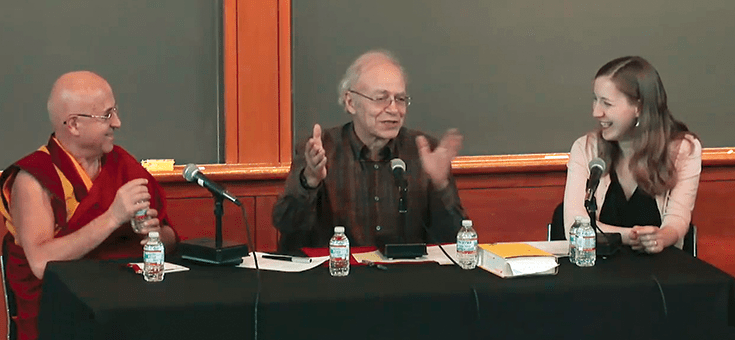

Peter Singer: Matthieu, how did you come to be known as the “happiest man in the world”? What is it like to walk around with that burden? [Laughter]

Matthieu Ricard: We were studying the effect on the brain of meditating on compassion and altruistic love, and we saw that it powerfully activated certain areas of my brain, in gamma frequency especially.

Then several years later, I got a midnight call in Nepal that the BBC wanted to talk to me, because an article in the Independent said that they’d found the happiest person in the world—who was me.

I got on the line and said, “Well, anyone can be the happiest man or woman in the world—if you look for happiness in the right place.” I made all these disclaimers, but from then on it was out of control. The “happiest man” idea still pops up every few years.

Finally, a Tibetan friend of mine said, “Just use it for a good purpose. It’s better than being called the unhappiest person in the world!” [Laughter] But there’s clearly no scientific basis for it—there’s no happiness center in the brain as such.

Peter Singer: So, what is happiness?

Matthieu Ricard: One misunderstanding is that it’s an endless succession of pleasant experiences. That seems more like a recipe for exhaustion than anything else. [Laughter]

Happiness is a cluster of the fundamental human qualities, and altruism is one of the key ones. This kind of happiness is a way of being, and the more you experience it, the more it deepens. You can cultivate it.

Pleasure is something that changes all the time. You can listen to the most beautiful music, but twenty-four nonstop hours of it can be torture. You can also feel great pleasure even if everyone is suffering around you.

I think happiness is basically a cluster of the fundamental human qualities. Altruism is one of the key ones, and also inner strength, inner freedom, resilience. This kind of happiness is a way of being, and the more you experience it, the more it deepens. You can cultivate it.

Peter Singer: In your book you argue that altruism is the path to happiness, rather than consuming material goods, and there’s good research on that. In one study, students were randomly selected and given money. Half were told to do something good for others, and half were told to spend it on having a good time. At the end of the day, the first group had enjoyed their day more. That’s just one of many such studies. Why is it, then, that most of us pursue happiness through consumption rather than altruism?

Matthieu Ricard: We tie our hopes and fears to outer conditions: “If I have all that, then I will be happy.” The common idea is that if you have everything, you’ll be happy. You must have to be happy. This idea shows our vulnerability, because our control of outer conditions is very limited. If one ingredient is missing, the whole thing collapses.

Of course, we need to work on some outer conditions. We should take people out of poverty, work for social justice, and remedy as much as we can any form of suffering, whether among humans or animals.

Peter Singer: You are involved in a lot of humanitarian work, but it is sometimes thought that Buddhism involves an inward retreat. In your book, you describe the scientific research on people who have meditated for 20,000, 30,000, or even 60,000 hours, in one case.

I did a little calculation: 60,000 hours of meditation means meditating eight hours a day, every day, for twenty years. If you’re interested in reducing suffering in the world, can you justify spending twenty years full-time on training your mind, rather than getting out into the world to make a positive difference?

Matthieu Ricard: I’ve heard that argument quite a few times: “Oh, isn’t it selfish to go to a hermitage for months and months?” But if one of the goals of our training is to get rid of selfishness, you can’t say it’s a selfish pursuit. If your goal is to help others, you need to build up the inner resources and strength to do that.

I’ve been asked, do you have any regrets in life? I say, not when I’ve put compassion in action. There’s a saying in Buddhism that something that does not benefit others isn’t worth doing. I think it’s a good criterion.

Peter Singer: Julia, you have come at altruism from a different direction. You and your husband, Jeff Kaufman, give away an unusually large amount of your income. How did you come to practice altruism in this way?

Julia Wise: I was quite aware of people who lacked basic things that I think are pretty important to happiness. We’ve said here that most material things are not important, but when you are lacking basic material things, it really does matter.

At the same time, I recognized I had advantages that most people don’t—being born in the United States, being born to a family that could provide me with things that I needed, being healthy.

So I was coming from a place of trying to even things out some. Some of us are born luckier than others in ways. And things continue happening throughout life that advantage some people and disadvantage others.

Peter Singer: How did you and Jeff decide how much to give?

Julia Wise: As a younger person, I wanted to aim high—giving away as much as possible and living on as little as possible. My husband was coming at it from a bit more conservative viewpoint, so we ended up sort of averaging it.

Peter Singer: The average between 100% and 0%, I should say. [Laughter]

Julia Wise: Yeah—we give 50%, and we’ve been doing that for several years now. We’ve worked up to it gradually since our first jobs out of college, and we find that it works well for us. Fifty percent of what we earn is still plenty for us.

Peter Singer: How do you decide how much you’re going to give or pass on to your children, and what you’ll give strangers?

Julia Wise: Like most parents, we want to give our children the things they actually need to develop fully as people. But we don’t want to give them extra stuff that will spoil them or create unrealistic expectations. Half of what we earn is still plenty, especially by world standards. Certainly it’s much more than most people have, and most people are raising children on a lot less than we have, even after donating. So we don’t expect that our children will be deprived.

We also think about what other parents go through when they don’t have enough for their children’s basic needs. A lot of the interventions we support are targeted at children, like mosquito nets to prevent malaria or deworming treatments to treat children infected with parasites. These are effective causes, and it means a lot to me that I’m able to help keep other parents from watching their children suffer, which must be incredibly painful for parent and child alike.

Peter Singer: Matthieu, if people say, “I want to be happy, so I’m going to be an altruist,” are they really being altruistic?

What people call the ‘warm glow’ comes from doing good things for others. The idea that an action can only be altruistic if it is a painful sacrifice is silly. There is a natural joy in being truly altruistic.

Matthieu Ricard: No, of course not, and it will not work.

What people call the “warm glow,” the positive feeling that comes from doing good things for others, does not originate from just doing something that benefits others. It comes from doing it with a warm heart. So the pursuit of selfish happiness is bound to fail. To be preoccupied with “me, me, me” all day long makes you feel miserable, and you will make everyone’s life miserable around you.

Peter Singer: And if people do get a warm glow from knowing they’ve helped others, then those are the kind of people we want in the world, right?

Matthieu Ricard: What makes the warm glow not selfish is that it comes as a secondary effect from truly helping others. Suppose you cultivate a wheat field to feed your village or family. You cultivate wheat and get straw as a bonus. The warm glow comes from a sincere good heart. Let’s say you don’t give a damn about poor people, but you’ve heard giving would make you feel good. So you give, but you don’t feel the warm glow.

In Altruism in Humans, Daniel Batson defines altruism as an intention, a motivation. That doesn’t mean that we are altruistic all the time, but at some point there will be the intention, unambiguously, that you want to do good for others. Maybe you’ll get the warm glow, but that’s not your primary motive. But the idea that an action can only be altruistic if you perceive it as a painful sacrifice is also very silly. There is a natural joy in being truly altruistic.

Peter Singer: Your book discusses voluntary simplicity. How do you understand the concept?

Matthieu Ricard: Peter, your own recent book referenced a study that said three-quarters of the people in Los Angeles can’t fit their car in their garage because they have too much stuff. Voluntary simplicity is happy simplicity, because piling up goods doesn’t necessarily make us happy. We have to take care of our stuff, we have to fix it, and so on.

The idea behind voluntary simplicity is that a simple life is a happy life. I’ll give you one example. I was at the hermitage office, back in the Himalayas. There’s no heating in the winter and the electricity goes on and off, but I cannot find a happier place to be. I was thinking, okay, imagine a fairy comes and offers me three material wishes. What am I going to wish for? And I started laughing. There was not a single material thing I could think of that would improve what I had there. That’s happy voluntary simplicity. Another aspect of voluntary simplicity is that, as a monk, I don’t have many personal needs—I do not own a house, land, a car—and therefore it is easy for me to dedicate to helping others 95% of any financial resources that come my way.

Julia Wise: Family and friendship are more important to one’s happiness than things like material wealth. We live near my husband’s family so that our daughter can spend time with her aunts and her grandfather. We structure our time to emphasize those relationships more than working extra hours to bring in more income to buy more things.

I’m watching my sister plan her wedding right now—it takes like a year and a half to plan a wedding! I asked my parents if it was like that when they got married, and they said, no, there wasn’t the same expectation that everything had to be so elaborate.

Now, is all this bringing you closer to your partner? Is it bringing you closer to your friends, who now need to cram into their bridesmaid dresses? How is this enriching your life? I don’t know!

Peter Singer: Let’s talk about the roles of the head and heart. How does the cognitive or reasoning element combine with the emotional?

Matthieu Ricard: Many psychologists and neuroscientists see empathy in two ways: cognitive and emotional empathy. Cognitive empathy is our ability to imagine someone else’s situation and perspective cognitively, but it doesn’t necessarily lead to altruistic behavior. Some people say that altruism has to be defined by action—if there’s no action, it’s not altruistic. But there are beneficial actions that can be motivated by selfish motivations. Also, you can have a great intention to do good but for some reason, the circumstances do not allow you to put that intention into action. That doesn’t negate the fact that it was altruistic.

Emotional empathy is affective resonance: when you see someone with a big smile and you feel joyful. And if you see a person suffering, you suffer because of it.

The problem with emotional empathy alone—without the bigger dimension of, say, compassion and warmheartedness—is that you may soon burn out. Suppose you are a nurse. Day after day after day, you keep on resonating with the suffering you see. It leads to burnout. Altruism offers an antidote.

I saw this myself when I was working with the neuroscientist Tania Singer. Tania put me in an fMRI scanner and said, “Do your usual meditation,” which in my case was compassion meditation. After ten minutes she asked, “What are you doing? This is not what we normally see in the brain when people are experiencing empathy.” I explained that compassion is quite different from empathy, so she said, “Well, could you do just empathy now?”

I’d been in an area of Tibet that had experienced a major earthquake, and I’d recently seen a documentary about Romanian orphans. For an hour, I tried to resonate again and again with these terrible images. It was complete burnout.

When Tania asked me if I would like to return to my compassion meditation, I said, “Please! I can’t stand this feeling anymore.” The altruistic love and compassion meditation I then did was so different. I felt a stream of love going out to those children, embracing them. The fMRI showed that the effect on the brain was very different, too.

Peter Singer: Evolutionary theory can easily explain altruism toward kin, toward people we’re in a reciprocal relationship with, but it has more difficulty explaining altruism toward strangers.

Matthieu Ricard: We have this faculty for caring and valuing others, which I think comes to us from evolution. The question is, how can we extend that?

It’s natural to think, “I don’t want to suffer. My children don’t want to suffer.” But what about other children, other sentient beings? We know they don’t want to suffer either, and they’re trying to achieve happiness in their own ways.

Buddhism says we should extend our concern to all sentient beings. But it’s not about some abstract, infinite number of beings. It’sthe attitude that you will relate in a benevolent way to anyone who comes into the field of your attention.

Why shouldn’t we be concerned about them? Where does our concern stop? At our own child? Why not other children? All these barriers start making less and less sense: “I can feel benevolence toward all sentient beings—except those fifteen guys I can’t stand.”

Buddhism says we should extend our concern to all sentient beings. Some people say that feels sort of vague. It’s not like the child who’s right in front of you. How can you really feel altruism for some abstract, infinite number of beings? But it’s not about that. It’s more like a disposition or attitude that, a priori, you will relate in a benevolent way to anyone who comes into the field of your attention. That’s the way to extend your concern outward.

Peter Singer: Can we use meditation to train ourselves to be more altruistic and extend our compassion?

Matthieu Ricard: Maybe meditation needs to be demystified a bit first. Usually you’ll hear clichés about meditation, like “Oh, you have to empty your mind and relax.” If you try to empty your mind, it’s not going to work.

If you look at the Sanskrit and Tibetan words that are usually translated as “meditation,” they indicate a process of cultivating, or becoming more familiar with, something. What surprises me is that we acknowledge the need for training in most skills, from reading and writing to playing chess or piano. But when it comes to our basic human qualities, we think, “Well, that’s just the way I am. I have to love my defects as much as my qualities.” As if we could do nothing about who we are. We have the potential to cultivate focused attention, emotional balance, altruism, and compassion. The great discovery of neuroplasticity is that through exposure to novel experiences and training, you can change. That’s what practicing meditation does.