A white marble statue of the Buddha, a crack across its smooth face and two fingers of its right hand missing thanks to an encounter with a candle years ago, presides over the fireplace in Robert and Nena Thurman’s charmingly Bohemian home in Woodstock, New York. The statue is special, Nena explains, because when the aforementioned candle toppled over, the statue did, too. And falling just so, so the story goes, it snuffed out the flame and saved their home, which is girded by visible wooden beams, from burning down.

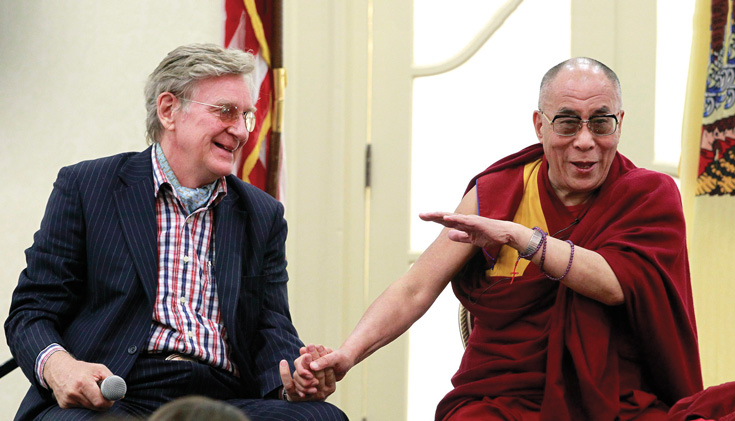

Robert points out another sacred statue in the living room—this one of Songtsen Gampo, the first Buddhist king of Tibet, depicted with a tiny second head on top of his own, to represent his guru. That was a gift from the Dalai Lama, who also happens to be a lifelong “buddy” of Robert’s and the man who in 1965 ordained him as the first American monk in the Tibetan tradition.

Robert gave up monkhood two years later to marry Nena, but has remained close enough to His Holiness, as he often calls him, to joke with him when they’re together. The Dalai Lama once, for instance, referred to Robert as his “ogre,” which Robert explains is “kind of an in-joke among Tibetans about Westerners.” But Robert objected: “You don’t call me your ogre. You call me the king of the ogres!”

To talk with Robert and Nena, who have been married for fifty-one years, is to hear many such stories. Particularly when it comes to the loquacious Robert, every knickknack, every thought, unlocks another thought, another story, each one as interesting, funny, or surprising as the next. It’s this charisma that has made him one of America’s most famous Buddhists and a rock star of a religious studies professor at Columbia University, where he has taught Indo-Tibetan studies for thirty years.

The seventy-six-year-old, whose many books include Why the Dalai Lama Matters and a translation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, is retiring from that storied career next year. But it’s hard to imagine him or Nena—as much his professional and spiritual partner as his wife—slowing down. They’ll still have Tibet House, their cultural center in New York City, and Menla, their Tibet-inspired spa and retreat facility in the Catskills, to keep them busy.

The Thurmans’ abundant energy is apparent even as they do their version of relaxing. In their mountain home, on this sunny spring day, they enjoy goat cheese, rice crackers, and dandelion tea, while they trade reminders about life’s mundanities—picking up the car from the shop, the kids coming to visit—and Robert holds forth. About the future of Buddhism in America: we need more dharma knowledge, belief in past and future lives, and a stronger monastic tradition. About the Tibetan cause: he’s optimistic. And about secular mindfulness meditation centers: he’s cool with them.

Robert Thurman cuts a striking figure with his swath of thick, silver hair perched above his wire-rimmed glasses and blue eyes, the left one a prosthetic replacing the eye he lost in a 1961 accident involving a racecar and a car jack. He’s clear about what his main contribution to Buddhist thought over the past five decades has been: “It’s that meditation will not solve the problem if you don’t learn something.”

In American Buddhism, he says, “the main thing has been to just meditate and it will all be solved. That is a bunch of b.s., as far as I’m concerned. Meditation is essential, but only after learning something. My contribution has been to maintain that, which is less visible than people building these dharma empires facilitated by lobotomizing people’s thinking process, if you want to put it in a negative, critical manner. You do it for years and then you think, ‘Gee whiz, the buzz I got from shutting down my thinking process was not enlightenment.’”

Robert certainly doesn’t mince words. But it follows that a professor would passionately emphasize the dissemination of knowledge, and his contribution to spreading knowledge of the dharma goes beyond established Buddhist practitioners: his popular courses at Columbia have introduced Buddhist philosophy to thousands of students who might never have known about it otherwise.

In the classroom, Robert has maintained an understandably stricter emphasis on learning rather than Buddhist practice. “In academics you can’t proselytize,” he says. “I never sent a single student to a Buddhist center. I was asked many times to suggest a center, but I always replied that I would only give you a rule of thumb, which is you should rely on teachers who are very open to your study. Teachers who don’t just say, ‘This is it, one-stop-shopping. You have karma with me, so don’t go anywhere else.’”

To his colleague Peter Awn, a professor of Islamic studies and chair of Columbia’s department of religion when Thurman was hired, Robert’s combination of intellect and devotion to Buddhism has been the key to his profound impact on students. “That’s not an easy line to walk—the ability to present oneself as rigorously academic, critical as well as positive, but also maintain and have a very public engagement with your own personal commitment,” Awn says. “He has really brought Indo-Tibetan Buddhism to a level of awareness and intellectual engagement among Americans that did not exist before him.”

Robert’s charisma adds to his appeal as a professor, as do his Hollywood connections—one of his four children with Nena is the actress Uma Thurman, and he cofounded Tibet House with Richard Gere. “His undergraduate classes are packed,” Awn says. “He’s a dazzling lecturer.

“When he was first hired, we had people walking around looking for Uma sightings,” Awn remembers. But to Robert’s credit, he’s respected for far more than his glittery connections. “As a snobby academic,” says Awn, “let me say that what’s really impressive is the quality of graduate students he’s trained over the years. He is, philosophically, incredibly sophisticated.”

Robert’s unique backstory has allowed him to be effective as a mainstream Buddhist voice and an impassioned advocate for Tibetans suffering under Chinese rule. But he can also make an intellectual argument for past and future lives, translate the Vimalakirti Sutra into English, give the Dalai Lama a good-natured ribbing, and call in a favor from George Lucas.

Robert’s warm relationship with the Dalai Lama has driven much of his career. It began in the 1960s when Robert’s first guru, New Jersey–based Mongolian lama Geshe Wangyal, introduced them. Versed in the Tibetan language and holding degrees from Harvard, Robert traveled to India to teach English and learn from the Dalai Lama. Geshe Wangyal warned that he believed Robert would never be a lifelong monk, but the Dalai Lama ordained Robert anyway. “He made me a monk, I think, to keep me there,” Robert says.

The relationship was reciprocal: Robert received dharma guidance, and in return offered his own academic knowledge. “Our weekly meetings turned into every three days, to the annoyance of the Dalai Lama’s staff,” Robert remembers. “He downloaded everything from me—my Exeter, Harvard smattering of education. I would make up these Tibetan words for scientific concepts. Back and forth.”

When Robert returned to the States to get his PhD from Harvard, he impulsively named his area of studies “Buddhology” on his thesis form, deciding it was a more inclusive term than “Buddhist studies.” He wasn’t studying Buddhists from afar, as if they were part of a separate and alien culture; he was an expert in Buddhism from within. This would distinguish him among religious studies scholars of his time.

Robert’s resolve grew out of an academic culture resistant to his unique combination of traits: a white American studying and subscribing to Buddhism as a spiritual path. “People wrote letters against me getting jobs in the religious studies community because they thought I should be a Christian,” he says. “You could be a Buddhist if you happened, poor thing, to be born outside of Jesus’s reach in Japan or China. But that you would look like me and have become a heathen, it was apostasy.”

Because of this attitude, Robert also felt pressure within academia to be critical of Buddhism in order to prove his neutrality. Basic misunderstandings of Buddhism flourished. When he started teaching at Amherst College in 1973, he presented a new course he called “Buddhist Ethics” to be included in the course catalog. Fellow faculty members challenged him: “How can you teach Buddhist ethics? For ethics, you have to have a self, and Buddhists don’t have one. They might do good things now and again by accident, but they’re not restraining this terrible self, so they don’t have any ethical system.”

Robert’s star power as an ambassador of Tibetan Buddhism in America began to grow in the late 1980s. He and Nena cofounded Tibet House with Richard Gere and composer Philip Glass in 1986 and he accepted his position at Columbia in 1988. In 1997, Time named Robert one of the twenty-five most influential Americans, calling him “the Billy Graham of American Buddhism.” The magazine cited the “glitziness” of his ambassadorship, but it should be known that he’s no-nonsense and welcoming, despite having a former model as a wife and an Oscar nominee as a daughter.

Nena, in fact, appears to be a grounding force for Robert. He doesn’t regret giving up monasticism—and its celibacy—to marry her. “I learned so much from having a family and from my third main guru, my wife,” he says.

Buddhism forged their relationship and has continued to be its driving force. “If you share spiritual aspiration, that is like a glue in a relationship,” Nena says, her Swedish accent evident. “When we first met, it was the thing that attracted me to Bob. He was so knowledgeable about Buddhist philosophy, and I had all these questions—perennial questions. I had been trying to have answers for years and years. With Bob I suddenly had someone who had answers, who had studied. We could have conversations. I found that the best answers could be found in Buddhist philosophy. It was a homecoming feeling.” Because of that shared spiritual commitment, she says, it seemed natural that they would share their lives and work, and that their work would grow out of Buddhism.

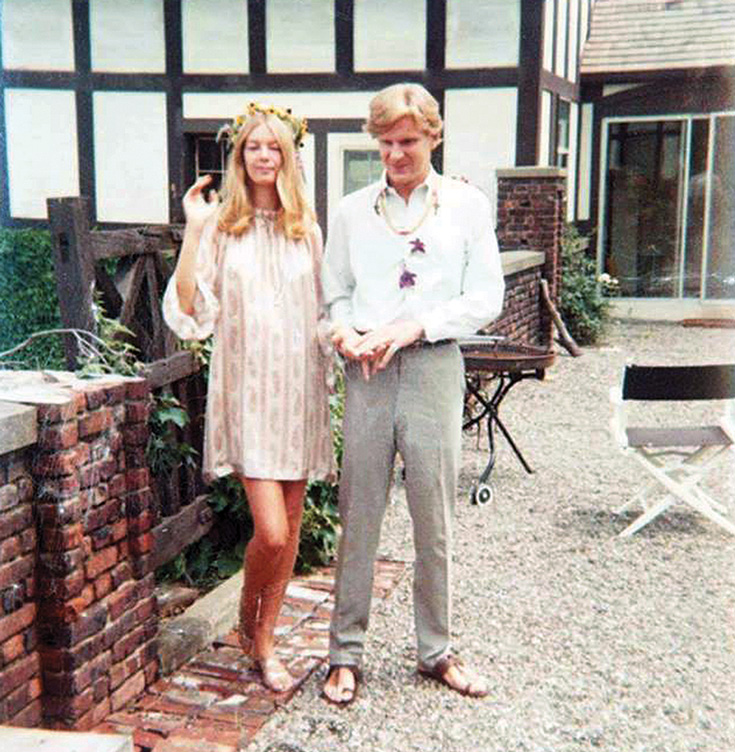

That has materialized at storybook-perfect moments for the couple. They bought the property for their home in Woodstock with seven thousand dollars Nena had inherited in 1968, a year into their marriage—“from a fairy godmother in Europe,” Robert says. They were visiting Woodstock when Robert lost his car keys when he went for a swim. Stuck there for the weekend, they happened upon 9.5 acres for sale that they could afford; aside from the inheritance, they were otherwise “penniless—an ex-monk and an ex-model.” The property became the site of their home for the next five decades and counting.

In 2002, the Catskills region produced another land gift for the Thurmans. During a pilgrimage to sacred Mount Kailash in Tibet, Nena met a woman who was part of a committee that had just purchased a facility in Phoenicia, New York—just twenty minutes from their place in Woodstock. Over time, it had been a hotel, a healing center, and a spiritual retreat, and now the committee was looking to give it to a worthy new cause. The Thurmans and Tibet House became that cause, and Menla was born.

“We always had this idea that it would be great to have a place in the country that would deal more with the medicinal aspects of Buddhism,” says Nena, who now serves as Menla’s managing director. “The facility was a gift from the deities. It was like winning the lottery without buying a ticket.”

The Thurmans’ work with Menla dovetails with their dedication to the Dalai Lama and his homeland. Having spent decades working to free Tibet and preserve Tibetan culture, Robert is surprisingly optimistic about the region’s future. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping—whom Robert refers to as “emperor” because of his extreme power in the Communist country—he believes the country will “go back to classical Chinese culture.” That includes Buddhism.

“Everybody’s sort-of Buddhist in China. So, you’ll have eight hundred million Buddhists there, and out of them, a hundred million will love Tibet and honor it and make a dharma center out of it,” Robert says. “And that will happen, I think, within this Dalai Lama’s lifetime. I think Xi Jinping will make the change in the next year or two. But I don’t know that. We’ve been disappointed before.”

That said, Robert doesn’t believe the Dalai Lama will return to Tibet and stay there like previous Dalai Lamas. “He will of course return when he can, but he’s not just going to stay shut up in Tibet,” Robert says. “He’s serving the world now. I’m sure his successors will be the same.”

As for the future of Buddhism in America, Robert has some more surprising thoughts. He thinks the trend toward boutique meditation centers with no spiritual tradition attached is just fine, despite his admonitions that Buddhist meditators should have knowledge to back up their practice. “Mindfulness meditation centers are not trying to enlist people in a cult,” he says. “They’re just trying to give them a little more awareness. It’s like yoga studios, where people go to meet girls or be athletic, and then they might also go into some of the higher aspects of yoga. I don’t like the purists and their snotty attack, saying, ‘It’s not the real thing.’”

Robert’s most radical idea is his vision for Tibetan Buddhism in the West going forward. For it to truly flourish, he insists that two things must happen: an embrace of rebirth and a strong, celibate, monastic institution.

For starters, Robert says, “The idea of former and future life is essential to the real practice of Buddhism. You have to be scared of where you are going in the next life to have the energy to overcome your deeper instincts. I call it the circuit breaker. Everything is interconnected. If you’re endlessly interconnected, then every little thing counts. If you only get pissed off for one minute and fifty-eight seconds instead of two minutes, those two seconds are big. That’s scary, but it brings you awake.”

And despite having given up his own monasticism for marriage, Robert believes that Tibetan Buddhism needs celibate monastics to grow in the modern West. He once believed that American Buddhism could survive on lay practitioners, but he changed his mind when he studied the U.S. peace movement of the sixties and seventies.

“Seymour Melman gave a speech on the first Earth Day about the nuclear freeze movement,” Robert says. “He said, these marches are great, but you guys have day jobs and you do this in your spare time. The war industry has professional, lifelong careers and zillions of dollars in those careers. How are you really going to match that in the longer term?” Robert sees an obvious parallel in monasticism: Buddhism must have a strong institutional presence, with career practitioners, to root itself in America and counteract the prevailing destructive culture.

It’s clear that impending retirement has only inflamed Robert’s passion for ideas even more. Looking back, he’s pleased with his choice of academics as his primary way of teaching Buddhism. “I’m so glad that I became a professor rather than a dharma center person,” Robert says, “because it gave me a day job, and I didn’t have to try to have an empire.”

That is, as long as you don’t consider Tibet House, Menla, years of fruitful activism, and thousands of students educated in Buddhism an empire. Let’s call it a karmic kingdom of Buddhology that’s not going anywhere, retirement or not.