“A lot of time here is spent in great tranquility and peace,” says executive director Andrew Olendzki. “We get inspired by words and concepts and perceptions and ideas, and then we allow plenty of time and space to let go of that mode of mind and just be more open and relaxed and slower.”

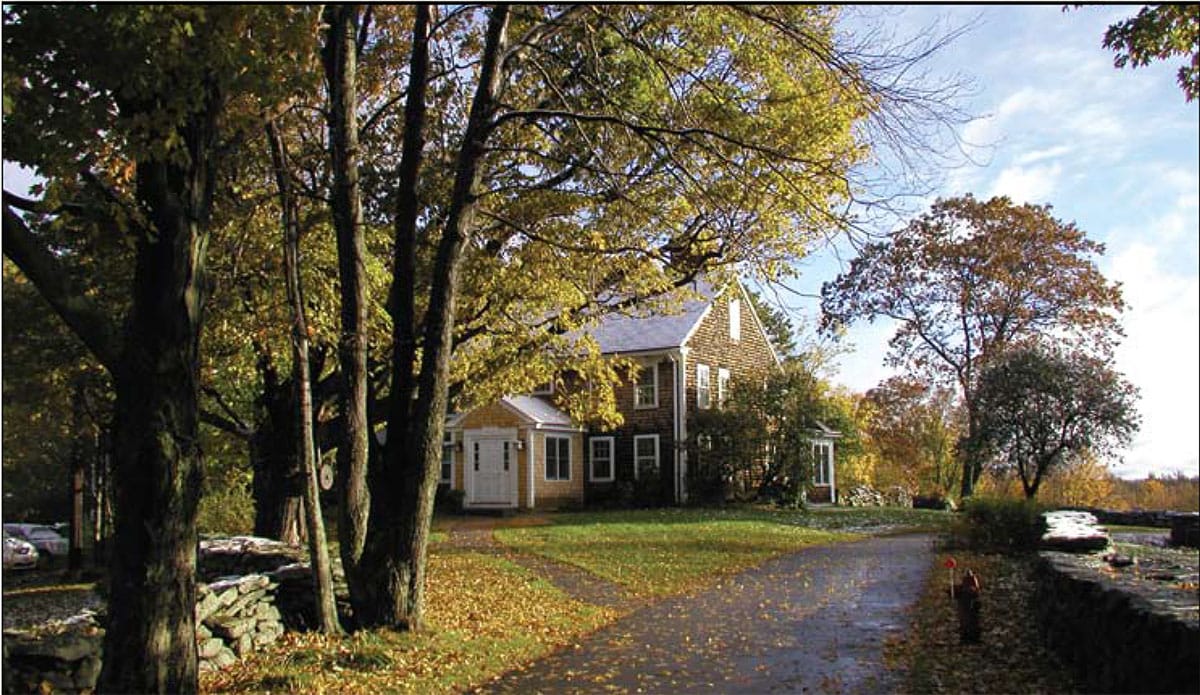

The Barre Center (BCBS) is located on 90 acres of forest in central Massachusetts, just a stone’s throw from the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) retreat center. It was founded in 1989 as a complement to IMS and operates as a separate organization.

The center is small, and plans to stay that way; only about a thousand people a year attend its programs. The center’s focus is on making sure that the students who come here have a deep experience that can improve their lives. Students carefully consider the teachings at the heart of Buddhist traditions, and through discussion and contemplation they work to bring the teachings into their lives.

“It was recognized that for meditation practice to thrive over the long term in this country, it needs to be informed and supported by the deep, classical tradition,” Olendzki says. “We benefit from studying the tradition and bringing the teachings into dialogue with contemporary ideas.

“Those things are discouraged at a retreat center. In order to promote investigation and integration, without impinging on the purity of the meditation center, we needed something different but parallel. So the study center was born as an offshoot of IMS.”

There are two full-time staff members. Olendzki, a former executive director of IMS, was trained in Buddhist studies in England and Sri Lanka, as well as at Harvard. The resident scholar is Mu Soeng, an author and former monk trained in the Korean Zen tradition.

“This is a crossroads of the Buddhist world,” Mu Soeng says. “In the middle of nowhere, in a town no one has heard of, there are all these Buddhist activities going on. I think of medieval Italian cities in the 11th or 12th centuries, which became centers of learning.”

Mu Soeng spends much of his time researching and writing, and he teaches too. He also attends some of the programs led by visiting teachers; in the upcoming year these will include Essentials of Buddhist Psychology, Bringing Wisdom to the Brahmaviharas, and Personal and Social Transformation: Exploring Interdependence.

Most of the students are serious practitioners looking to deepen their understanding of Buddhist texts or their practice, or both. “Everyone comes here because they have some personal interest, some desire for personal transformation,” Olendzki says. “They are looking at the material from a perspective of how it resonates with their own experience, how it contributes to their own growth. So there’s a kind of integrity and seriousness about the level of investigation.”

Olendzki says the center has characteristics similar to—but still different from—a college, a retreat center, and a monastery. It is dedicated to study; yet unlike a college, it is quiet. There are statues of the Buddha, though unlike many meditation retreats it has no shrine room. While dedicated to deepening students’ experience, the center also has a “secular feel.”

A remarkable 38 teachers act as visiting faculty, and almost all will teach in 2008. Some have practiced as monks or nuns, many are university professors or psychotherapists, and most are authors. They combine to create a program lineup that is both broad and deep.

Upcoming offerings include Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara, a Soto Zen priest and abbot of the Village Zendo in Manhattan, discussing the Heart Sutra. Margo McLouglin, a graduate of the Harvard Divinity School and a translator, will explore the Jatakas as both literature and a tool for awakening. Ordained priests in the Shin Buddhist tradition, Taitetsu Unno and Mark Unno, are scheduled to teach a class on the philosophical and cultural dimensions of Shin Buddhism. And four health professionals, including Jack Engler, who teaches psychotherapy trainees at Harvard Medical School, will host an intensive mindfulness retreat for mental health professionals.

Courses can be as short as a day or a weekend, or up to a week long. As well, BCBS offers a number of long-term programs. There is a yearlong integrated study and practice program—including four five-day study retreats—in which students explore the relationship of the teachings to meditation practice. An independent study program is also available to scholars and other students.

The Bhavana Program, which runs five or seven days, is especially popular. It integrates daily morning periods of studying texts into an otherwise silent retreat of sitting and walking meditation. After reading a brief text each morning, students are encouraged to consider it carefully and talk about how it relates to their own experience.

“It provides a contemplative space for the teachings to sink in,” Olendzki says, “and also to have mediation practice be guided and directed by some of the classical teachings of the historical Buddha. By and large, people have found the combination very valuable.”

The BCBS mission calls for the exploration of all schools of Buddhism and also dialogue with other religious and scientific traditions. Past events have included Buddhist-Christian dialogues, Buddhist-Jewish dialogues, a vipassana retreat for rabbis, and discussions with a variety of scientists.

In every course, Olendzki says, a community develops. After spending a week in the woods, talking together, eating meals together, “There is a real sense of getting inspired by others, of learning from each other. It’s less introspective or individual than a retreat center.”

The students’ appreciation is reflected in their giving: one-quarter of the BCBS’s annual $400,000 budget comes from donations. Last year it launched a three-year capital campaign to raise $2 million, money that will be used to increase the size of the library, add a classroom so the original hall is used for meditation only, and create five new rooms for students to sleep in.

“We do what we do very modestly, very quietly,” Olendzki says. “We’re not really trying to reach out to a whole lot of people, or play numbers games, or income games, or celebrity games. We’re just trying to do what we do, with as much integrity as possible. It’s a small contribution, but there’s a ripple effect.”