come in many forms — talking to a chaplain, listening to the silence in the room, connecting with what is bigger than us, practicing art, or whatever it may be.

I feel a sense of solidarity with all workers in the hospital, who I have been more heavily supporting. They are all on the front lines of this crisis and it is an honor to be there with them. I am continually uplifted by the professionalism and integrity of our staff who still have their personal lives to contend with. I try to remind everyone that right now, it’s critical that we take care of ourselves so that we can take care of others. I know that I could not do this work otherwise.

The earth is still turning; springtime is upon us. My devotional practice to Kwan Yin when I get home from the hospital enables me to let go of the day and start fresh tomorrow. I know that I am not alone despite the isolation so many of us must contend with now. Taking care of myself in this way opens up the space to invite others into the connection that we all already share.

The four chaplains telling their stories here were trained at the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Berkeley. We would like to thank Daikajaku Judith Kinst of IBS and Gesshin Greenwood for their assistance with this article.

In the September 2020 issue of Lion’s Roar magazine, an error went undetected in this story. Our sincere apologies to the contributors, Trent Thornley and Brent Beavers, whose photos were miscredited (Trent’s to Brents, and vice versa). The error has been corrected in our digital edition.