As Rochester Zen Center celebrates its 50th anniversary, Zen teacher James Ishmael Ford reflects on that community’s unique importance, and that of its founder, Roshi Philip Kapleau. Meeting him, Ford recalls, was an emotional moment.

While widely acknowledged as a genuine Zen master, and the source of a significant and widely accepted stream of Western Zen, Philip Kapleau — founder of Rochester Zen Center and author of several books including the monumentally important The Three Pillars of Zen — in fact lacked formal dharma transmission from his teacher. Here the contradiction of a generally accepted Zen teacher who has not received the “formal seal” of his teacher has most clearly focused and challenged Western Zen’s understanding of legitimate authority.

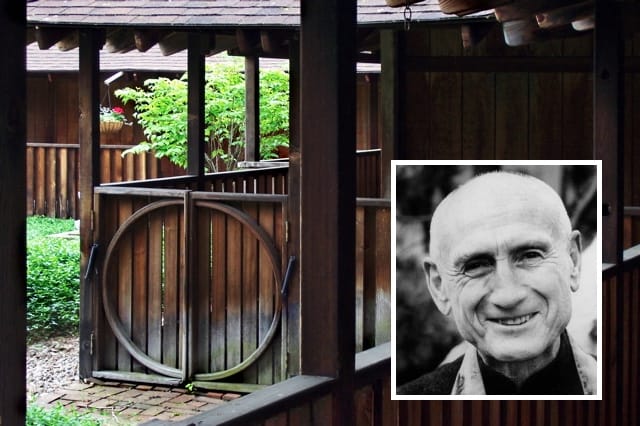

In August 2003 the American Zen Teachers Association conference was hosted by Kapleau’s Rochester Zen Center in Chapin Mill, their country retreat, outside of Rochester. Those of us who were interested were invited to go into Rochester and meet Philip Kapleau Roshi. He was ninety years old and suffering from advanced Parkinson’s disease. Most of us understood this could be our last, and for some only, chance to meet this old Zen pioneer.

I actually hesitated. He had broken from his teacher Yasutani Roshi many years before. He took to calling himself Roshi and was known in subsequent years to make seemingly self-serving disparaging remarks about other teachers. He also, it seemed to me, gratuitously challenged the technical veracity of the transmission of the lineage from which he had broken — which was a lineage in which I also practiced. But he was also the editor of Three Pillars of Zen. I cannot fully express how important that single book was in my life; and this has been true for so many others who’ve taken up the Zen way. So, in the end I went to see him.

Philip Kapleau was living in a small two-room apartment at the center. His Parkinson’s was so advanced he could do little more than sit in his recliner and hold hands with each of us who’d made the trip. About ten teachers—dharma successors in the Soto, Rinzai, Harada-Yasutani, and Korean Chogye traditions — had made the pilgrimage. There was little option, if we wanted to shake Kapleau’s hand, but to kneel in front of him and take the initiative. It had clearly not been set up to require such a supplicative posture, but that was inevitably what was called for.

I found tears welling up from deep within me — not just for his physical condition, but for gratitude. This crusty old man was a true founder and absolutely one of the most important figures in bringing the Zen way West. For all his flaws, he was a great man and one of the most important people in my life. I happily knelt, took his hands in mine, and thanked him. I remain grateful for that opportunity.

Philip Kapleau was born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1912. He served as chief court reporter for the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, and later he was also court reporter at the trials in Tokyo. While in Japan he met a number of prominent Zen teachers, including Soen Nakagawa, Sogaku Harada, and Haku’un Yasutani, the founders of the Harada-Yasutani line of koan-studying Soto Zen. After coming back to America he felt profoundly dissatisfied with his life and decided to return to Japan in 1953.

After spending three years at Hosshinji with Harada Roshi, Kapleau became the first Westerner to begin formal study with Haku’un Yasutani. After some twenty sesshins with Yasutani, the roshi confirmed Kapleau’s awakening. In 1966, after ten years studying with his teacher, he came home to America and, with Yasutani Roshi’s permission, founded the Rochester Zen Center in upstate New York.

There are several accounts of the reasons for his famous break with Yasutani Roshi. The most commonly reported version suggests deep disagreement about appropriate forms for the nascent North American center. Another story is that Kapleau objected to the close association of his teacher to another senior student who Kapleau felt was lax in his ethics.

Philip Kapleau was an aggressive personality who rubbed a number of people the wrong way, including several visiting Japanese teachers. More important, there were the growing tensions between Yasutani Roshi and Philip Kapleau. The specifics are debated but these tensions appear in significant part to have to do with Kapleau’s leadership of his center: his increasingly independent style, his departures in liturgical usage, and his relationships with visiting teachers.

The tensions all came to a head when Yasutani Roshi informed Kapleau that he, Kapleau, would no longer be considered Yasutani’s student. At this time Kapleau had completed about half of the Harada-Yasutani koan curriculum, the koans in The Gateless Gate and The Blue Cliff Record. Could he, in good faith, continue to teach considering his permissions were limited to introducing people to the practices of the Sanbo Kyodan—or “Three Treasures,” as the Harada-Yasutani school called itself—to which he no longer belonged? Regardless Kapleau decided to continue as a teacher.

The Three Pillars of Zen was the first book in English to describe authentic Zen training, and it justly became an international bestseller. Kapleau went on to write a number of other books, and his center grew to become one of the most influential Western Zen communities. While seen by many as a difficult personality inclined to unnecessary conflict, he was also a central figure in the establishment of a Western Zen. There should be little doubt the institution he founded will continue well into the future.

But the Rochester lineage, as it is sometimes called, opens all the questions regarding the nature of dharma transmission. What does this mean for us today and in the future? Andrew Rawlinson, who spent years studying Western teachers of Eastern religions, makes a pointed comparison of Philip Kapleau and Robert Aitken, as an aid to reflection on the nature of formal transmission—what it might mean, and what it probably doesn’t mean. Philip Kapleau spent thirteen years in Japan studying with several teachers. Eventually he received permission to teach but not dharma transmission, which is the approval to teach independently. Since his split with Yasutani Roshi, Rawlinson wrote before Kapleau’s death:

Kapleau has continued to teach, as he is entitled to do, but has also given dharma transmission to a number of his own students, which, according to the transmission criteria of the Zen tradition, he is not entitled to do. Or at least, these appointments need not be recognized by any other lineage or teacher.… In effect, then, Kapleau has created his own Zen lineage.

By contrast, Rawlinson holds up Robert Aitken (who would die in 2010):

Aitken received dharma transmission from [Ko’un] Yamada Roshi but he has been far more radical in his attitude to the traditional way of life than Kapleau. He has encouraged Zen (and Buddhist) feminism, for want of a better term, and has actively encouraged gay and lesbian participation in Zen (though he is not gay himself). He is also a committed social activist—he was a co-founder of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship — and sees such commitment as a necessary aspect of Buddhist ethics, which are themselves expressed in the precepts. At the same time he has given Dharma transmission to one of his students who is a Christian priest.

This last action is something for which Aitken has been openly criticized.

As Rawlinson sees it, the difference between these two teachers turns on their understanding of transmission: “In short, for Aitken transmission is a necessary condition (though not a sufficient one) for the tradition to continue; for Kapleau, spiritual qualities hold an equivalent place.”

Roshi Kapleau died on the sixth of May, 2004, in the garden of the Rochester Zen Center, surrounded by old and new students. He had suffered from the ravages of Parkinson’s disease for years and had long since retired from formal teaching. It is hard to assess yet what Roshi Kapleau’s career means for the development of Western Zen. But one thing is certain: despite having teaching authorizations, he ultimately lacked formal dharma transmission, yet he created a lineage that is largely recognized throughout the Western Zen community. (Among the most prominent of Kapleau Roshi’s heirs are the late Toni Packer, current RZC abbot Peter Bodhin Kjolhede, and Sunyana Graef, who guides the Vermont Zen Center near Burlington and Casa Zen in Costa Rica.) Thus his life and the institution he created forces Western Zen practitioners to carefully consider the nature of dharma transmission.

As an heir within a traditional lineage and as someone deeply involved in the transmission of Zen into our Western culture, Kapleau Roshi’s presence and legacy offered me a challenge and a pointer. The challenge was that to my mind he was completely and authentically a Zen teacher, but lacking the tactile authorization. The pointer was to go beyond the over blown rhetoric of the Zen way’s transmission, and to accept that it is in fact the transmission of a way, a style and and approach.

And specifically what we’re invited into is a more humble and I believe more authentic Zen. The transmission as something passed on from teacher to student is useful. And I’d be wary of anyone who lacks it. But, it also has something to do with the community. And I have learned to be wary of teachers who lack that. So, for me there need to be two other things to create an authentic Zen community of practice. One would be students who accept the teacher. And also other teachers who accept the teacher. You have that and you have Zen.

What we see in Kapleau Roshi’s gift of dharma successors are authentic Zen practitioners and teachers, pretty much any of whom I’d be completely comfortable entrusting the spiritual care of any of my students. For these gifts, I honor the memory of our founding Western master, Roshi Philip Kapleau.

This article was adapted from Zen Master WHO? A Guide to the People and Stories of Zen, by James Ishmael Ford, with permission of Wisdom Publications. It has been updated and expanded by the author for publication on LionsRoar.com.