How does one write a “biography” of a classical text? Such an undertaking suggests that the text, over time and across cultures, grows and changes, that it has its own life. In The Lotus Sutra: A Biography, Donald Lopez promises to trace the various roles of the Lotus Sutra as it has traversed the globe — and he delivers.

Lopez opens the book with a succinct overview of the content of the Lotus Sutra, skillfully setting the stage for the following chapters on the Lotus Sutra in India, China, Japan, “across the Atlantic” (though actually from India and Nepal to Europe and then to Boston), and finally on the Lotus Sutra in the twentieth century and its journey “across the Pacific” from Japan to the Americas. Through this biographical approach, Lopez elucidates many of the critical questions about the Lotus Sutra for which there are answers: How did the text identified as the Lotus Sutra develop? How was it understood and used in various times and cultures? But it is a more fundamental and challenging question that drives much of the book: What is the Lotus Sutra?

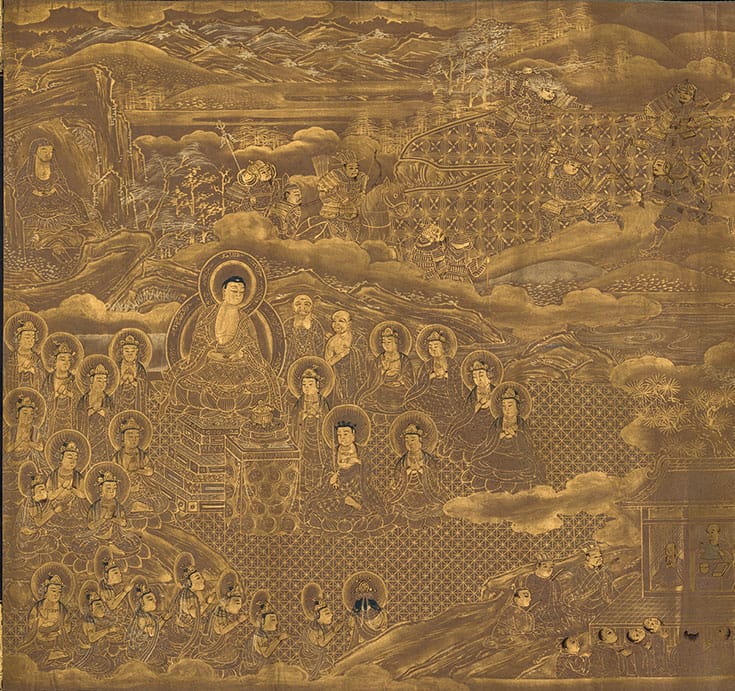

The Lotus Sutra has had immeasurable influence in East Asia, especially in the Mahayana traditions of China and Japan. It was the focal point for the Chinese Tiantai (Jpn., Tendai) Buddhist tradition and is considered the only scripture necessary for our times by the Japanese Nichiren traditions. It has also had broad cultural influence in literature and the arts.

A fundamental and challenging question drives much of the book: What is the Lotus Sutra?

The sutra itself is a mixture of sometimes seemingly unrelated chapters, making it difficult to pinpoint its overall purpose and theme. One major theme, however, is that all people should seek — and are indeed promised and even destined—to become buddhas. A supporting theme concerns the various skillful means that the historical (and transhistorical) Buddha used (and continues to use) to help people attain this goal. It encourages various bodhisattva-like altruistic practices and provides concrete examples of them. The sutra is also insistent (though not uniquely so) in praising itself not only as the ultimate teaching of the Buddha but also as a worthy and efficacious object of devotion.

by Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

Lives of Great Books Series,

Princeton University Press, 2016

257 pages; $29.95

Our modern understanding of the Lotus Sutra is complicated by an ambiguous textual history. There are many surviving Sanskrit versions — some only fragments — but the origins of the text remain obscure; there appears to be a core text, to which various miscellaneous chapters were added over the years. There are also numerous Chinese translations, again of varying content, but the most important is the superb translation by the fifth-century scholar – monk Kumarajiva. It is his translation on which scholars and followers of East Asian Buddhism tend to focus and rely, often unconsciously assuming that it alone represents the Buddhism of the Lotus Sutra.

This brings us back to the question that Lopez wrestles with throughout this book: What is the Lotus Sutra? It’s easy to say that the Lotus Sutra is the Chinese translation by Kumarajiva, the text that is most read by devotees and the one that has had such a profound influence on East Asian Buddhism. But there are many differences between the Kumarajiva translation and extant Sanskrit manuscripts of the Lotus Sutra and other classical Chinese translations of the text, to name a few. And the Lotus Sutra itself speaks of another “Lotus Sutra,” one that was revealed over and over again many aeons ago and embodies the ultimate truth of the buddhadharma. Even into the final pages of the book, Lopez wrestles, as he does many times throughout the volume, with this vexing, most thorny, question. Perhaps the best answer is that the Lotus Sutra is saddharma—the transhistorical “true dharma,” the “real” or final teaching (whatever that is) of the Buddha (whatever that is), of which Kumarajiva’s text is only one—though the most salient—explication. But does this really answer the question? In short, this book is a biography of a book, one that admits in its final pages that one cannot ultimately answer the question of what that book really is. It is a challenge that Lopez leaves with the reader.