Shunryu Suzuki Roshi has had an enormous influence on the growth of buddhadharma in the West. Yet when he came to San Francisco in 1959, he had no plans, no grand strategy—only a bottomless confidence in the power of the dharma. He sat zazen every morning in his temple, alone, until gradually some American students began to join him.

It all grew from there: the San Francisco Zen Center, Tassajara monastery, the publication of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, many ordained disciples, scores of lay disciples, thousands of followers. But Suzuki Roshi did not like us making something special out of who he was. “Nothing special” was his credo. When the Japanese Soto sect sent him a yellow robe—a high honor—he would not wear it. The credit, to his mind, belonged not to him, but to the dharma itself, and to us. In the end, what he cared about was us.

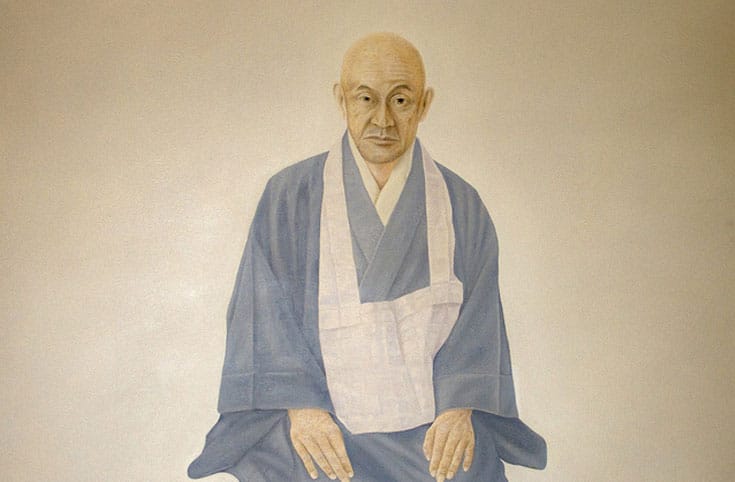

He felt to us like an ancient being from another time and place. And yet he was of the modern world too.

His life straddled the ancient and modern worlds. Born in Japan in 1904, the son of a Zen priest, he was trained by the best teachers of his generation. He felt to us like an ancient being from another time and place. And yet he was of the modern world too. He had a wife and family; he had lived through World War II as a temple priest in Japan. It is said that in Japan he was strict and short of temper. Yet to us he was generous, lighthearted and patient.

In those early days, after zazen we would file past him and bow to him, one by one, while he bowed back. To look into his face each morning was an important moment. Ed Brown, a fellow disciple, described it this way: “His face was impassive, with no trace of liking or disliking, approving or disapproving . . . I had never met anyone like that—someone who seemed so completely present and receptive, yet unmoved on the surface, as though events reverberated and disappeared into some vast space. I felt grateful and privileged.” Was this the face of enlightenment?

In the preface to Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Suzuki Roshi says, “It’s not that satori is unimportant, but it’s not the part of Zen that needs to be stressed.” It is easy to misunderstand such a statement. Once I came to him in private and announced, “I’m here to attain enlightenment.” He quietly looked me in the eye for a moment, and replied, “If your practice is good, enlightenment will come. But even if it doesn’t, it is almost the same.” I’ve been chewing on that statement for over thirty years, and still I haven’t exhausted it. A whole universe of teaching can unfold from that “almost.” And yet equally important for me was the way he looked at me even before he spoke. What Suzuki Roshi constantly talked about was how not to be “caught” by enlightenment, how not to make it into something special, a possession, a “conceit.” The phrase people most associate with him—”beginner’s mind”—means something like this. It is not a beginner’s teaching.

Suzuki Roshi used all the traditional teaching devices—koans, scriptures, Zen writings, occasionally gesturing or shouting—but his preferred mode was to interact with us in the arena of ordinary activity. Each of us has our stories. One day I was the attendant serving tea to Suzuki Roshi and a visiting Zen teacher. I served them and myself the tea, along with some olives that someone had given Suzuki Roshi as a gift. The two masters chatted, paying me no mind. And then, without looking at me or interrupting what he was saying, Suzuki Roshi reached over, plucked an olive pit from my plate, popped it in his mouth, and began sucking on it. What was he doing? I realized then that I hadn’t completely eaten my olive; there was still a bit of meat on the pit. When he casually replaced the pit on my plate, it was completely clean. I can’t describe how I felt—it was like swallowing an iron ball. That olive pit is still teaching me today.

When Suzuki Roshi became terminally ill with cancer, our whole world seemed to collapse. But not his. Even though his skin was gradually turning green, he talked and acted as if nothing special was going on. Those who were attending him noticed that he was in great pain, but he wouldn’t take any medication for it. Instead he hobbled about in the halls, joking about his illness, making light of it, apologizing for being a “lazy monk” by not getting up for zazen.

He declined more rapidly than anyone expected. In the early morning of the first day of rohatsu sesshin, the traditional seven-day retreat at the beginning of December, I was sitting by the door, in charge of ringing the bell, when the door opened and Suzuki Roshi’s wife appeared. “Get Baker Roshi!” she whispered loudly, meaning Richard Baker, the disciple that Suzuki Roshi had appointed to succeed him. I jumped in shock. “Hai!” I whispered back equally loudly. I knew what was happening. Within the hour all of us were lined up on the stairs, waiting for our turn to make our final bows to our teacher’s corpse.

He was the embodiment of his own best teaching: Don’t stick to anything, even the truth. Each moment new.

I don’t know how he arranged to die at the exact moment he did, so considerately, giving us seven days on our cushion to sit with it, to absorb it. Days later, at the crematorium, as his coffin was being wheeled to the oven, I cried and cried. I felt that I would never see his like on this earth again. I realized only then how much I loved him, not just as a teacher, but as a human being who had given his all to us. Since then he has often come to me in my dreams, usually not saying anything, just looking. Checking up on me, I suppose.

How could Suzuki Roshi be so calm and ordinary in the face of death? I often wondered about this in the months after his death. What gave him that power? Why didn’t he grieve, if not for himself, then for his work—all that he had created in America, everything that he worked his whole life to bring about? The answer is clear. He was always ready to die. He was the embodiment of his own best teaching: Don’t stick to anything, even the truth. Each moment new. That was his dharma.

And it continues. There are many teachers now in the Shunryu lineage, including many who never knew Suzuki Roshi personally. Every so often, one of them will nod or speak, and I will see or hear Suzuki Roshi in their gesture. What can we say about this?

It continues.