From being to the nature of time, Dogen explored the big questions. Four experts unpack some of his most influential concepts.

Being-Time: Everything in This Moment

by Shinshu Roberts

Awakened practice can only happen in this present moment. “Although the [dharma] might seem as if it were somewhere else far away, it is the time right now,” Dogen writes in his famed Shobogenzo fascicle Uji—Being-Time.

Understanding how this comes about is Dogen’s primary teaching throughout the Shobogenzo. Everything is simultaneously manifesting, he explains, both as this moment and as all moments that together make up the world’s functioning; this is the essential nature of the buddhadharma. A particular being-time/time-being, or dharma position, is a hologram that includes all of time(s) and being(s) as one event that cannot be separated.

The essence of being-time’s expression is compassion, wisdom, and skillful action.

Awakened response is integrating oneself with the specificity of each moment, which is intimately experienced as your life with self and others. While Dogen’s teaching about time-being/being-time is multifaceted, it is always about the concrete activity of each being’s life as it unfolds. Here’s an example from our human experience.

Imagine you are attending a meeting with a difficult coworker. You enter your hypothetical meeting with 360 degrees of possible action points of exit from each moment. Will your response be dictated by past ill will, or will you be able to be open, listening, and responsive?

As you enter this present-moment circle, there is the past “behind” you of all your previous experiences with your coworkers. Yet this moment doesn’t have to be defined by your past or by your future agendas. Since the moment in itself is already liberated, you have the possibility to respond without attachments. This freedom is the independent aspect of a being-time freed from past karma and future desires. Liberation can only happen in response to your present moment.

But if you are caught by your past experiences and expectations for the future, your exit from each moment will be quite narrow and probably unskillful. A big part of our practice then is becoming aware of when we are caught, and then changing course. Only when we can fully engage without being caught by the snares of our desire can we respond to each encounter with a liberated mind. That’s why it is important to stay awake and integrate ourselves with what is actually happening, not with what we wish would happen or what we are afraid will happen.

Dogen’s teaching on the unity of being-time, or reality itself, is vast. Uji discusses the various aspects of a dharma position: its independence, codependent arising, eternal presencing, universality, and flexibility as one mandala manifesting as this moment’s intimate response.

The essence of being-time’s expression is compassion, wisdom, and skillful action. Dogen’s teaching on being-time’s inseparability is not a philosophical treatise on time’s relationship to being; it is a primer on alleviating the suffering of self and other.

Monasticism: Training in Compassion

by Chimyo Simone Atkinson

The whole pure assembly should abide in mindfulness that everyone in the study hall is each other’s parent, sibling, relative, teacher, and good friend. With mutual affection take care of each other sympathetically, and if you harbor some idea that it is very difficult to encounter each other like this, nevertheless display an expression of harmony and accommodation.

—Dogen Zenji in Regulations for the Study Hall

During my time in Aichi Senmon Nisodo monastery in Nagoya, Japan, I shared a room with seven other Soto Zen nuns. It was so small I slept with my feet in the closet. The edges of our futons overlapped when we laid them out at night, and we had to arrange ourselves face-to-face and head-to-foot to fit in the cramped space.

We were Tenzo-ryo, the kitchen crew. Often we were the first to get up in the morning and the last to get to bed, keeping long work hours to feed the monastery and the frequent visitors.

By the end of a long day of kitchen work, practice, and study, we were all exhausted. My futon was the farthest from the door, and getting to the toilet in the middle of the night I had to carefully cross an obstacle course of prone bodies, doing my best not to step on a stray foot or hand. It made me very aware of how vulnerable we all were, and how trusting and how careful we had to be with each other just to get through the day.

Monastic training is not simply learning how to do ceremonies or studying the sutras, although these things are essential to our formation as priests. Learning to embody the compassion these ceremonies and sutras point toward is really the purpose of joining the intense environment of the monastic assembly.

In the monastery I spent very little time alone. I was in the company of my fellow nuns twenty-four hours a day. We had to move in harmony in order to function. All the activity of the monastery was focused on caring for each other—cleaning bathrooms, preparing meals, drawing baths, ringing bells for zazen. Nothing happened in those buildings that was not for the benefit of our fellow monastics.

I barely remember some of the ceremonies I was taught at the monastery. I can always look them up or find some reference book if need be. What has stayed with me are the memories of sliding my feet between those tender bodies in the dark, of preparing a tray of cups for tea, of a sister nun helping to straighten my robe. These are simple examples of the care and compassion that I believe we monastics are meant to pass on to our communities and disciples when we reenter the world.

Practice: Be the Buddha You Are

by Koun Franz

In Japan, I heard monks joke that “the only person to ever train in the way of Dogen was Dogen.” His monastic rules are so numerous and so precise they are almost impossible to follow. But there’s another side to it, which is that training in the spirit of Dogen is actually pretty simple. It just requires an unconventional lens on what practice is all about.

If you are already buddha, then how do you act?

At the heart of Dogen’s (many) teachings is the notion of practice–verification, sometimes referred to as practice–enlightenment. Essentially, this means that the fruit of what we do is precisely the thing we’re doing. In other words, we don’t practice to attain enlightenment. We practice because practice is enlightenment. In his language, we don’t train to become a buddha; we train as buddha.

In Fukanzazengi, his most famous set of instructions for zazen, Dogen wrote, “To practice the Way singleheartedly is, in itself, enlightenment. There is no gap between practice and enlightenment or zazen and daily life.” Here, we get a glimpse of how Dogen framed everything. Practice is enlightenment (it’s self-verifying); practice is also zazen; zazen is daily life. Therefore, everything we do, every action we undertake, can be practice. Enlightenment is built in.

This doesn’t mean, by the way, that there’s nothing to do. Practice means doing something; verification means there’s something to verify. The trick is to practice—whatever that is in this moment—free of the idea that there’s some reward.

If you visit a Soto Zen center, you’ll hear people talk about “just sitting.” When you bow, they’ll say, “Just bow.” Just sit, just bow, just chant, just study, just walk—in Dogen’s conception, these are not means to an end, stepping stones to some spiritual goal. They’re not part of a curriculum. Each thing is just this. Each thing is enough, just as it is. It’s complete.

We discover that completeness by taking it up in a wholehearted way—not just with our minds but with our bodies. We meet this moment with our hands and our posture and our breath, with the way we speak and the way we walk. “If you understand this,” wrote Dogen, “you are completely free.”

Dogen is famous for his dense, poetic writing—sentences and ideas that seem to turn in on themselves, sometimes leaving us unsure which way is up and which way is down. It’s beautiful stuff, some of the most challenging writing in all of Buddhism. Some are drawn to that, but I suspect many just find it too much.

But underneath it all is a single thought experiment: if you are already buddha, if you’re not striving to gain something, then how do you act? How do you take care with this moment—not in the abstract, but in the way you move, in the way you hold an object, in the way you open a door? Buddhas know the answer, and that means you do too. So just act like the buddha you are.

Being: Awakened by All Phenomena

by Seigen Johnson

I spend a lot of time engaged with the teachings of Dogen. For years, I literally carried his words with me nearly everywhere I went. My spiritual practice is deeply grounded in his teachings on the harmony of difference and equality—awakening through an intimate embrace of the universal and subjective not as separate phenomena, but as two qualities of all phenomena.

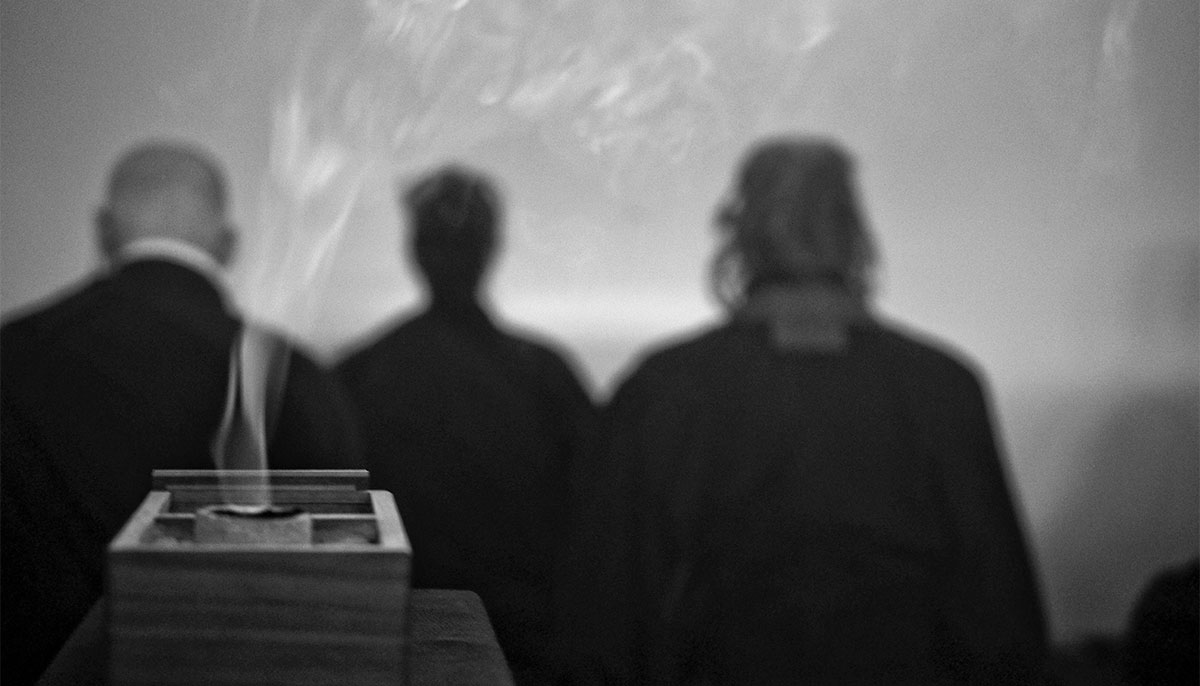

In my earliest days of practice with Dogen, I was struck by the balance in his expressions between the poetic and pedagogical. You hear his lyricism in his metaphors about the nature of phenomena: the moon in a dewdrop, the sands of the Ganges, the phenomenal expression of ash, the simplicity of a grain of rice. And then he offers unsentimental, practical instructions: how to sit and hold one’s posture during zazen, how to organize the kitchen, how to orient the space of the meditation hall. The lived example of Dogen points us to the fully integrated way of being: feeling oneness with all things through careful attention to the mundane activities of everyday life.

The sense of phenomenality—the philosophy that things only exist as they are perceived by consciousness and not independently—in Dogen is poignant for me as an African American woman who practices Zen Buddhism. Our nation’s conversation about the teaching of critical race theory, for example, brings front and center Dogen’s teaching that we are awakened by all phenomena. What is often missing in the conversation about CRT is the understanding that engaging with the legacies of slavery gives us access to and understanding of generational harm, but also reminds us of the extraordinary treasure trove of generational wisdom and healing born of that suffering. This is one of our nation’s most valuable cultural gifts to all of us.

Dogen wrote in Tenzko Kyokun (Instructions for the Cook): “Getting to eat a single grain of Luling rice enables one to see the monk Guishan; getting to supply a single grain of Luling rice enables one to see the water Buffalo [that Guishan will become]. The water buffalo eats the monk Guishan, and the monk Guishan feeds the buffalo…If you carefully inspect and exhaustively check [these matters], your understanding will dawn and become clear.”

These instructions invite more than just observation. Dogen invites aliveness and active engagement. For me, most importantly, he invites imagination and creativity.

I am earth, water, air, fire. I am you. You are me.

Recently, I was watching an episode of the Netflix series High on the Hog, which shares insights on the profound impact of African American food culture on the overall cultural landscape of the United States. Reaching back to Africa, the show’s host connects rice to the fabric of who we are today as a country. The rice I am now eating holds the history of the transatlantic slave trade and the beginnings of American capitalism. The rice I am now eating also nourished the people who survived that journey and who taught their captors to cultivate this grain in unfamiliar soil.

Awakening, for me, is understanding that the brokenness in the tragedy of the stolen (the grains and the people) is made whole in the transmission of knowledge, courage, and love. Across generations, across cultures, across time and space—Dogen’s wonderful gift is in guiding us all to this awareness.

I find incredible peace knowing that on my meditation cushion all things are possible if I allow myself to be grounded in an awareness of who I am—and also that I am more than who I think I am. I am earth, water, air, fire. I am you. You are me. Once we see it, we cannot unsee it, and we manifest togetherness in word and deed. We are together—phenomenal.