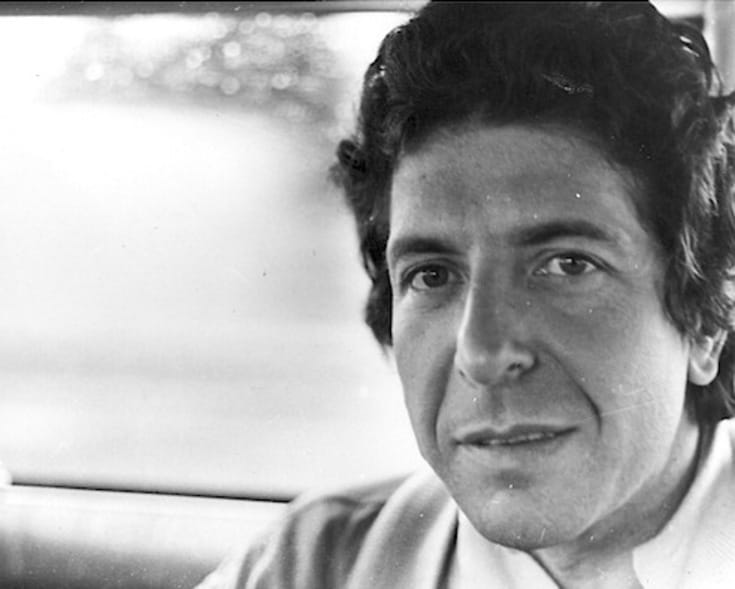

Through the long hot nights of summer and early autumn I have been listening to the ten newest songs from Leonard Cohen, almost unbearably sad in their themes and beautiful in their bareness, yet turned sultry and smoky and rich with a full-bodied looseness thanks to his collaborator in life and in art, Anjani. The songs on Anjani’s album (as it is officially), Blue Alert, are all about goodbye and “closing time” and passing away from the scene. “Tired” is the word that recurs, and “old,” and the picture that Cohen uses for himself on the back cover (as the album’s “producer”) makes him look out of focus and almost posthumous, fading from our view. Yet when such songs of parting and old age are delivered by a young, fresh, commanding woman singer, they take on a much more complicated resonance. Sweet as much as bitter, with the echo of spring in the dark of early winter.

The album has stayed with me, almost every evening, because the paradoxes with which Leonard Cohen has always played so mischievously, so meticulously, take on new flesh and blood here, and show us a man—with a woman beside, and inside, him—who has passed through his stress and is not going anywhere except toward a final nowhere. The ceremonies of farewell have been mounting in recent years on his recordings. On Ten New Songs, in 2001, Cohen featured his co-singer, Sharon Robinson, on the album cover with him, and her husky, aromatic back-up often drowned out his aging growl. On his last album, Dear Heather, in 2004, he offered a drawing he’d made of a sylph or Muse (who looks very much like Anjani) on the cover—no picture of himself—and on at least two songs let Anjani more or less take over. Now he releases a whole collection of new songs in camouflage, as it were, delivered by his companion, and as if to say that it doesn’t really matter who or where they come from. It’s almost as if the songs, looking at death with a voice that never cracks, taking leave of everything with a due sense that much has been enjoyed, issue from someone already absent, or were sent in by his ghost.

Cohen has always held us by writing songs of naked desire and songs of monastic longing, and playing the one off the other: the ladies’ man who is impossible because, deep down, he’s reaching out for surrender. On his first album, his goodbyes were addressed to the women he was leaving to continue his quest. On recent albums his songs had very much the feel of Mount Baldy Zen Center in L.A., where, living as a monk, he really had taken leave of everything. Now, fully back in the sensual world (sharing a small house in L.A. with his daughter Lorca, Anjani just around the corner), he is writing of physical love with the wholeheartedness of someone who doesn’t have other things on his mind. He’s got his monastic stirrings out of his system, one feels, enough to take another being into his life. “Co-production” has rarely had a warmer implication.

The songs are tinglingly sensual, of course, full of an erotic charge and suggestiveness made keener, more piquant, I’m sure, by years in a monastery (where every swaying of a skirt, every echo of some perfume, becomes potent). In the very first song, “Blue Alert,” we have a woman touching herself in the long night, and soon there are lovers lying down under a mosquito net, “to give and get,” a woman with “my braids and my blouse all undone.” The very slowness of the songs allows one to dwell on every drawn-out syllable. But the shock and excitement of the new work comes, in part, from the fact that some parts are written—and delivered—in a female voice. The shiver is hers, not her aging admirer’s. And when she describes her “yellow jacket with padded shoulders” or how her “shoulders are bare,” one gets an immediacy of detail that in Cohen’s traditional work would have given way to wider philosophizing (or at least to his favorite word, “naked”). Other songs, while sung by Anjani with an ache and a sweetness and a robust sense of elegy that are all her own, sound as if they come from a man—Cohen himself—and sometimes the voice seems to go back and forth within the same song between the woman and the man. Goodbye to dualism!

The process of making a final departure from this world has been on Cohen’s mind for quite a while now. But when I listen to the songs on Blue Alert, I feel that I am seeing, sometimes for the first time, what all the monastic training is about. Even such immortal poets as Derek Walcott (in “The Bounty”) offer nostalgia, wistfulness, as they start to close up shop; even the masterful Philip Roth rages against the dying of the light, bewildered, on the run, taken aback, in his later work (The Dying Animal and Everyman). Cohen, by comparison, wastes no time at all on regret or feeling sorry for himself. This phase has ended, his tunes might be saying. But a new one is being born, Anjani’s ringing voice announces.

No need to go deep, he says, true to his later positions, “the surface is fine.” No need for extensive farewells or talk of “what might have been”; he got half the perfect world, and a love that went as far as the innermost door. On the previous album, Dear Heather, he offered a song, “Nightingale,” (sung by Anjani) that was so bright and cheerfully colored, about building a house so he could hear this sweet bird of youth sing, that it sounded as if Leonard Cohen had been retired and reborn at once. Here Anjani gives the song a second try, and turns it into something slow, stately, almost a hymn. A ditty becomes a threnody when the delivery is changed. It’s all in the phrasing.

In the last song of the album, the words “Thanks for the dance” are offered again and again, jauntily, courteously, with a tinkly melody; and they become increasingly sad, truly piercing, only when you realize that they might be coming from someone who’s talking of the dance that is life. The summer of 2006 was a grand one for Leonard Cohen, with a documentary celebrating him (I’m Your Man) coming to theaters, and his first book of poems in at least twenty years, The Book of Longing, arriving in our shops. He was to be found, suddenly, on magazine covers, on radio interviews, in New York, L.A., Montreal. After the shock and drama of being defrauded of nearly all his money by someone he trusted, he showed up again in our midst as if nothing had changed, and he was just the person he’d always been (so careful to say he was not cut out for Buddhism and didn’t get anything much out of his years at a Zen temple—other than the remarkable companionship and stimulation of his ageless Roshi—that you can be pretty sure he did).

Here we are back in the “tower” that first he mentioned in his very first song, “Suzanne”; there’s talk of sins, and being “forgiven,” as there’s always been (though the phrase “mine against yours, yours against mine” gains an almost physical frisson when you think of two bodies lying against one another). Just as on his first album he took the cover photo in a 25-cent public photobooth, here all the photos are taken by daughter Lorca, around the house.

Yet the beauty of late Cohen is that, even more than before, it’s all about the private world, the inner view. Leonard Cohen has had his time in the limelight, playing games with the media, with images of his self, never failing to provoke a response of some sort with his calculated gestures and dry, outrageous pronouncements. But that was always something separate from his work, which moved people—and captivates them to this day—because of a sense of privacy and honest that can’t be faked. He made his nakedness our own.

Now he emerges in public again, and the songs are Anjani’s, and there is a real sense that this is the record of their love and togetherness, her dazzling voice playing with and off and against his grave wisdom (as with such Zen poet-monks as Ryokan and Ikkyu, famous for the young female companions they aquired in their later days). One of the great early poems of Cohen, “The Mist,” from forty-five years ago, appears here, but its three soon-disappearing verses about not leaving a trace on someone are haunting, almost parabolic, when associated with a writer who is seventy-one (from a twenty-five-year-old buck, they would just suggest a loss that he can cancel out with the next conquest). Another song turns San Francisco into almost a mystical vision of life here on Earth. The Golden Gate is still gold and still great, but then the fog comes in again, and it’s gone, and there’s a long drive home, and you lose sight of that lovely old symbol, even though we all remember the sea. Impermanence becomes a form of radiance.

Perhaps the best way of summing this all up is “Never Got to Love You,” in which a man, by the sound of it, says goodbye to a love by noting that he never got to love her as he’d heard it can be done. If you dwell on that sentiment, delivered to someone you care for, it could break your heart with all the things we failed to do or say. James Salter’s beautiful book of short stories, Last Night, published last year when he was eighty, reverts constantly to an old man, nearing his time, going over all the roads in love he failed to take. But here in Anjani’s singing, which has so little sorrow in it, and in Leonard Cohen’s phrasing, which sees the past as dead and gone, it doesn’t just rend the heart, it restores it.

The songs on Blue Alert are moody, melancholy, low-key, as the words “blue” and “blues” suggest. But they’re also “alert” as ever, wise to the games of the mind, attentive to the fact that moods and melancholy and low-key songs are themselves not to be trusted because they’re passing, too. Through almost forty years of recording albums, Leonard Cohen has always given his productions naked, minimalist titles (from Songs to Recent Songs). Here he gives the melodies (and the perfectly minimalist musical arrangements) to Anjani and offers us a title that brings every sorrow and radiance together. Blue, but not black, warning and warming us with the same breath. Death’s on its way, and yet life’s all around.