The Lords of Form, Speech, and Mind – we think they’ll make us happy and secure, but Carolyn Gimian tells us that everything wrong with the world and our lives is their creation.

The Kalachakra tantra talks about a time when the three lalos, the barbarian kings, will rule the earth. In the 1970’s, Buddhist author Chögyam Trungpa referred to the three lalos as “the Three Lords of Materialism.” That translation has been adopted as the standard, perhaps because it so aptly describes the attitude that rules the modern world. Indeed, materialism is king.

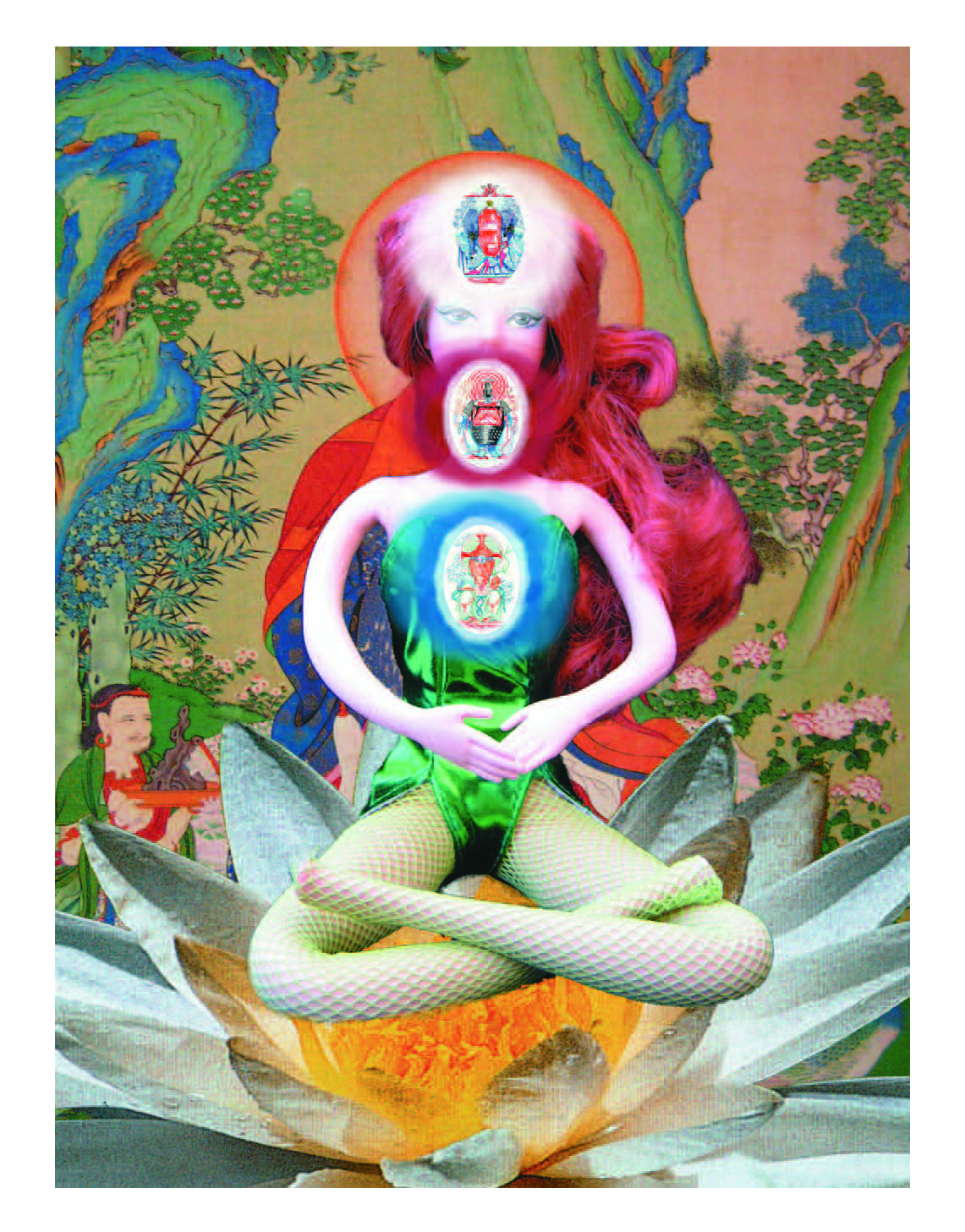

The Three Lords are the Lord of Form, who rules the world of physical materialism; the Lord of Speech, who rules the realm of psychological materialism; and the Lord of Mind, who is the ruler of the world of spiritual materialism.

All Three Lords serve their emperor, ego, who is always busy in the background keeping his nonexistent empire fortified with the ammunition supplied by the Lords. According to the Buddhist understanding, the ego is a collection of rather random heaps of thoughts, feelings, perceptions, and basic strategies for survival that we bundle into a nonexistent whole and label “me.” The Three Lords act in the service of this basic egomania, our deluded attempt to keep this sense of self intact.

On a simple level, these aspects of materialism deal with the challenges of everyday life: fulfilling one’s needs for food and shelter for the body, food for thought, and spiritual sustenance. The problem arises when we begin to pervert these parts of our lives, adopting them as the saving grace or using them to protect us from our basic insecurities.

Why are you unhappy? What is it that you need in life? When you begin to think that the pink pair of shoes you saw last week at the mall is going to really rock your boat and rescue you from depression, that is the moment when the Lord of Form, or physical materialism, begins to hold sway. Think that all your problems will be solved by winning the lottery, writing a bestseller, or being the winning contestant on Survivor? Welcome to the game show of the Lord of Form.

Just about any religion or spiritual movement will tell you that physical materialism is not the ultimate solution. It is an extremely powerful force, especially in the world today, but it is easier to deconstruct than the other two Lords—although not necessarily easy to escape from. Psychological materialism, on the other hand, is much more subtle, and religion is split on whether or not psychology, philosophy, and scientific systems of belief are enemies or friends.

The Lord of Speech rules the realm of our thoughts, our conceptual understanding of ourselves and the world. Why is speech connected with psychological materialism? Because we construct ourselves with words; we present ourselves to the world with speech, whether written or spoken. Your business card tells people who you are, as does your resumé. When you meet somebody, you introduce yourself with your name, and then usually you tell the other person a little bit about yourself. That’s your story.

Behind the story, we are saying “This is me. This is who I am.” Most of the time, most of us want to protect this basic sense of self at all costs. The Three Lords understand this perfectly and that’s how they make their living, so to speak. If the Lord of Form hasn’t convinced you that plain old physical materialism will satisfy you and keep you safe, then the Lord of Speech takes over the sales pitch.

In the Buddhist teachings, intellectual sharpness and understanding are highly prized. Prajna, or discriminating awareness, is thought of as almost a goddess of wisdom. However, using systems of thought to enhance our sense of self and to ward off confusion and insecurity creates a prison for the intellect, and in the end, we stop seeing clearly. We are no longer investigating the world with open eyes; we are just working harder and harder to describe our fantasy world and to solidify it until we think it’s the real thing.

Science has served over the centuries as the handmaiden for the Lord of Speech, yet it has also served as a source of knowledge and investigation that tears down or deconstructs the illusory world of psychological materialism. Witness Copernicus and Galileo. They were huge threats to the egocentric universe, such a deadly threat that in Galileo’s case he had to be branded an enemy of religion, debunked, and put under house arrest. Today, as far as I know, even the most extreme literal-minded religious fanatics accept that the earth revolves around the sun. In those days, it was heresy, a repudiation of who people thought they were and what they thought the meaning of the universe was. We thought God made the world and the whole universe for us, just for us. He made the sun and the moon for us. It all revolved around us.

Charles Darwin is still controversial. Of course, it’s been less than two hundred years since he looked at the evidence of human evolution and suggested that we were related to other animals and that we were a somewhat random occurrence in the universe, governed not by divine providence but by a principle called “survival of the fittest.” We might now accept that the earth revolves around the sun, but on this earth, God created us as his chosen ones.

Or did he? That is still being debated in our schools, our churches, our courts, and most importantly, in our own minds. Sophisticated, educated people might scoff at creationists, but on a fundamental level, we all want to feel that we’re special, and that not just we but “I” have a special place in the universe.

We certainly see ourselves as the center of our individual universe. We seem to be wired that way: our modes of perceiving and interacting in the world bring everything back to what we experience as “central headquarters,” or our ego. And the Lord of Speech is waiting right there to tell us that this view of ourselves is a good thing, a great thing in fact. The Lord of Speech tells us that we should ward off any fundamental threats to our sense of self-importance by keeping our story lines intact and adopting those views of the world that support us, me, I.

Freud was another scientific researcher who threatened our sense of self, by suggesting that the conscious “I” was not nearly as securely in control as we would like to think. He pioneered the use of the term ego to refer to the self, though not necessarily in the same way the term has been adopted by Buddhism in the West.

For Freud, a healthy ego had the ability to adapt to reality and interact with the outside world. But he also talked about something called the id, that out-of-control little beastie that unleashes our instinctual desires onto the world. As well, Freud’s suggestion that even infants are affected by sexual impulses and deep, dark emotions was an unsettling challenge to our persona, the nice but mythical person with whom we would like to identify ourselves. Today psychology has become much more tame and acceptable, and we often use therapy to help us feel more secure and to cure our malaise. Is this the predominance of sanity or the work of the Lord of Speech? Perhaps it is a little of both.

Religious and spiritual beliefs, when they are used to manufacture a sense of security and meaning, are the stronghold of the Lord of Mind. Sickness, old age, and death are unpleasant, painful facts of life, hard truths we find extremely difficult to deal with or understand. Why do people suffer? Why do they die? We have been asking these questions since we could frame a question at all. Everyone would like to feel that both their life and their death have meaning. The problem is, we don’t find meaning in the living of life itself, so we want reassurance. We want to know that our memory will survive, or our soul will go on, or that there is some greater meaning to our suffering.

Spiritual materialism, the specialty of the Lord of Mind, is the tendency of the ego to appropriate a religious or spiritual path to strengthen, rather than dismantle, our sense of self-importance. Chögyam Trungpa, who popularized this term, often used it to point to the self-congratulatory use of Eastern religions and New Age philosophies, especially in the sixties and seventies in North America. It can, however, refer to the tendency within any religious movement to use spirituality to reinforce rather than to reveal.

We often avoid authentic spiritual engagement that involves humbling ourselves or giving in. A pernicious form of spiritual materialism, orchestrated by the Lord of Mind, is to imitate or ape spiritual experiences, rather than to actually engage them. We get high, we get absorbed in nothingness or the godhead, we have a cathartic religious experience, but all on our own terms. God loves us, the universe loves us, we love ourselves.

Genuine spirituality offers various paths to investigate what we might call the real mysteries of life. It offers the opportunity both to look more deeply into life and to open out further into the world. It offers exploration, it offers communication, it offers investigation. It offers us genuine questions. Spiritual materialism, on the other hand, says: You don’t have to question. Do this and you’ll be fine. Believe this and you’ll be fine. When you die, you’ll be fine.

The Lord of Mind keeps his fortress intact by banishing a sense of humor. Someone has even made a serious psychological discipline or spiritual path out of laughter. Laugh every day. Go ahead. Start now. Keep it up for five minutes. Keep going. Keep laughing. Now you feel better, don’t you? You don’t? You must not have laughed enough. Let’s go back to the technique and start laughing again.

The Lord of Mind makes religion into a deadly serious business. If there are jokes, they are little in-jokes that don’t threaten our worldview but shore it up. In addition to co-opting conventional religions, the Lord of Mind is happy to make meditation, yoga, astral projection, chanting, and channeling into deadly serious matters. A Buddhist minister and his sangha or a swami and his sannyasins can be every bit as pious and self-righteous as a Christian priest and his congregation.

Sometimes the Lords work together. For example, in pre-Nazi Germany, the Lord of Form was helped out by the Lord of Speech, it would appear. The difficult economic times made it difficult for the Lord of Form to hold sway. So the Lord of Speech seems to have gotten in league with Adolf Hitler to construct a system of thought, National Socialism, that allowed many Germans to blame their economic problems on somebody else, a religious minority.

When we can externalize the threats to our self-existence, we feel justified, we feel strong, and we feel ready to kick some butt. This approach tells you who your enemy is, which also makes you feel good, because it assures you that you are not the problem. Karl Marx also employed this approach, although he fingered different bad guys: capitalism and the ruling class. He too used psychological materialism to shore up the realm of physical materialism. Interesting marriage that.

That kind of “us and them” approach is very powerful but very dangerous, because it becomes a rationale for hurting other people, and sometimes for using hideous means to intimidate, torture, or kill them—and all in the name of the good. In this “unholy” alliance, the Lord of Form, the Lord of Speech, and the Lord of Mind all work together to obscure the real threats to our security and to give us simple answers to our sense of fear and malaise. Holy wars and ethnic cleansings are often the extreme results when the Three Lords work together to play the blame game.

Any provocative or new way of thinking is viewed as a threat to be neutralized by the Three Lords of Materialism. Genuine spiritual inquiry can, and properly should be, threatening. Although Buddhism is an ancient religion, it is a relatively new discovery in the West, especially as a practice lineage, so that makes it potentially fresh and revolutionary in this culture. The Three Lords would like to dismantle Buddhism, but if that’s not possible, they will do their best to appropriate it.

These days, the Lord of Form would like to make Buddhism chic. Have you seen the head of Lord Buddha in a gift store as a candle? You can actually burn the Buddha in your home, as an artistic or aesthetic statement, thanks to the Lord of Form. Zen—the Lords got all over Zen in the world of gourmet cuisine and interior decoration. It’s even a way of thinking or talking: “Oh, that’s so Zen.”

This is somehow a little different than saying, “Oh, that’s so Baptist.” In any culture, the Three Lords figure out what you can trivialize and what you can’t. In the West, in general, you can’t trivialize the Judeo-Christian tradition. In the Middle East, you do not lightly show disrespect for Allah.

Several years ago, I saw an ad in the paper for the opening of a “Buddha Bar.” The advertisement showed a large sprawling Buddha in a bathrobe, holding a martini, with part of his big belly exposed. I didn’t see any letters to the editor objecting to this image, nor were there angry Buddhists picketing at the opening of the bar. I don’t think you would get away with a “Jesus Bar” advertised by a leering Christ holding a chalice of wine.

Such caricatures often trivialize a culture, a minority, a way of thinking, or a genuine tradition that is not mainstream. Our stereotypes of the Beat Generation, for example, make us laugh at “Daddy-O,” rather than howling at the universe as Beat poet Allen Ginsberg would have had us do.

When you describe the Three Lords and their territory in any detail, it begins to feel as though there is nothing outside of their domain. That’s exactly what they would like you to believe. You may say, “Why bother to try to get beyond all this? Isn’t this just what we generally call ‘life’? What’s the problem?” Fair enough.

Or perhaps you are be waiting for me to tell you how to get out of this predicament. I’m sorry, but I don’t know. The point is that every person has to work on this for him- or herself. Any “-ism” I try to sell you to solve your problems can just become another static system of belief, another vehicle for the Three Lords of Materialism.

Here’s a hint, however, and perhaps a twist: the solution is not necessarily to give up tradition. It could be, but traditions are the keepers of wisdom as well as confusion. There is that kind of coemergent quality to life altogether. Problem/promise, neurosis/sanity, awake/asleep: they are inextricably bound together. Uncertainty, paradox, conundrum, irony: these confound the Three Lords, because they would like us to be certain about who we are.

Uncertainty: the Three Lords of Materialism don’t know what to do in that space. We don’t know what to do in that space, which is why we usually opt for some form of certainty, some solution, at that point. What good comes from uncertainty?

All the good in the world. The Lords can’t outsmart that empty feeling that comes back, no matter how much you achieve. You may keep going for eons, maybe lifetimes, but eventually, even if you get everything you want, it’s not enough. You can get all the power and material things, you can get all the therapy, you can get all the religion, you can get all the bliss, and eventually it will not be enough. When somebody has reached that conclusion, they might become desperate and kill themselves, which is missing the point, or they might begin to think about something beyond themselves.

Thus, if you decide you want to help others, that is something the Three Lords of Materialism really don’t like. However, if you only sort of want to help others, that might be okay with them. A certain amount of volunteer work is fine, if it looks good on your resumé and you can check off the “help others” box in your brain. This may sound terribly cynical, but truth be told, a lot of helping others is about helping me feel better about myself.

However, even if you are doing good to make yourself feel good, if you keep going with the helping part and you get far enough down the rabbit hole, you may eventually lose the reference point of yourself. For example, Stephen Lewis is the premier activist in the West working on the AIDS crisis in Africa: he’s definitely not in it for himself. Roméo Dallaire, the Canadian general who headed up the U.N. Peacekeeping Force to Rwanda: all he got was nightmares. Schindler saving the Jews in his factory in Nazi Germany: he ruined himself. Gandhi and Martin Luther King: it wasn’t a “me” thing. You don’t have to start with perfect motivation. Young volunteers who are just checking off a box on their resumé might get sidetracked if they go far enough, look far enough. One of them might become the next Stephen Lewis.

The Buddhist tradition, which exposed the Three Lords of Materialism for what they are, presents other clues for how one might transcend materialism and put the kibosh on the Three Lords. The alternative presented in the Buddhist teachings is called taking refuge.

In this case, it is taking refuge from, rather than taking refuge in. The swirling world of samsaric confusion is immensely powerful; it covers every single millimeter and millisecond of our experience. It papers over our mind with thoughts, feelings, emotions, perceptions, beliefs, and convictions. We take refuge in our wardrobe, we take refuge in our sports [sports] car, we take refuge in our B.A., M.A., Ph.D. We take refuge in our psychoanalyst. We take refuge in Astanga yoga, we take refuge in our families, we take refuge in our jobs, we take refuge in our gods, we take refuge, we take refuge, we take refuge.

The Buddha is an example of someone who walked out on this deception. He walked away from the palace. He realized that it wasn’t actually that good to be the king (apologies to Mel Brooks). He walked away from every system of thought and every ascetic setup that was offered to him as an alternative. The closer he got to actually waking up, the heavier was the assault from the Three Lords—which by the way is an important part of their M.O. If you start to get out of this predicament, they will really come at you. The night the Buddha became enlightened, they sent beautiful maidens, every Playboy Bunny in the realm, to seduce him. They sent armies, they sent weapons. They threatened him. They did whatever they could to drag him back into the whole sordid mess.

What did he do? Nothing. That was his ace in the hole. The Three Lords don’t know what to do with nothing. What can you make out of nothing? Who owns it? Nobody. And nobody is what they don’t want you to become. Please. Be somebody. Make something of yourself. Buddha said, No thanks. That’s what made him the Buddha. And if you take refuge in the Buddha, you are taking that as your example of how to live, how you might actually live your life. Does it sound attractive? Probably not. But it might be.

You can still live at home, keep your job, raise a family, even go to church—but it’s not about you. That’s the only thing. It’s not about me either. And that is really what freaks us out. We know at some level that nobody gives a fig about us. When somebody is patting you on the back and telling you how great you were, or are, or will be, most of the time they are doing that so that you will tell them how great they are. The society of mutual backslapping has a big room in the lodge of the Three Lords.

There is such a thing as genuine friendship, appreciation, and communication. In Buddhism, that is what is meant by the sangha: the people who are also, together, on the path of “It’s really not about me.” It’s not that we give up “me” all at once, but if we admit to ourselves and then admit to others that we know that this “all about me” is a big myth, if even for an instant we admit that, then it’s never the same again.

It’s like after you sleep with somebody. It’s never the same. That’s why the secret revelations on the sitcoms about how your best friend slept with your husband before you were married and never told you—that’s why that story is both so funny and so unsettling. It is never the same. And that’s the sangha. When you are being a flaming jerk and your friend, who knows this, gives you “the look,” it deflates you just a little bit. Because you both know. That’s the beginning of sangha. Take refuge in the sangha. Tell the truth. Just a little.

Then what? What are you going to do? Freud was trying to find answers in psychoanalysis, but he ended up with discontent. Einstein was trying to solve the mysteries of the universe and instead he found genuine mystery. That approach is called the path—taking refuge in the dharma, the teachings. Dharma just means “things as they are.” Take refuge in that. Fundamentally, dharma is not dogma; it’s about being willing to look, being willing to see. Like Galileo did. Like Darwin did. Like we all do when we are awestruck by beauty or terror in a moment.

It’s so penetrating because you have let down your guard. It’s terrible, wonderful. It’s real. That is the point of meditation, which is the basis of the path of dharma: it reveals things clearly to you, over and over again in the most ordinary, insubstantial little ways.

The path of meditation is one way to get out of our mess. Start practicing with any motivation you want. Go ahead, meditate to make yourself feel better, and you might find a much bigger world than you bargained for.

There are other ways in other traditions. The Three Lords of Materialism hope that you won’t find any of them, and if you get close, they have some good tricks up their sleeves. In fact, they are making me a big offer, a really good offer, to shut up. And I’m certainly on a first-name basis with the Three Lords. You better believe it. I’m going to yoga next week, I already own those great pink shoes, and the Lords are making me a terrific deal on a condominium and a seminar called “The Secret Teachings of Not about You” in Costa Rica next winter. And it’s going to be good. I really want to get out of Nova Scotia in February. I’m ready to sign on the dotted line.