I doubt that many priests, let alone chaplains, have had the opportunity to perform an exorcism. I did once, and the best thing was—it worked.

A social worker called to ask me to help a young Japanese woman. She told me that the doctors were working on controlling the pain that came with the patient’s cancer, but the patient said that spirits had taken over her mind. That’s where the social worker thought I, as a hospice chaplain, might be able to help. I was glad that she trusted me, and I hurried to her office so we could talk about the case.

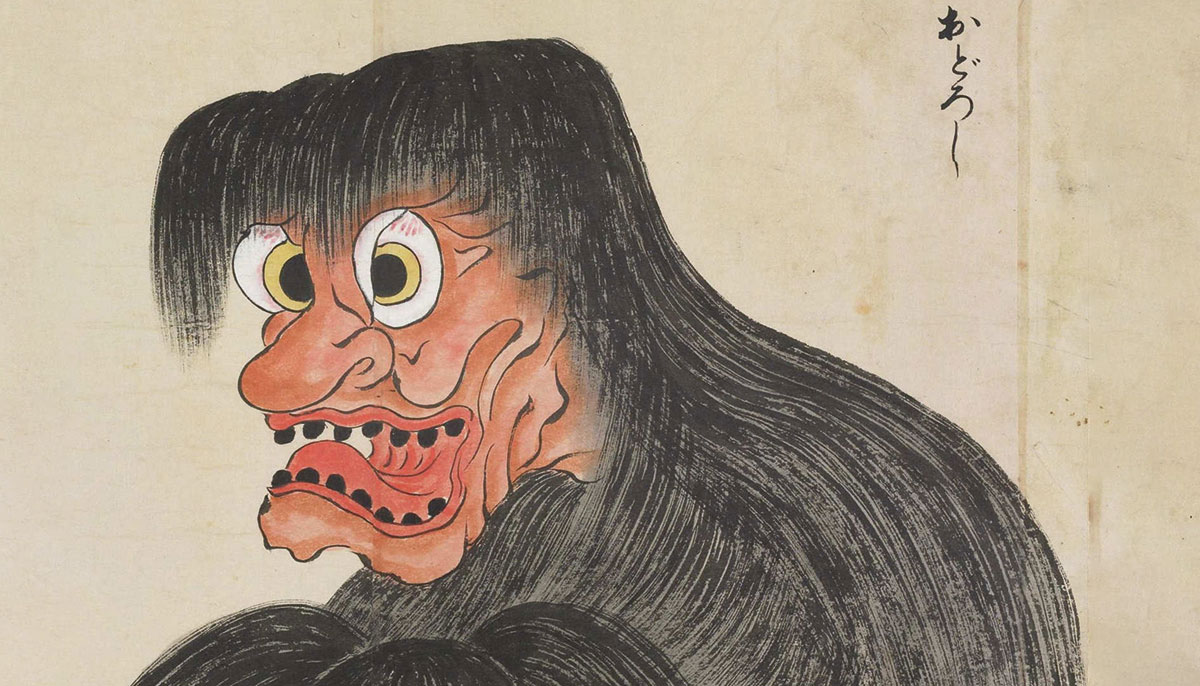

She explained that sometimes the patient was silent, head tilted, listening as the spirits spoke to her, and at other times she shouted in Japanese, apparently becoming the spirits and giving them a voice. She was living at home with her mother, who had come from Japan to take care of her. The spirits weren’t evil. The problem was their talking kept her awake all night. She and her mother were both exhausted.

I said that of course I’d do it—in fact, I had time to see the patient that very afternoon. I didn’t mention that, although I’d been thoroughly trained as a Zen priest, exorcism had never come up. But I felt sure I’d performed enough ceremonies that I could create one for the patient that would be convincing. We speculated about the cause of the phenomenon of the spirits, but what we thought in the safety of the office and what I saw when I entered the patient’s house were completely different.

I heard the patient before I saw her. She was at the end of a hallway, in the kitchen, howling and leaning forward on a walker, the top of her head pressed against the wall. I hurried to her, dropped my bag in a chair, and sat on the floor so my face was close to hers. I could see her arms quiver from the stress of holding up her body. Her face, when she turned it toward mine, was surprising; I hadn’t expected her to be so young and pretty.

I told her I was a priest, and that the social worker had sent me to help.

She answered, “They want to go to heaven.”

From this moment on, we were in her reality—and it was a relief to hear that the spirits were ready to go. Now all I had to do was provide a pathway for them.

I asked her whether she’d like to sit down. She agreed, and her mother and I helped her lower her body into a white plastic chair. I never learned why she had been standing in that tortured way.

She sat on one side of a large kitchen table. Her cellphone, wallet, pill bottles, notepads, Japanese newspapers, and other clutter were spread out before her. Her mother stood facing her, by the stove. She was a small, anxious woman, a long way from home.

I cleared off a couple of square feet on the short side of the table and said it would be our altar. I set out my ritual items: two fancy incense bowls filled with ash, a lit piece of charcoal in one; a candle; a figure of Manjushri poised to cut through all delusions with his sword; and a small figure of Kwan Yin, also known as Kanzeon, the bodhisattva of compassion.

I asked for flowers, and her mother rushed to the other room and brought back a vase with camellias and pine boughs. Realizing I’d left my bell in the car, I asked if they had one. They did not, and I decided to go ahead without it. What mattered now was maintaining momentum.

I cleared off a couple of square feet on the short side of the table and said it would be our altar. I set out my ritual items: two fancy incense bowls filled with ash, a lit piece of charcoal in one; a candle; a figure of Manjushri poised to cut through all delusions with his sword; and a small figure of Kwan Yin, also known as Kanzeon, the bodhisattva of compassion.

I asked for flowers, and her mother rushed to the other room and brought back a vase with camellias and pine boughs. Realizing I’d left my bell in the car, I asked if they had one. They did not, and I decided to go ahead without it. What mattered now was maintaining momentum.

The compassion of Kwan Yin was what we needed. I chanted, and suddenly the patient stepped toward me, shaking her head violently and yelling, “No! No! No!”

The rakusu is the garment that shows I’ve taken priestly vows. To begin, I put it on my head and said, as I have done hundreds of times when entering a sacred space: Great robe of liberation / Field far beyond form and emptiness / Wearing the Tatagatha’s teaching / Saving all beings.

I explained that I was going to perform a Buddhist ritual to help the spirits inhabiting the patient go to heaven. I asked the patient and her mother to do three bows to the altar with me. Lighting a stick of incense, I pressed it against my forehead and the foreheads of the Manjushri and Kwan Yin statues, and placed it upright in the first incense bowl.

Then I began chanting and putting pinches of incense chips on the red-hot charcoal in the second bowl to create clouds of smoke. The room began to smell wonderful. My voice filled the space as I chanted to Kwan Yin: Kanzeon / namu butsu / yo butsu u in / yo butsu u en / buppo so en / jo raku ga jo / cho nen kanzeon / bo nen kanzeon / nen nen ju shin ki / nen nen fu ri shin.

That is, in English: Kanzeon! At one with Buddha. / Related to all buddhas in cause and effect. / And to Buddha, dharma, and sangha. / Joyful, pure, eternal being! / Morning mind is Kanzeon. / Evening mind is Kanzeon. / This very moment arises from mind. / This very moment is not separate from mind.

The chant is simple and can be repeated endlessly. The compassion of Kwan Yin was what we needed. I chanted, waiting to see what would happen, when suddenly the patient cried out, rose from her chair, and stepped toward me, shaking her head violently and yelling, “No! No! No!”

She clutched my upper arms. I leaned forward and grabbed her above the waist to keep her from falling. I kept chanting. She kept shaking her head. Her short black hair, inches from my face, smelled clean and fresh. I somehow held her body with one arm so I could use the other to put more incense on the charcoal. The smoke billowed in the room and I spoke to the spirit, loudly, firmly, invoking all of the authority I had in me:

“You hungry ghost, haunting ladies on this plane, it’s time for you to be released. Follow the smoke to heaven! With this ceremony you can let go and your wish will come true! The time is now!”

She continued to shake her head. She cried out that he couldn’t let go. I was still bent forward, holding her. “Don’t be afraid!” I called. “You have courage! You know courage! Use that courage now to let go of this woman. Let go and go to heaven at last!”

Now, I can’t say how long this went on. Then, it seemed timeless, the two (or three) of us locked in this quasi-embrace, incense smoke and my voice filling the kitchen, her mother nearby, watching us, crying and wringing her hands.

My back hurt from supporting the patient, but I continued until she calmed. Then I signaled to her mother to move the chair forward so I could gently maneuver her into it. I pressed my back against the kitchen wall to ease the pain and continued the chant to Kwan Yin in a softer voice.

Finally the patient looked up at me and smiled. She nodded her head.

“Is he gone?” I asked.

“Yes.” Then she said, “But the others are still here.”

Oh. I hadn’t known that there were others.

I stepped back in front of the altar, threw more incense on the charcoal, resumed the chant in a louder voice, and called out to the lesser spirits, saying that they could follow the boss’s example and go to heaven. I told them this was their chance. Much more quickly this time, she nodded her head and said they were gone. I finished the chant, offering a dedication of gratitude. Then the three of us did three bows to close the ceremony. I passed the figure of Kwan Yin through the remaining incense smoke and gave it to her.

I was exhausted.

The magic I’d brought that day resided in my vow as a priest, in my beautiful Japanese ritual implements, and in my willingness to believe the young woman’s description of her reality. We trusted each other, and it worked. I phoned the social worker from my car to report on our success, and she and I cried together.

The following morning, I spoke to the patient. The spirits were gone, and she and her mother had been able to sleep through the night.

The doctors admitted her to the hospital that day and, to my relief, she was referred to the medical ward for pain control, not to the psych ward for the spirits that had inhabited her.

She died at home two weeks later. The spirits never returned.