From just sitting to cooking as practice, Dogen defined how most of us understand Zen today. Steven Heine on the life and global impact of Dogen Zenji.

The Japanese Buddhist teacher Dogen (1200–1253) is perhaps best known as the founder of the Soto school of Zen, which promotes the practice of single-minded, unremitting seated meditation (zazen), also referred to as “just sitting” (shikantaza). Soto Zen remains one of the largest denominations in Japan today, with nearly fourteen thousand temples throughout the country and two head temples: Eiheiji, founded by Dogen in the deep mountains north of Kyoto, and Sojiji, based on the lineage of fourth patriarch Keizan, which relocated from northwest Japan to Yokohama in the early twentieth century.

Dogen is also celebrated as one of the greatest representatives of East Asian Buddhist philosophy, and Buddhist thought more broadly. Since the end of World War II, when his teachings began to be widely disseminated in the West, with some of his main works now translated in several versions into English and various European languages, Dogen’s reputation has been expanding internationally. His exacting approach to sustained meditation, along with a strict adherence to the minimalism and diligent discipline of traditional monastic life, sometimes referred to as the attitude of making “just the right amount” (oryoki) of effort, has greatly influenced a multitude of zazen meditators and other contemplatives and spiritual seekers in America and elsewhere.

On a theoretical level, his masterwork, the Treasury of the True Dharma Eye (Shobogenzo), is considered one of the greatest examples of worldwide religious writings. A collection of diverse lectures on doctrines and rituals given by Dogen over the course of twenty years, and further edited by Soto monk-scholars over the centuries, its key passages have been compared to classical philosophy and medieval mysticism, as well as modern psychology, physics, and environmentalism. As a philosopher, Dogen has been ranked with Aristotle and Augustine, Hegel and Heidegger, and as a poet with Walt Whitman and Gary Snyder, as well as, in the Japanese context, Kukai, Saigyo, and Basho.

What is the basis of the tremendous impact exerted by Dogen, both on Zen and international spiritual perspectives? As Dogen himself was aware, his life and outlook unfolded at a crucial crossroads in the social and cultural history of East Asia in two main ways.

First, just at the time he was born, Japanese society was undergoing a radical transition from four centuries of peaceful rule by the Fujiwara aristocracy to the dominance of the warrior class in the Kamakura era. The newly empowered samurai class fully embraced Zen training methods because of their emphasis on self-control and self-reliance, although its leaders were often torn whether to use these skills to support or reject actions on the battlefield. In 1248, Dogen was in fact offered, but declined, the chance to become the private teacher and leader of a temple built by the shogun, Hojo Tokiyori, who a few years after this interaction stepped down to join the Rinzai Zen sect.

Second, Dogen was one of the first great Japanese teachers in the thirteenth century who traveled to China. In the 1220s, he spent four years there and transmitted to Japan the teachings and rituals of Zen. At that time, Zen was beginning to fade in importance on the Chinese mainland, but was taking hold in Japan and was poised to expand rapidly with the support of the shogun.

Dogen played a crucial role in the development of Zen in this period, introducing many kinds of practice, such as meditation conducted in the Monks’ hall; a new layout for temple design featuring the Dharma hall that replaced the Buddha hall; the delivery in the monastic compound of various kinds of formal and informal sermons; an emphasis on the value of the chief cook and other seemingly lower level temple officers; and the use of poetry to express fundamental philosophical truths, especially during ceremonies and celebrations.

At the same time, Dogen sought to strip ritual activities from the traces of esoteric rites that were upheld at a couple of prominent early Zen temples in Kyoto, including Kenninji, founded by Eisai in 1202, and Tofukuji, established by Enni Ben’en in 1243. Both followed streams of the Rinzai sect based on Chinese teachings that, in medieval Japan, often became rivals with Dogen’s lineage.

To appreciate the achievements attained during his monastic career, Dogen’s lifetime can be divided into four main stages lasting about a dozen years each. During each stage, he faced and resolved a particular challenge to self-understanding and its function in developing an innovative view of the Zen institution.

1. The Formative Period

The first, or formative, period (1200–1213) revolves around Dogen’s admission to the monkhood and decision, after experiencing a “great doubt” (daigi) about mainstream practice methods, to thoroughly explore the path of zazen.

This stage begins with Dogen’s aristocratic background in Japanese court society, including his high level of Buddhist and secular education as a child growing up in the capital. Dogen had connections to the fading but still powerful Fujiwara regency clan on his mother’s side, and to the emerging Minamoto samurai clan derived from his father, who was also a descendent of the imperial family.

At age seven, Dogen was orphaned after his mother’s death. He experienced profound feelings of evanescence and was determined to renounce society. Five years later, after rejecting an opportunity to become a court official, he was ordained as a Tendai priest on Mount Hiei, located to the northeast of the capital.

There, Dogen quickly became deeply disillusioned because of a sense of grave misgiving about the doctrine of original enlightenment (hongaku). If all beings in the universe already possess the endowment for awakening, he asked, what is the need to carry out austere meditative practice? This doubt propelled him to take leave of the dominant Tendai sect to join the fledgling Zen movement initiated in Japan by Eisai.

2. The Transformative Period

The next stage, from 1213 to 1227, encompasses the new religious path Dogen started after he quit Mount Hiei and began training at Eisai’s Kenninji temple in central Kyoto before eventually attaining an experience of enlightenment in China.

At Kenninji, zazen meditation was featured as the primary, though not exclusive, practice technique for the first time in Japanese Buddhist history. It is said that Dogen briefly met Eisai, who led other Zen temples in Kamakura and Kyushu, before he died in 1215. Dogen stayed at Kenninji from 1217 to 1223, although not much is known about these years of his life.

A decade after leaving the Tendai sect, Dogen undertook a four-year journey to China in the company of Eisai’s foremost disciple, Myozen, who died prematurely in 1225, with his remains later returned to Kenninji by Dogen. That same year, Dogen met his Chinese mentor Rujing in an intense face-to-face encounter (menju) and began studying closely with him. Dogen gained a breakthrough to liberation by “casting off body-mind” (shinjin datsuraku) and thereby earned the transmission of the Soto lineage.

3. The Reformative Period

The third, or reformative, period (1227–1243) begins with Dogen’s slow-starting efforts to establish Soto Zen in Japan and culminates with the formation of a thriving monastic compound.

After six transitional years from the time of his returning “empty-handed” (kushu) to his home country, during which he struggled to gain a substantial following, Dogen became very successful in opening the first authentic Chinese-style monastery in Kyoto. The practice center, named Koshoji, featured the first Dharma and Monks’ halls in Japan.

Here on the outskirts of the capital, Dogen started to produce many outstanding writings, including the Treasury of the True Dharma Eye and the Extensive Record. He earned the patronage of the powerful one-eyed samurai Hatano Yoshishige, who supported the rest of his career. However, because of Fujiwara family objections to Dogen’s novel approach to Buddhist teaching, as well as other complex circumstances that are still not entirely clear, Dogen decided to move his assembly during the summer of 1243 to a provincial site long celebrated for its splendid landscapes.

4. The Performative Period

Finally, the period from 1243 to 1253 covers the fulfillment of Dogen’s mission to become leader of a genuinely reclusive Zen monastery before his death. This he did at Eiheiji, where he remained true to the methods of meditation and ritual he almost single-handedly imported from China to Japan. Once ensconced at the new cloister, Dogen left the mountains only once for the rest of his life, for a six-month visit to the Hojo shogun in the garrison town of Kamakura.

At Eiheiji, Dogen put greater emphasis on the functions of clerical discipline, especially the performance of daily chores based on the dignified daily demeanor that he saw as linked to a deep understanding of the universal impact of karmic causality. This trend seems to represent a divergence from some of the views he endorsed while leading Koshoji, where the technique of just sitting meditation prevailed and there was a greater sense of inclusiveness of women and lay practitioners. In 1253, he went to Kyoto for medical care and died in zazen posture.

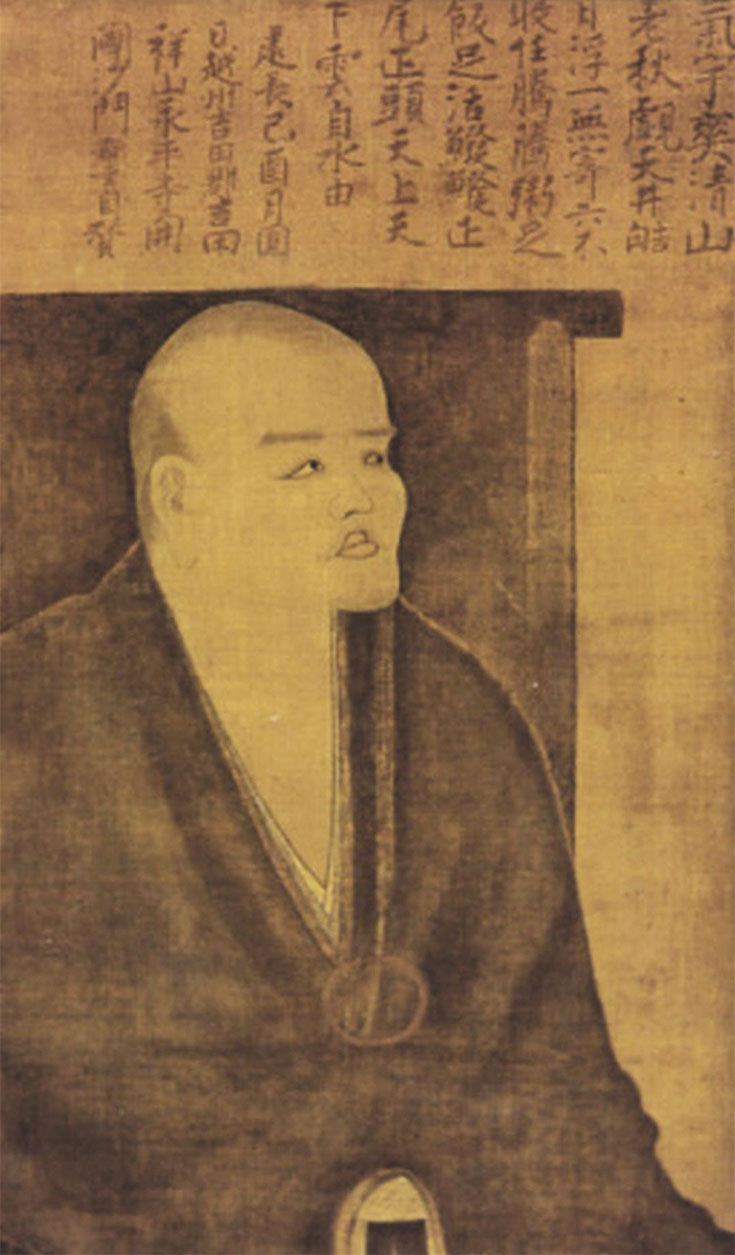

Although Dogen had a sense of his long-lasting originality and creativity, one of his poems, originally an inscribed verse for his portrait that was composed near the end of his life, expresses a humble and self-deprecating standpoint characteristic of the first Zen patriarch, Bodhidharma, who gazed at a cave wall for nine years:

If you consider this portrait to be real, then who am I, really?

But why put it there if not to give people a chance to know me?

When you look at this painting,

And think that what hangs in empty space embodies the real me,

Your mind is clearly not one with wall-gazing meditation.