Of all the people who have ever lived on our planet, one could argue that no one has been more influential than the person known to us as the Buddha. He was a remarkable individual who discovered valuable truths and spent a long life sharing them systematically and publicly. The trail of dominoes he set in motion has wound its way through large, heavily populated areas of the world for a very long time.

The man himself is buried under so many layers of myth that there is not much we can rely on to gain access to what kind of a person he may really have been. Yet there is one character trait that stands out as true because it is common to three episodes found in all renditions of his life story. This is the fact that the Buddha had an unusual ability not only to apply himself fully to anything he undertook, but, more importantly, to turn away from it and find a new way forward when he realized it was not effective—even when he was under duress to conform.

Siddhartha was in search of a deeper wisdom, a solution that penetrated into the very nature of human suffering and showed how to end it once and for all.

This is first demonstrated when he walked away from a privileged upbringing to join a counterculture of forest-dwelling ascetics. The world he was raised in was quite content with pursuing a life of sensual pleasure, as long as one also worked to gain wealth and did one’s duty as a member of the elite ruling class. As a prince named Siddhartha he was groomed for this world, but turned away from it to search for something more meaningful.

While his parents wept and no doubt many others considered him mad for doing so, he renounced his status, gave away all his possessions, and wandered forth to live a life of physical hardship and spiritual struggle. Gratification of the senses and the enjoyments of worldly success seemed to him shallow and pointless if human life inevitably ends in old age, sickness, and death.

He learned the ancient arts of meditation from a series of teachers, and here demonstrated for a second time the same ability to follow his own path in the face of great pressure to do otherwise.

As the wanderer now known as Gautama, he quickly mastered the concentration skills used to attain subtle and exalted mental states, and was invited by his teachers to join them as a leader of their community. While this would have entailed honor and prestige among his fellow wanderers, he turned down the offer and set off again to follow his own path. Meditation was a valuable practice but only a temporary refuge. He was in search of a deeper wisdom, a solution that penetrated into the very nature of human suffering and showed how to end it once and for all.

In the next phase of his life, the man who would become the Buddha took up the practice of extreme asceticism, following the guidance of peers who were convinced that by turning away from all pleasure and embracing pain one could root out the desire that holds a person in bondage to rebirth. Starving himself to within an inch of his life, he eventually realized that this too was not leading to any extraordinary insights, and decided to start eating normally. This incensed his companions, who accused him of being weak and giving up too easily. Yet once again he was able to measure the value of a practice using his own experience rather than by accepting the opinion of others, and once again he set out alone to find another way.

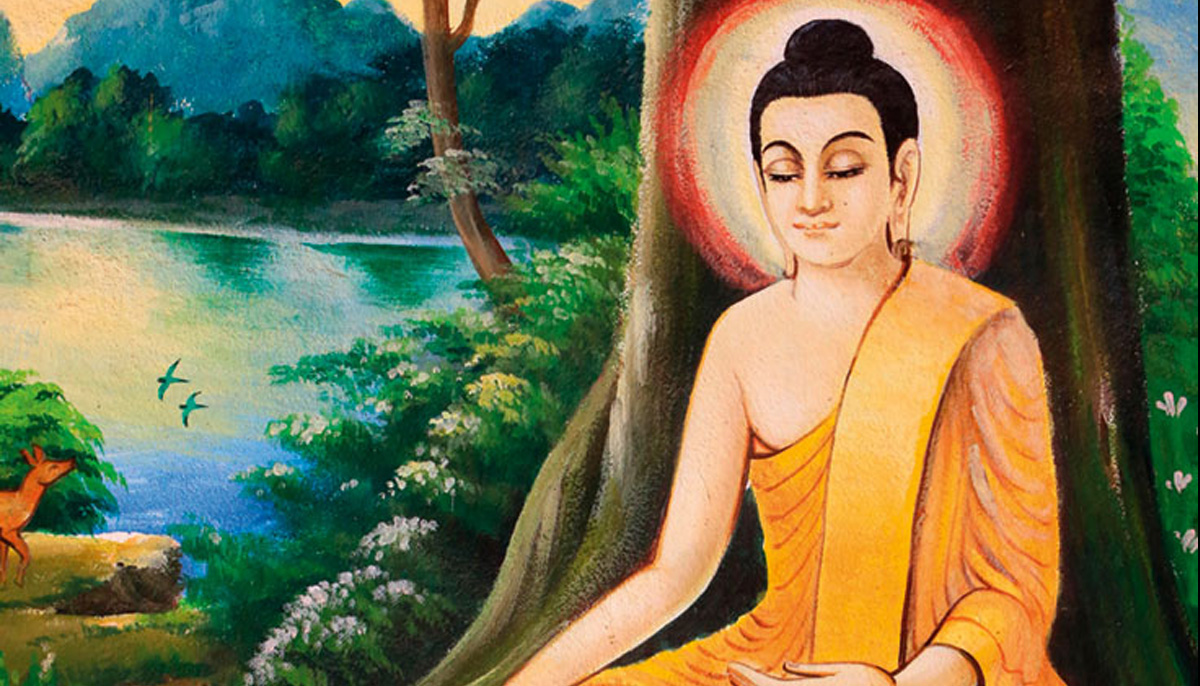

Before long the wanderer Gautama, seated under a tree on a single particular night, had the transformative experience after which he became known as Buddha, “one who is awake.” What was the nature of this experience, and how did it change him so profoundly? What happened to him under that tree? However else it came to be understood over the centuries, we can be sure it involved a deep psychological transformation.

The Buddha’s inner explorations had revealed suffering to be caused by three toxic emotional traits buried deep in the human psyche. When triggered by the pleasure/pain reflex, they emerge again and again as unhealthy mental states that cause unskillful and harmful behavior. Among these are greed—the craving to pursue, acquire, and hold on to anything that feels good—and its opposite, hatred, the craving to resist, destroy, or push away anything that feels bad. Together, greed and hatred serve to keep us discontented, always wanting our experience to be different than it is, either more pleasant or less painful.

The third and most important toxin, he realized, was delusion—a basic ignorance pervading all our perceptions and views, leading us to presume the world is more stable than it is, to assume gratification is more sustainable than it is, and to think of ourselves as more substantial than we actually are.

With meditation the Buddha was able to see the world as the unfolding of a process rather than as a collection of things. He saw that every moment is different, every event is unique, and each transient phenomenon arises and passes away in deep interrelationship with other phenomena. Human experience consists of episodes of consciousness in which information gathered by the senses is felt as pleasant or painful, interpreted to fit a narrative, and responded to in skillful or unskillful ways. When greed, hatred, or delusion are present, blazing like fires that scorch the mind and body, suffering is born; when these are absent, suffering goes to rest.

That night under the tree of awakening, the Buddha extinguished the fires of greed, hatred, and delusion, becoming a person within whom they were “fully quenched” (nirvana). As he described himself soon after his awakening: “All attachments have been severed, the heart’s been led away from pain; tranquil, one rests with utmost ease, the mind has found its way to peace.” This is a description not of cosmological transcendence but of deep psychological healing.

One of the first things the Buddha did after his awakening was form a community, a sangha, originally composed of monks but later to include nuns and laypeople. As time went on, a large and well-organized community of followers formed who lived a “middle way” lifestyle—neither indulging in sensual pleasures nor tormenting themselves with strict austerities. He instructed these followers with discourses on his teachings, which they memorized (as was the custom in this preliterate age), guiding them in ethical behavior, training their minds with meditation, and helping each develop their insight. One by one, many were able to clear their minds entirely of toxins and “wake up” as he had done, at which point they were free of suffering and were known as “worthy ones” (arahants).

For forty-five years, until his death at age eighty, the Buddha would walk the length of the Ganges river basin, teaching as he went. When on tour he would walk about ten miles in the morning, eat a freely offered meal before noon, then retire to a quiet spot for an afternoon of meditation. In the evening, he instructed his community of followers. On full moon and new moon nights, all the monks and nuns of a given area would gather to meditate, recite the texts, and attend to community affairs. When the monsoon rains made the rivers impassable, they would all settle into huts for three months of retreat.

Not long after his awakening the Buddha won the support of powerful kings and wealthy merchants, which contributed greatly to the success of his life’s work. He rejected caste distinctions in his community and created a safe and dignified place for women; both were radical innovations for his time. He is credited by later Hindu tradition for abolishing the then common practice of animal sacrifice, and his teachings inspired great and compassionate rulers both in India and far beyond.

The deeper legacy of the Buddha’s life was his illumination of the inner landscape of experience and of the empowerment that accompanies self-knowledge. This is what struck a chord as the tradition wound its way through southeast and central Asia, and then across Tibet, China, Korea, and Japan. It is why his teachings continue to have such a profound effect on the modern world and the emerging global civilization.

The Buddha showed that whatever is out there in the world and whatever happens to us externally, what really matters, in terms of our own health and well-being, is our internal response to it. When we react unskillfully, triggered by primitive reflexes of craving and ignorance, we harm ourselves and others. But we are also capable of acting with equanimity and wisdom, thereby accessing the more evolved qualities of generosity, kindness, and understanding.

The historical Buddha embodied the next phase of evolution, pointing the way for all of us to become more noble human beings.