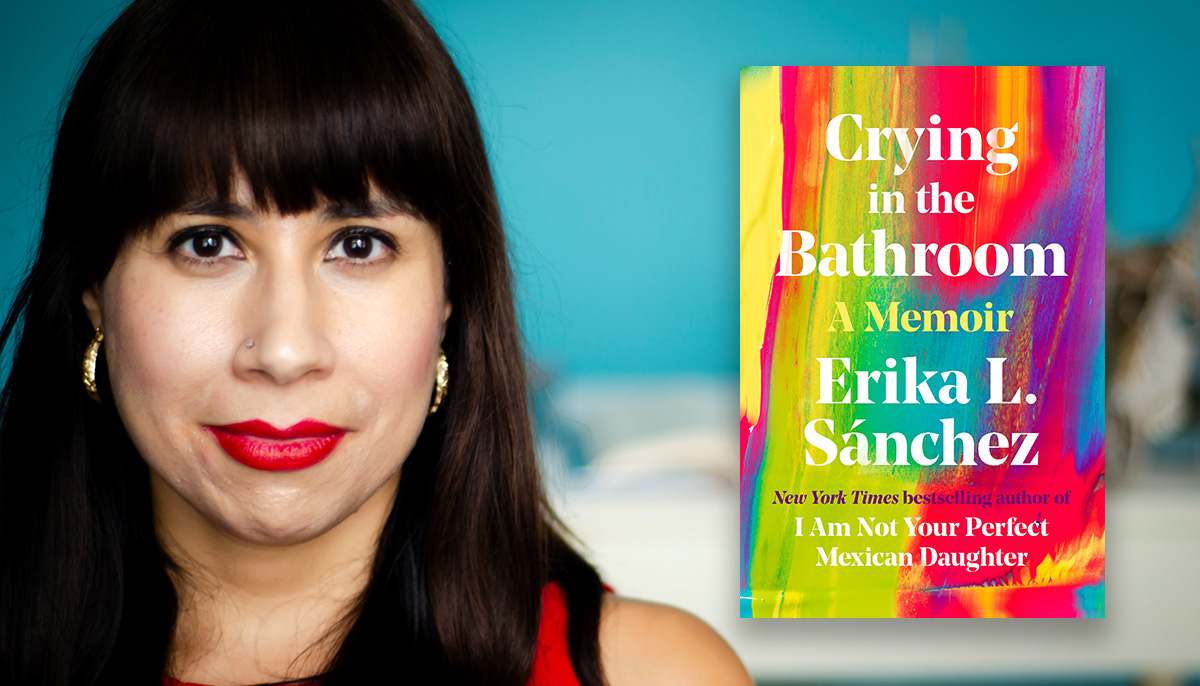

There isn’t just one way to talk about what it is like growing Latinx in America. The Latinx experience is complex and multifaceted. No matter how different our experiences may be, there are many commonalities shared. For instance, the sense of not fully belonging, I believe, is a central experience that we share in common. As immigrants, and children of immigrants, we are caught in this “in-between” space in terms of identity. Never being quite “American” enough in our new environment, and surprisingly, not being Latinx enough—Colombian enough in my case—to our families and friends back home. No matter what context we find ourselves in, there is an underlying sense of being an outsider, not quite fitting in. In a way, Erika L. Sánchez’s new memoir, Crying in the Bathroom, is for all the misfits who, like her, never quite fit in anywhere. Erika L. Sánchez is an award-winning novelist, poet, essayist, and author of I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter, a New York Times Best Seller, and a National Book Awards finalist.

Sánchez’s new book is a collection of personal essays where no topic is off-limits. Sánchez talks about what it was like growing up as the daughter of Mexican immigrants in Chicago in the 90s. She talks about the obstacles and challenges she faced and how they have influenced her throughout her life. Sex, spirituality, abortion, mental illness, and depression are just some of the topics that Erika discusses with a self-awareness that doesn’t hold back. While her experiences are deeply personal, the way she skillfully talks about them in her essays has a universal quality, making them accessible and relatable to the reader. The genuineness, humor, and wit woven throughout her writing will make you feel as if you are talking to her for hours, catching up with a long-lost friend.

Throughout her memoir, Sánchez also reflects on her relationship with her mother and how it shaped her—as a daughter and the mother she will become. Ultimately, Crying in the Bathroom is a brutally honest and insightful love letter to her daughter. It is an invitation to know her in a deeply intimate way in which she never knew her own mother.

I sat down with Erika to talk about her new book, her Buddhist practice, and how Buddhism has influenced her as a writer.

—Mariana Restrepo

Mariana Restrepo: Why did you write this book? What was the question that you were trying to answer?

Erika L. Sánchez: I never planned on it. Nonfiction never occurred to me until someone asked me to write for an anthology on ambition, so I wrote Crying in the Bathroom. I wanted to write essays about things that I cared about; things that were personal, political, the macrocosm, the microcosm, all of it. I wanted to write a collection of essays that spoke to women like me. Women who never fit in anywhere, women who were weirdos in their families, women who have been trying to find a way to exist in this world that is so hostile toward us and so many other people as well. I wanted to speak to young women and perhaps change their trajectories. I wrote the book I wish I had read when I was coming of age and trying to figure out my life and place in the world.

You describe yourself as a perfectionist with impossibly high standards and expectations of yourself. How did that affect the process of writing a memoir, where you exposed all aspects of your life, confessing all your failures and shortcomings for everyone to read. Did that hold you back?

I couldn’t have written that right after my depression. It would’ve been a terrible essay. But after a while, I was able to see the situation very clearly. It was cathartic emotionally; it hurt. But that’s what catharsis is. It is a painful purging. I also really enjoyed turning this horrible experience into something beautiful. Poetry taught me to find beauty in the ugly, and Buddhism too. Buddhism and poetry are in line with one another. At first, I just expelled it, then I had to rewrite it. I lost count of how many times I did that.

You often talk about how Buddhist concepts, such as “changing poison into medicine,” are relevant in your writing, particularly in your poetry. Could you talk more about this and what “changing poison into medicine” means for you and your writing?

I think a lot about karma and how I’ve been given this life. I am this person who descends from many people who have been very disenfranchised. The women in my family never had hardly any choices. I’m the first one born here in the United States. And so my life is so ripe for opportunity in some ways. I never would’ve thrived in Mexico the way I’ve thrived here. I always think about how arbitrary that is. Here I am, born in a place that makes me so lucky. But also not so lucky in the fact that my relationship with my parents is complicated and difficult.

We were poor, we experienced racism, and I have a mental illness… I felt that I had to do something with all of that. I was the first woman in my family to have an education–My mom only has a sixth-grade education. My grandmothers didn’t go to school at all. I feel it is my job to take those stories and turn them into something that people will feel seen by and feel connected to. It makes all the suffering have meaning. You can find wisdom in that. When I do that in my writing, it feels really good to process so much of my reality, my karma, and then turn it into something that can possibly liberate or heal people.

Your book discusses how Buddhism has allowed you to come to terms with your “self,” living life on your own terms and living your truth. What does it mean for you to live your truth?

That’s a good question. It’s a big answer, and the easiest way to approach it is to talk about what I’ve always wanted for myself as a girl, as a woman. I’ve always wanted to belong to myself first. I didn’t want to get married and just be someone’s wife. I didn’t want just to be someone’s mother. I wanted to learn, and I wanted to challenge. I was always a person who challenged the status quo, gender roles, and injustices in different forms. I felt angry about many things because we were living in a so-called democracy, but it doesn’t feel that way. And so, all I wanted was to have a dignified existence, not have to rely upon a man. I never wanted to be at the whims of a man, that scared me, and I’ve seen it, and it’s awful. I wanted to be a thinker, a writer, and a traveler. I wanted to make decisions about my own body, the way that I wanted to do whatever I wanted to do. That hasn’t changed for me. I still just want to be free. And to me, being free means making choices, having choices, first of all, because a lot of us at certain times don’t.

Did becoming Buddhist bring about a shift in perspective?

It shifted everything for me. It made me realize so much that I hadn’t confronted. The image of the mirror, the polishing of the mirror, comes to mind immediately because as soon as I started practicing, I was like, “Oh, I’m not really in love with my husband. I better change something because this does not align with who I am.” Buddhism has had me question many things in my life, and I had to make some tough choices. I chose to leave my marriage, live by myself, and pursue this writing career, no matter what, because I knew that was my calling. It clarified things for me, things that I had been lying to myself about.

In your book, you talk about how you tried out different forms of Buddhism when you first encountered it–first at a Tibetan Center, then at a Nichiren Center. Can you talk about that process?

I had always been so intrigued by Buddhism because, as a young person, I had a lot of inner turmoil, and I didn’t know how to address it; I didn’t know what to do with myself. Buddhism was perhaps this sort of far-away solution, but I never really pursued it until I was older. In my twenties, I went to a Tibetan temple but didn’t feel comfortable there; I wasn’t connecting to the dharma. It was so esoteric that I couldn’t feel anything about it. It wasn’t until I was introduced to Nichiren Buddhism by a good friend of mine. He was so joyful, authentic, wonderful, and intelligent. There was something about him that I really liked and felt inspired by.

At the time, I entered one of the worst depressions of my life. As I emerged from that, I started going to these meetings where people would chant together. The way that people had such camaraderie was beautiful.

When I read The Buddha in Your Mirror, the teachings were so clear. That was the book that really did it for me. Everything made sense to me–cause and effect, karma, being kind, all the things that seem so obvious but are not–it all clicked. That book really solidified things for me. A stranger bought it for me at the center’s gift store. He was just like, “You need to get this book because you’re new and I’m gonna buy it for you” And he was right, I needed it.

What does your practice look like nowadays?

I’m pretty lax right now. I’m being really patient with myself and not getting mad at myself for not always chanting. I also hold all the teachings in my heart.

Thinking about impermanence has made my life so much easier. That’s something that I had always struggled with, to really accept that life is always changing, and nothing is certain. Now, with that deep understanding, I feel my life is much better, and I have less anxiety.

Has your understanding of Buddhism and your practice changed since becoming a mother?

I see how important it is to change karma. I don’t want to pass on burdens or traumas to my child because it’s really unfair. I feel like it’s my responsibility to do the work all the time so that she has a happy life and so that I can be a good mother. In that way, it makes me more cognizant of the consequences that my trauma might have on her if I don’t address all of it.

What was your parent’s reaction when you converted to Buddhism, and how has it affected your relationship with your parents and family?

They didn’t fight me on it that much at all. They knew I would do what I was going to do. I had already rejected Catholicism, and they were mortified but just had to accept it. When I became Buddhist, my mom was excited because she thought it might help my depression and anxiety, and it did. Now she even occasionally asks if I’m still chanting.

How does Buddhism influence your work and creative process?

It makes me pay attention. It makes me more mindful of what is around me. I’m always looking for things that are beautiful or unusual or strange. I think that Buddhism, the practice of having to stop and reflect all the time, is great for paying attention to things that perhaps you wouldn’t otherwise notice. Mindfulness is important to me as an artist. With it, I absorb the world and let myself be moved by it. Transforming poison into medicine is what I do with terrible experiences. My suffering is turned into art. My suffering has become books that people read, that people feel seen by, that people love.

The interrelatedness of all things is something I’ve thought about a lot as a poet. When I read The Buddha in Your Mirror and started to understand the concept of everything being interrelated, it made sense to me because I had already thought about that for so long. Many different layers of the practice have helped me develop as an artist.