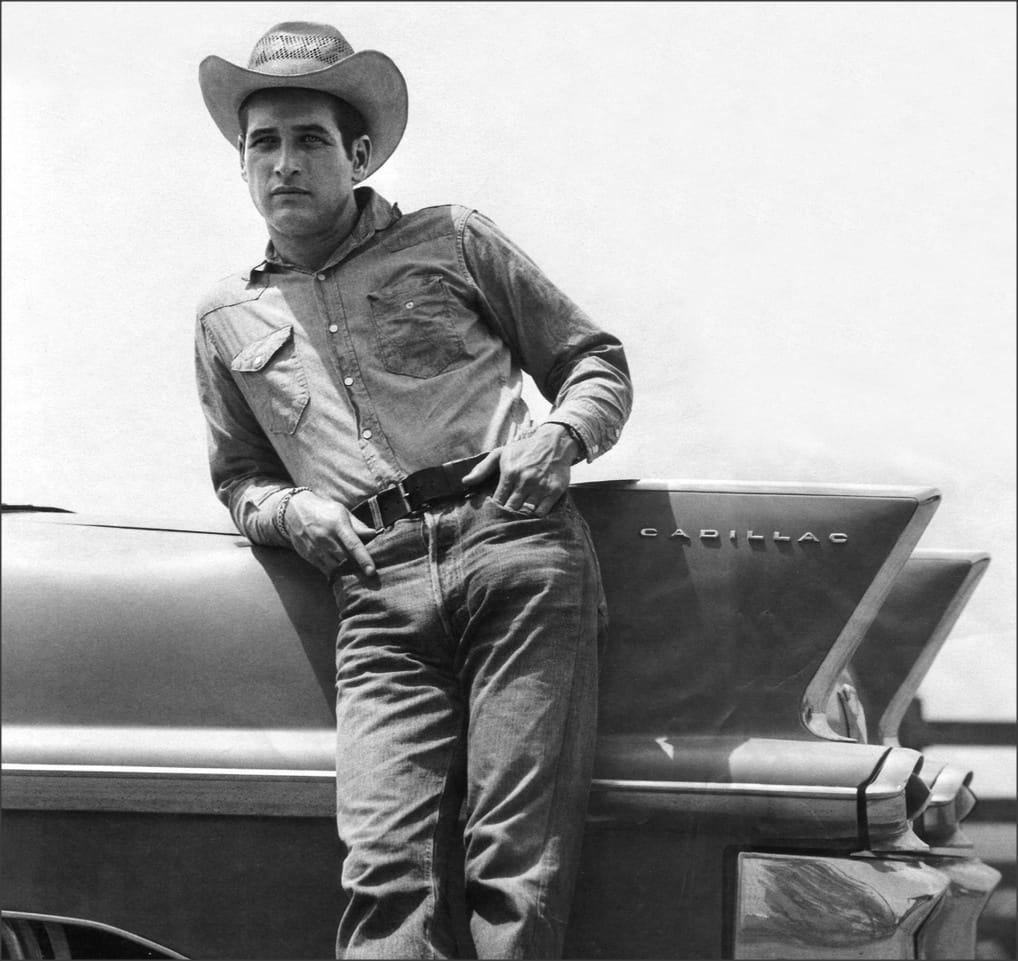

I’d seen Paul Newman around the track. He wore shades, he always had his collar up, and he seemed like the wise, rebellious leader of both his team and the entire paddock. He said good morning to everyone, like a man from a time when men were elegant.

I was twenty at the time, studying philosophy at the University of British Columbia, and depressed. In the summers I ran communications and marketing for a racing-car team owned by a wealthy businessman from Toronto. Through my girlfriend, Laura, I was introduced to Paul at a dinner in Monterey, California. Laura thought I’d be able to find a job with his team.

Our first private conversation was at the Homestead racetrack in Florida. Paul was sitting in an oversized chair in his custom bus, tracing his fingers down the window as raindrops streaked the glass.

“Michael?” He stood up and reached out his hand.

“Good to meet you,” I said.

“Do you bet?”

“Not really,” I answered, looking down at his white socks and running shoes.

“Have a seat,” he said.

There was just a small table between us, and my left knee was almost touching his. He was wearing a Kmart baseball cap and white golf shirt, and it was funny to see someone his age and so admired covered in corporate logos. Feeling like I needed to say something, I stated the obvious: “It’s been raining a lot.”

“How long,” he asked, “do you think it takes for a raindrop to go from the top of the window to the bottom?” His watch was on the table. Maybe he’d been timing the raindrops as he’d been sitting here alone. Maybe he wasn’t alone much. “Pick a raindrop,” he said.

I pointed to one on the window and he pointed to another. My raindrop moved slowly down the tall, tinted window, touched another raindrop, then shot down to the windowsill. Meanwhile, Paul’s thin, old finger traced the path of his raindrop as it dripped slowly down the glass, then crossed the window toward me and finally came to a stop right in front of my knee.

“Again,” he said.

This time I chose a drop at the top of the window. It moved sideways and then stopped. It was absorbed by another droplet and then the whole area pooled, becoming one large drop, which slid down. Paul’s raindrop made a slow, straight line to the bottom of the window, and he looked over at me and smiled.

This went on for another ten minutes. Sometimes I’d look at our reflection in the window, aware that I was sitting with Paul Newman. When that faded I felt ten years old, playing Paul’s rain game. I wondered if he’d done this before or if he was inventing the game as we went along. He didn’t seem eighty.

Paul reached a part of me that had nothing to do with trying to present a face. It was like he was interested in whatever was happening but didn’t need or expect anything. Though I’d come to him about a job, there was more going on.

Paul and I sat undisturbed for an hour. He told me about a script he’d just read that was going to be released as a film. It was about an elderly man who needs a change, so he takes his lawn tractor and drives it across the country.

“A road trip on a lawn tractor,” Paul said. “What do you think?”

“Sounds slow going. Reminds me of the documentaries where filmmakers go up in ultralight aircrafts and migrate with birds.” “No, this is much slower than that.”

As we talked, race cars were being wheeled out to the track. The rain let up.

“Do you smoke cigars?” Paul asked.

“No.”

“Carl, my business partner, smokes.”

“I’ll have a cigarette from time to time,” I said, “but I don’t actually know how to smoke a cigar.”

“I’ll show you.”

Paul stood up and reached for a box in an overhead compartment. His pants were khaki and they kept slipping. He had no belt on. He brought the box down onto the table and opened it. “Carl has a good stash of these.” The front door of the bus opened and a woman came up the stairs. I knew right away it was Paul’s wife, Joanne Woodward. She saw the cigars on the table and shrugged. Paul smiled. She reached out her hand to introduce herself and as I started to stand, she stepped back to allow me to stand all the way. They were a couple from another generation: men opened doors for women, you always stood when you greeted someone, you looked the person you were speaking to direcdy in the eyes, and kindness counted for everything.

“How do you know Laura?” Paul asked me.

“I’ve been dating her.”

“I don’t know her so well, but her brother wants to be an Indy car driver.” “Do you think he’ll get to that level?” I asked.

“Do you think the rain will hold out?”

“I’m not sure.”

Joanne made herself tea in the kitchenette behind us. In her presence, Paul was less enthusiastic about smoking. He put the cigar box under the table.

“Are you going to be in Miami next month?” he asked.

“For the race there, you mean?”

“Yes. Let’s talk more then.”

Paul stood up and smiled with his eyes. I imagined he wanted time alone with Joanne. My body didn’t want to leave.

“One more thing,” he said. “Are you reading anything?”

“I’m reading Joseph Campbell a lot.”

Paul bowed his head, or maybe it was a nod, and I left.

When I started working for Paul, I wore shirts with corporate sponsors, like him. But unlike him, it wore away at my heart.

Every night after I’d come back from the track or meetings with potential business associates, I’d practice yoga or set up the pillows of my hotel bed so I could meditate. One night I read Joseph Campbell’s interviews with Bill Moyers. Campbell said that in his younger years he had a crisis and decided there was only one thing for him to do: he went to the woods to read for five years. I couldn’t stop thinking about that.

A week later, in Monterey, California, Laura and I pulled into her driveway, not far from the famous Pebble Beach Golf Course. I paced Laura’s Spanish house all night while she slept. A voice was telling me that I had to walk out of this life I was creating. The thought was terrifying, but I knew I needed to follow the voice that said: find out what’s really true.

The next morning I woke up on a leather couch as the sun was rising. I was still wearing my nice shirt from dinner the night before and I could feel stubble growing on my chin. Laura was asleep. I’d left my suit coat in her room but I decided not to get it. I called a taxi, drove to the airport, and took the first flight to Michigan, where I had an apartment I rarely visited. In the apartment, I put my toothbrush into a bag with books and a small singing bowl I used for meditation practice and got into my jeep. It was late February and I drove two snowy miles to see Paul Newman, who was visiting the Indy car offices for meetings.

When I walked in, he looked up with concern.

“You look terrible.”

“I haven’t slept.”

“You’re pale.”

“You’re pale too,” I said.

“Are you okay?” He gestured for me to sit down, his hands steady. I sat, and he held my gaze.

“Have you ever read Joseph Campbell?” I said.

“Yes,” he answered. “As a matter of fact, I know Bill Moyers.”

“Well, I’ve been reading their interview and at one point, Campbell says to Moyers, ‘I went to the woods and read for five years.’”

“I can see where you’re going with this,” he said, squinting.

“I need to leave this job.”

He didn’t say anything. We just sat there in the stark white office. I studied his face, and he studied mine. My stomach was a knot. Why was doing the right thing so uncomfortable?

“You know Sandy?” he said, looking toward the office door. Sandy was his secretary.

“Yeah, I know Sandy.”

“She always wanted to be an anthropologist. She’s great to have in the office. She’s kind to everyone who works here, but some days I can see that given different circumstances, she’d have been a great anthropologist.”

I studied my own hands.

“Do you know Dave?”

“Do you mean the one who works as the engineer on Andretti’s car?”

“Yes.”

“He’s a brilliant mathematician. His dream is to teach kids. Michael, what do you want to do?”

My eyes welled up.

“I want to go to the woods and read for five years. I want to learn how to sit still. I want to hear less of my father’s harsh voice in my head all the time.”

“That’s what you should do. You’re so young.”

“I once asked your wife if you had a spiritual practice,” I said. “She told me that when you’re at home in Connecticut, you jump in the river behind your house. She thinks that’s what keeps your spiritual life alive. I don’t know what keeps my life alive.”

“It’s almost March first,” Paul said, opening a drawer on his left. “I’m going to pay you for the rest of the year. Where will you go?”

“When I was a kid, I spent a lot of time in Algonquin Park, just north of Toronto. I think I’ll go there.”

“You should go.”

I turned onto the salty highway. In Toronto, I traded my jeep for an old Volkswagen van. Then two days later, I found an empty gravel road in Algonquin

Park at the edge of a frozen lake. I parked the van and walked into the forest, fell to my knees, and rested my forehead on the frozen earth. I told myself that I’d stay here in this vast forest until I could sit still.

Why can’t human beings sit still? We sit down, but the momentum in our bodies is still racing, scared. I wanted to know what was underneath that. I wanted to know what was underneath my thinking.

When I was ten years old, I swam in South Tea Lake in Algonquin Park. I dove into the cool lake and when I came through the surface and opened my eyes, I was staring into the eyes of a loon. We’d both surfaced at exactly the same time. We were face-to-face. In the background there was sky and forest, and in the loon’s eyes there was black and gold. Then the loon ducked its beak straight down and disappeared into the black lake.

Now I was in Algonquin Park again, in the middle of winter. I slept in the van during the day because I was scared of freezing at night. When the sun disappeared into the trees I’d practice sitting meditation, then I’d walk through the trees in the dark. In March, the sound of cracking ice on the frozen lakes is exactly like thunder. I listened to that thunder day in and day out for two months. Paul Newman’s beautiful eyes and the eyes of that loon were all mixed up with each other. I was learning to sit still.

I stayed in Algonquin Park for eight months and didn’t speak with my family or friends for an entire year. I wrote postcards to Paul but never sent them. I put his photo next to the little Buddha I had on the dashboard.

The nights were lit by a dry moon, hanging up there over the frozen bogs, and I was oblivious then to what the wild was doing to me. I wondered if there was a way of going through loneliness to a sense of being alone without feeling alone.

There are things you can’t think your way into.

After eight months in the park I returned to Toronto, got a job at a bakery, and started studying yoga and Buddhism more formally. Paul and I never spoke again.