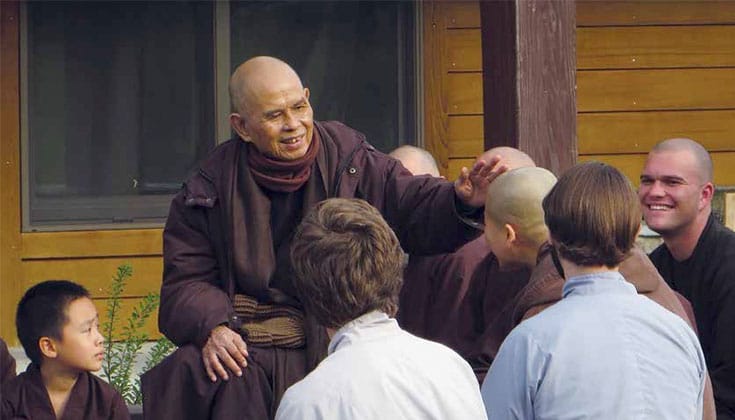

Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh has a soft, feathery voice. It is, we are informed, twenty decibels lower than average, so even when he’s using a microphone, we must be perfectly quiet in order to hear him.

“It was fifty years ago on this very day,” he nearly whispers, “that Martin Luther King gave a famous speech with the title ‘I Have a Dream.’” Thich Nhat Hanh, or Thay, as he is affectionately known, pauses.

“From time to time,” he says with a smile, “I have a nice dream also.”

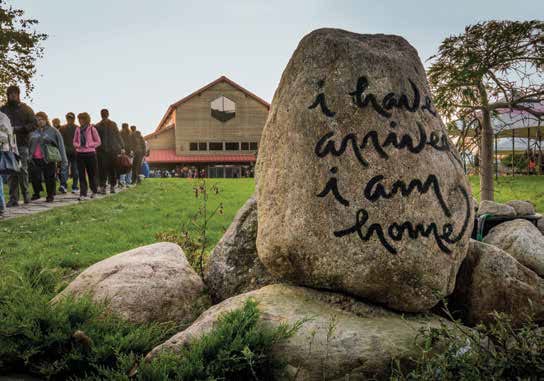

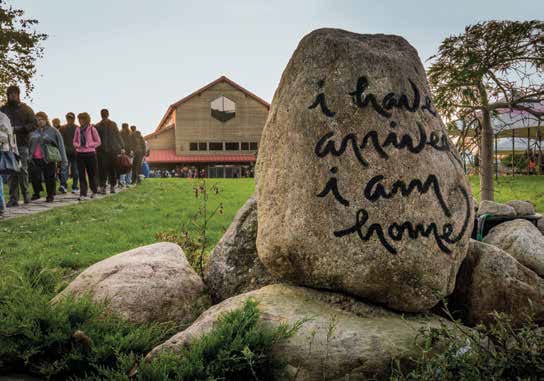

This is the beginning of today’s dharma talk, and the beginning is always my favorite. It’s addressed especially to the children. From the toddler who likes to yodel during silent meals to the woman sitting in front of me with the pure-gray ponytail, there are more than eight hundred people on this six-day retreat. We are at Blue Cliff Monastery in Pine Bush, New York, and the theme we’re exploring is “Transformation at the Base: The Art of Suffering.” In other words, it’s the very essence of the Buddhist path. Suffering is the inevitable common denominator of life. Buddhist practice transforms it into happiness and liberation.

“I’ll tell you one of my dreams,” Thay continues. “I had it about twenty years ago, when I was very young.” The eighty-six-year-old monk smiles at the quiet joke he’s cracking. “I was something like sixty-six. Very young.”

Yet in his dream, he was even younger, maybe twenty-one or twenty-two, and he was overjoyed because he’d been accepted into the class of his university’s best professor, a man who everyone said was exceptionally wise and kind. But on his way to the classroom for the first time, Thay saw a young man who looked exactly like him. He knew this young man was no other than himself and he wondered if the other him had also been accepted into the prestigious class. He stopped in to the administration office to ask.

“No, no, not him,” declared the lady in the office. “You, yes, but not him.”

Thay left the office confused and grew more so when he learned that the illustrious professor was a professor of music. Not being a music student, Thay couldn’t understand why he’d been accepted into this advanced class. Then he opened the classroom door, and inside there were over a thousand students, and the view through the window looked like Tusita Heaven—all waterfalls and mountain peaks covered with snow.

Surprise after surprise, Thay was informed that he had to give a music presentation as soon as the professor arrived. What was he going to do? Looking around for a solution, he put his hand in his pocket and felt the bowl of a small bell. Because he was a monk, the bell was the one instrument he was a master of, so with a happy heart, he waited for the professor’s arrival. “He’s coming, he’s coming,” Thay was told, but he never did get a glimpse of the professor. In that moment, Thay woke up.

“I stayed very still in my bed,” he tells the Blue Cliff retreatants, “and I tried to figure out what the dream meant.” Thay realized that the young man who looked exactly like him was a self that he had left behind.

“Because I’d made efforts to practice,” he says, “I overtook myself. That is why I was accepted, and he was not. In the process of practice, you become your better self with more freedom, more happiness.”

The music class, according to Thay, symbolized an assembly of advanced Buddhist practitioners, while the professor symbolized the Buddha himself. “I regret that I did not have a few more minutes in the dream,” Thay quips. “If I had, then I would have seen the Buddha in person.”

During the Vietnam War, Thich Nhat Hanh was sleeping when a grenade was hurled through his window. He would have died, but it hit a curtain and ricocheted, exploding into the next room. On another occasion, grenades were thrown into the dormitories of the School of Youth for Social Service, an innovative grassroots organization he founded to improve education, sanitation, and farming practices in poor, rural communities. These grenades left two volunteers dead, a young man paralyzed, and a young woman riddled with a thousand pieces of shrapnel.

Thay and those working with him did not take sides in the war. No matter what the political allegiance of a victim, they would help him or her, and for this they were persecuted by the Vietnamese government and communists alike.

On June 1, 1965, Thich Nhat Hanh wrote a letter to Martin Luther King, Jr. in which he compared the struggle for peace in Vietnam to the civil rights movement in America and explained why some Vietnamese monastics felt driven to self-immolate. Now, half a century later, Thay offers that same explanation in the quiet of the Catskills.

“Both warring parties wanted to fight to the end, and we were caught in the middle,” he says. “We wanted an end to the hostilities, but we did not have magazines, radio, or television, so our voice was lost in the bombs. That is why, in order to get the message across, we sometimes had to burn ourselves alive. Self-immolation was not an act of violence. It was an act of sacrifice in order to awaken the world to the suffering of the people in Vietnam.”

One year after writing this letter, Thay was traveling across the United States to spread his urgent message of peace and, while in Chicago, he met Martin Luther King, Jr. for the first time. Subsequently, King came out publicly against the war and nominated Thich Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize, claiming that he knew no one more worthy than “this gentle monk.”

Later they saw each other again in Geneva, where they were both attending a peace conference. “I was able to tell him that the people in Vietnam admired him and called him a bodhisattva, a great being,” says Thay. “He was pleased to hear that. We also discussed sangha building. The expression for sangha that he used was ‘beloved community.’

“That was our last meeting before he got killed. When he was assassinated, I was in New York. I was angry and got sick. But I told myself I had to continue. I vowed that I would continue the work of sangha building.”

Community is crucial, according to Thich Nhat Hanh, because without it no one can accomplish much. Even the Buddha needed a sangha, and the first thing he did when he got up from under the Bodhi tree was to establish one. Thich Nhat Hanh, however, found himself abruptly cut off from his sangha. After speaking out for peace, he was exiled from Vietnam and it would be almost forty years before he could return. “I was like a bee without a beehive,” he says, “like a cell taken out of the body. I knew that if I did not practice well, then I would dry up.”

He took political asylum in France and began gathering some friends around him. In the beginning, the sangha was so small that they had nowhere of their own to practice and had to ask the Quakers for the use of their space. Now Thich Nhat Hanh’s sangha includes hundreds of monastics and tens of thousands of lay practitioners, with communities everywhere from Argentina to Austria, Botswana to Brazil.

I look around at the sangha in the Great Togetherness Meditation Hall at Blue Cliff. A week ago, I knew almost none of these retreatants, but now I know these painful facts: There’s a man here whose son was killed in Sandy Hook Elementary School and another whose marriage is crumbling. There’s a woman whose father is ill and another whose daughter died of leukemia.

There is suffering. That is the first noble truth. There is personal suffering; there is societal suffering; and there is the tragic place where personal and societal suffering meet. But in community all of our suffering—in being heard and held—can soften, just a little.

“You are part of my sangha,” Thay says to all of us.

The retreatants at Blue Cliff are divided into dharma families, small groups named after birds, trees, flowers. As families, we come together for mindful work and dharma discussion. When Willow, my family, gathers to talk, we always begin by giving each other our internal weather reports. Today, after we delve into our sunny skies, soft fogs, and snowstorms, Peggy Smith, one of our dharma discussion leaders, holds out a singing bowl. “Does anyone want to invite the bell?” she asks.

Peggy likes that in this tradition the bell is invited, never struck. She likes this careful, nonviolent attention to language. Step-by-step, we go through the ceremony for inviting the bell.

First, bring your palms together and bow. Next, place the bell in the center of your palm, thinking of your hand as a lotus flower and your fingers as its five petals. If you close your fingers around the bell, its sound will be stifled, so keep them open, fully bloomed. In and out, take two breaths. Then with the bell inviter—the little stick—gently tap the edge of the bell. This half ring is called “waking the bell” and it lets those around you know that soon there will be a full ring. This is an opportunity for everyone to stop what they’re doing and simply enjoy the moment. Follow your breath for another eight seconds, or ten if you’re generous. Then invite the bell fully. The sound, as Thay describes it, should be like a bird soaring up. Take three deep breaths and invite the bell again. And again—three breaths and one final invitation.

Lynd Morris is the Willow family’s other discussion leader. She explains that when Thay talks about a bell of mindfulness, he’s referring to more than just a metal instrument. “A bell of mindfulness can be anything that reminds you to come back to yourself,” she says. It can be a sound, such as a kettle whistling or a baby crying, but it doesn’t have to be. On this retreat, Lynd has been using doorways. Every time she passes through one, she pauses, breathes in and out, and allows the doorway to remind her to say hello to herself and the world around her.

At home, Lynd rings a bell before meals. When she introduced this practice to her children, she described the intent as listening until you could no longer hear the last little bit of vibration. “There was instant focus,” she remembers. “It was a kind of game. It was playful.”

Thich Nhat Hanh recommends that every family have a bell. It’s also helpful, he says, if there’s a mini-meditation hall in the house. It can be a whole room or just a corner—all you need is space for a few cushions and maybe a flower. Every morning and evening the family can gather in the mini-meditation hall and invite the bell. They can also invite it whenever the atmosphere in the house is not peaceful.

“Whether you are a child or an adult, you have the right to invite the bell,” says Thay. “When you want to cry, when you’re irritated, you can go to that small room in your house, invite the bell, and breathe. Maybe Mommy is in the kitchen cutting carrots. When she hears the sound of the bell, she knows that her child is practicing, so she stops cutting carrots and enjoys breathing in and out. And maybe Father is at his desk. He also hears the sound and stops to practice. That is the most beautiful landscape you can see. I think every home in the twenty-first century should have a bell and a mini-meditation hall. That is civilization.”

My dharma family’s bell is sitting on a red and green cushion shot through with gold thread. When it’s my turn to invite, the instrument feels cool in my hand. Breathing in, breathing out, the whole family recites together:

Body, speech, and mind in perfect oneness, I send my heart along with the sound of this bell. May the hearer awaken from forgetfulness and transcend the path of anxiety and sorrow.

The first time I try to bring the inviter to the bell’s lip, I bring it down too gingerly and miss. I try again and the bell wakes. Each time I invite the bell, my dharma family says with me:

I listen, I listen. This wonderful sound brings me back to my true home. I listen, I listen. This wonderful sound brings me back to my true home.

In his speech “Let Freedom Ring,” commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington, President Obama has requested that today at three o’clock people across the country ring bells to proclaim that America still has a dream to realize.

“The dream of Martin Luther King included civil rights and jobs,” says Thich Nhat Hanh. “But we know we need more than that. We need peace in ourselves, our family, our nation.

“Today, according to the wish of President Obama, we will ring a bell, but our way of ringing the bell is a little bit different. With the bell, we take good care of ourselves and restore peace inside. We know how to handle a painful emotion, because the bell helps us go back to our true home. Coming back to ourselves, to our beloved ones, and to our dear planet Earth—that is the real dream.”

Mindfulness practice helps us cultivate peace in ourselves, and from that foundation we can engender peace in others. Yet if we do not have a sangha, our practice can easily grow weak. This is what Thay emphasizes, as did Martin Luther King: community is key.

It’s after lunch and clouds are gathering. Thick and gray, they make me think of what Thay said during one of his recent dharma talks: the nature of a cloud is no birth and no death.

“When you look into tea, what do you see?” he asked. “I see a cloud. Yesterday the tea was a cloud up in the sky. But today it has become the tea in my glass. When you look up at the blue sky and you don’t see your cloud anymore, you might say, ‘Oh, my cloud has died.’ But in fact, it has not. When I look mindfully into my tea, I see the cloud, and when I drink my tea, I drink the cloud.

“You are made of cloud—at least 70 percent of you,” Thich Nhat Hanh continued. “If you take the cloud out of you, there’s no you left. A cloud has a good time travelling. When it falls down, it does not die. It becomes snow or rain. The rain becomes a creek, and the creek flows down and becomes a river. The river goes to the sea, then heat generated by the sun helps the water evaporate and become a cloud again. Now the cloud has become tea, and Thay is going to drink it. Then what will become of this tea? It will become a dharma talk.”

It might be my imagination, but I think a cloud just manifested into a drop of rain falling on my shoulder. I don’t say anything, though, and Peggy Smith and I stay where we are under the imperfect umbrella of a large tree. She has pink cheeks and bobbed hair and is wearing the brown jacket of an Order of Interbeing member, which means she has taken the fourteen mindfulness trainings, or precepts, with Thich Nhat Hanh. She’s telling me how she handles a strong, difficult emotion.

“I go through a process of recognizing the reaction in my body,” she says. “I assure myself that it’s a stormy cloud in the sky and it will pass.”

Suddenly, as if on cue, a non-metaphoric cloud breaks open, leaving Peggy and me rushing to take shelter under the dining tent. We settle into chairs and I pose another question: “Thay is always talking about the importance of sangha. How does the sangha support you?”

Her answer, in short, is that it keeps her from being afraid. “For instance,” she says, “the day the United States started to bomb Baghdad, there was a group of us who wanted to talk to our senator and express to her our deep disappointment. But her office—the whole building—was locked, so twenty people decided to lay down in the intersection in Portland, Maine. As we approached the intersection, I thought, ‘It’s March—it’s going to be so cold. How am I going to ever do this?’ But I lay down and closed my eyes, and Thay was right there. And then the sangha was right behind him. It was one of the best meditations I’ve ever had in my life. I was so disappointed when the police interrupted it to arrest me!”

I thank Peggy for the interview. With the rain now pelting down on the white tarp above, it’s getting difficult to hear her and a crowd is gathering. It is three o’clock, time to let freedom ring.

A stone’s throw away, Thay and clutch of people with umbrellas are under a tree inviting the big bell—breathing in, breathing out. We form a messy, accommodating circle under the dining tent that expands into two layers to let everyone in. Line by line, a man reads one of Thay’s poems and the rest of us repeat it. We are a powerful human microphone that can be heard even over the thunder:

I walk on thorns, but firmly, as among flowers.

I keep my head high.

Rhymes bloom among the sounds of bombs and mortars.

The tears I shed yesterday have become rain.

I feel calm hearing its sound on the thatched roof.

Childhood, my birthland, is calling me,

and the rains melt my despair.

Rain, tears, tea. The clouds above look interminable, but Thay teaches that they can and do transform. He says, “If you don’t practice, you do not know how to handle your suffering and you continue to cry a lot.” Yet with mindfulness, tears become rain. New growth follows.

Holding hands, we sing “Amazing Grace.” We sing “We Shall Overcome.” We sing “Wade in the Water.” And for a moment, I have to put my hand over my chest. Like Peggy said, I can feel a strong emotion manifesting in my body. An achy pain, it’s half grief over the seemingly endless sorrow of this world. But it’s also half joy because here under this tent there is so much love that I think maybe—just maybe—we really will overcome.