In the United States, there is a rich and varied range of Theravada teachers, practices, and communities. There are hundreds of Theravadin temples, monasteries, centers, and communities.

To better understand the landscape of American Buddhism, I interviewed more than two dozen senior Theravada teachers in the US. I wanted to draw a more comprehensive map of American Theravada, but I likely omit many important teachers and communities. I hope others will pick up where I leave off.

Theravada is considered an orthodox Buddhist tradition. It emphasizes adherence to the teachings of the Pali Canon — the earliest recorded teachings attributed to the Buddha — and its commentaries. Theravada is most common in Sri Lanka and mainland Southeast Asia.

In North America, Theravada is often seen as focusing on meditation. In truth, meditation is one aspect of the tradition, which also includes important components, such as:

- the cultivation of generosity alongside moral precepts and ethical training;

- an understanding of karma and its laws;

- study of the Pali Canon and its commentaries and sub-commentaries;

- a range of community services, including outreach and social welfare programs;

- support for immigrant and refugee communities;

- and much more.

To many traditional Theravadins, this larger framework is important. Bhikkhu Bodhi, a leading American Pali scholar and translator, is wary of practicing meditation “without sufficient appreciation of the context in which these techniques are set and [without] the principles and auxiliary practices that should accompany and support meditation practice.”

In America, “Theravada” is also often equated with Insight Meditation and the “vipassana movement.” This is, in part, a racially-informed oversimplification, as both of these communities are predominantly white. Media coverage of American Buddhism often marginalizes or outright ignores Asian-American Buddhists.

While practicing in alignment with the Buddha’s original teachings of liberation is a common goal in Theravada, between various teachers and practitioners there are nuanced and often heated debates about how this is best achieved. My intention was to survey this range without holding any single perspective as “authoritative.” To ensure the range of teachings were adequately represented, I relied on interviews and direct quotes whenever possible.

The Vipassana View

Vipassana, or Insight Meditation, is the meditative form most often associated with Theravada. It is also the inspiration behind many secular mindfulness teachings, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction.

Vipassana is often thought of as a tightly-defined meditation technique. In truth, it is not a homogeneous teaching or technique but can refer to a wide array of practices, generally geared toward understanding the Buddha’s teachings of the Four Noble Truths, the three marks of existence, dependent origination, and the eightfold path, with the goal of liberating the heart and mind. Some teachers emphasize particular systems or methods of practice, while others do not.

The sociological implications of what Mahasi Sayadaw did were enormous — returning the possibility of liberation to lay people.

—Sharon Salzberg

Three particularly popular vipassana lineages emerged in Burma during the 20th century. Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw and U S.N. Goenka are well-known in the United States for their systematic approaches to intensive meditation practice. The third teacher, the late Venerable Mogok Sayadaw, is hugely popular in Burma but his teachings are not as well-represented in the US.1

The Satipatthana Sutta is held by many as the most comprehensive overview of traditional Theravadin meditation practices, yet these same practices are subject to an array of practical and technical interpretations. For instance, a well-known framework of Theravada meditation distinguishes between two basic types of practice, insight meditation (vipassana) and calming or tranquility meditation (samatha). But in a more traditional and canonical understanding, vipassana is not a type of meditation at all. “Vipassana actually refers to the direct seeing of the real nature of phenomena,” says Bhikkhu Bodhi, “thus what a person would practice are meditation techniques that lead to vipassana.”

Mahasi Sayadaw’s Revolution

Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw (1904-1982) was a great Burmese monk. At a time when most Burmese meditation techniques were taught to monastics only, Mahasi Sayadaw and his students also instructed thousands upon thousands of lay practitioners. Sharon Salzberg, a well-known convert Buddhist American lay teacher authorized to teach by Mahasi Sayadaw, explains, “The sociological implications of what Mahasi Sayadaw did were enormous — returning the possibility of liberation to lay people.”

Many of Mahasi Sayadaw’s senior monastics have taught in the United States, including the late Sayadaw U Pandita. Some of these monks immigrated to the United States, often overseeing multiple Burmese-American and multiethnic communities. Mahasi Sayadaw’s teachings have also become popular in some traditionally Mahayana communities; for instance one of the country’s most senior monastics, Bhante Khippapanno – also known as Hòa thượng Kim Triệu – often teaches the Mahasi Method to his Vietnamese-American students.2

Mahasi Sayadaw’s method of teaching is known today as the “Mahasi Method.” It includes mindfulness of breathing focused on the abdomen, mental noting, and a very slow style of walking meditation. This system is outlined most clearly by Mahasi Sayadaw in his book The Progress of Insight. Well-known within this system is Mahasi Sayadaw’s formal map of awakening, which corresponds to commentarial Visuddhimagga explanations of the path.

Ashin Pyinnya Thiha teaches the Mahasi Method at the Mahasi Satipatthana Meditation Center in New Jersey. “I teach mindfulness meditation based on Mahasi Sayadaw’s way according to the Mahasatipatthana Sutta,” Bhante Pyinnya explains. “If the student follows the Mahasi Method or way of practicing,” says Bhante Pyinnya, “[they] can get the progress of sixteen kinds of insight knowledge through the seven stages of purification.”

The center where Ashin Pyinnya Thiha teaches is a part of the America Burma Buddhist Association (ABBA), the U.S. affiliate of the Mahasi Meditation Center of Burma. Like most monastic traditions in the U.S. and Asia, the ABBA community is sustained through donations, while all ABBA activities including residencies and retreats are offered free of charge. This model of teaching is fundamental to the traditional Theravadin framework: the Dharma is considered priceless; therefore, there can be no cost associated with it. Thus monastics freely support the community in a variety of ways, including teaching. In turn, monastics are deeply dependent on the generosity of lay community support – Theravadin monastics cannot handle money, cook, or even store food.

In this way, monastics and lay practitioners alike cultivate the parami of dana, which is translated as generosity, giving, or charity. Dana is not simply a financial or economic practice but rather a way of cultivating the heart, and cultivating communities, through an ethos of mutual interdependence and responsibility. While many American lay centers have modified this understanding of dana in a variety of ways, there are a few notable exceptions including the communities maintained by Santikaro, Gil Fronsdal and Andrea Fella, and the centers in the tradition of U S.N. Goenka, all of which operate solely based on dana.

U S.N. Goenka, Global Teacher

U S.N. Goenka (1924-2013) and his teacher Sayagyi U Ba Khin (1899-1971) were Burmese laymen who emphasized ten-day intensive meditation courses (retreats), primarily for lay practitioners. There are numerous centers around the world offering courses in the tradition of U S.N. Goenka (respectfully known as Goenkaji) and Sayagyi U Ba Khin, including twelve centers in the States.

“Sayagyi U Ba Khin and Goenkaji wanted the Dhamma to reach as many people globally as possible… and Goenkaji prided himself on teaching exactly what his teacher taught,” says Barry Lapping, the head teacher at the Dhamma Dhara Vipassana Meditation Center in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts.

“The teaching is presented via audio and video recordings of Goenkaji in order to maintain the consistency of the technique worldwide,” explains Lapping, while “the conducting teachers run the course, give guidance to the students, meditate with the students and answer their questions.” While the centers do not track specific demographics of their students, “there are courses for different communities based on language, including Khmer, Burmese, Hindi, Mandarin, Cantonese, and Thai.”

In keeping with the traditional Theravadin emphasis on dana, all centers are supported solely by donations. “An important principle in this tradition is that no one should have to pay for the teaching, and no one should profit by it,” explains Lapping. Course teachers and volunteers do not receive any financial compensation; students understand that everything they receive is from those who previously sat courses and they, in turn, have the opportunity to donate so others can receive the same benefits in future retreats.

At the beginning of each course, students take the five moral precepts and then develop a base of concentration (samadhi) through anapanasati or mindfulness of breathing. On the fourth day, students begin vipassana practice. “They learn to move their attention systematically through the body,” says Lapping. Cultivating equanimity in response to all sensations is key to the method.

“To experience the body, you must be aware of what is happening in the body — that is, vedana — sensations,” says Lapping. “Similarly, whatever happens in the mind — any thought, emotion, recollection — is reflected by sensations in the body. Vedana is the key that allows us to observe the entire mental-physical structure and develop equanimity.”

If you watch the breath — or anything else you might be noticing — then you can also know that there is the mind that’s watching the breath. And when you’re watching the breath, you can also know everything attendant to the breath, like your feelings and your thoughts.

–Moushumi Gosh

While U S.N. Goenka was his best-known student, the late German-American Ruth Denison was also a disciple of Sayagyi U Ba Khin, although she eventually modified her teachings in ways that diverged from her teacher. Her women’s retreats were particularly popular among LGBTQ women. “She offered a gateway, an open door to the Dharma, to lesbians who might not otherwise have chosen to enter into Buddhist practice,” explains biographer Sandy Boucher. Boucher adds that Arinna Weisman, a student of Denison, was one of the first teachers to offer LGBTQ-specific retreats, co-taught by Eric Kolvig.3

U S.N. Goenka was a major influence on many Insight Meditation Society teachers. “The Buddha did not teach Buddhism, he taught a way of life,” Salzberg recalls U S.N. Goenka saying, a perspective which is now key for many in mainstream as well as secular Buddhism.

The Streams of IMS and Spirit Rock

In 1975, the founding of Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts catalyzed an extraordinarily popular and influential current within mainstream American Buddhism. Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield, Sharon Salzberg, and Jacqueline Mandell (née Schwartz), all of them Jewish converts to Buddhism, were the center’s founders and early core teachers. Today, IMS — along with the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies,4 the Forest Refuge, and its de facto sister center Spirit Rock in California — serves as a hub for dozens of formally and informally connected teachers, centers, and practitioners. Spirit Rock, in particular, has grown to become a major player in the Buddhist world in its own right since its founding in 1987. As Lion’s Roar reported in a 25th-anniversary profile of Spirit Rock, the center was by that time serving 40,000 visitors a year.

Blending Theravada lineages is a hallmark of IMS and Spirit Rock. Important early teacher-lineages included Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw; Anagarika Munindra and Dipa Ma, students of Mahasi Sayadaw; Sayadaw U Pandita, a successor of Mahasi Sayadaw; Venerable Ajahn Chah; and U S.N. Goenka. “Munindra was extremely open-minded in his approach,” says Goldstein. “I think that’s where I derived that basic framework of openness for my own practice and understanding.”

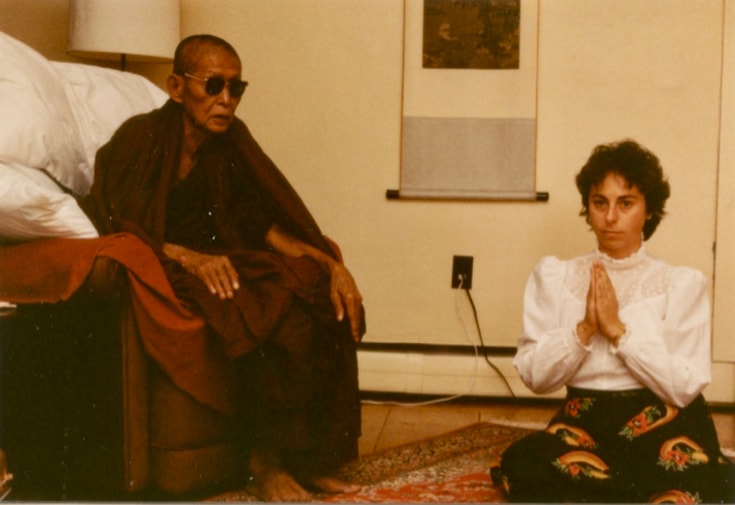

For Salzberg, the master laywoman Dipa Ma was “hugely important… She was the person who told me to teach.” A close student of U S.N. Goenka, Jacqueline Mandell was encouraged to teach in the States by Venerable Taungpulu Sayadaw and Dr. Rina Sircar. “Taungpulu Sayadaw taught by temperament,” says Mandell. “He individualized the practices.” The late Taungpulu Sayadaw and Dr. Sircar were also important teachers in Burmese-American communities. It was Sayadaw U Pandita who taught Sharon Salzberg the metta practices that would later become a fixture at IMS and Spirit Rock retreats.

Unlike Mahasi Sayadaw and U S.N. Goenka, Venerable Ajahn Chah did not offer students a systematized or standardized map of practice. In his book Bringing Home the Dharma, Jack Kornfield summarizes Ajahn Chah’s teachings as “using every experience as your practice… opening up to each experience to see what is happening… learning to let go… [and recognizing] the one who knows how to rest in wisdom and equanimity.”

Both centers maintain connections with monastic communities, and many IMS and Spirit Rock teachers also train in outside traditions, including Advaitin, Dzogchen, and Western psychotherapy. In February 2019, IMS changed their mission statement to reflect that the center is aligning themselves with “Early Buddhism” rather than Theravada — a change that could herald Theravada reforms in the 21st century.

In recent years a handful of IMS and Spirit Rock teachers, organizing themselves under the auspices of the Wisdom Streams Foundation, have practiced and taught under Burmese monk Sayadaw U Tejaniya.5

Moushumi Ghosh, Sayadaw U Tejaniya’s English translator, explains one of Sayadaw’s central teachings: “If you watch the breath — or anything else you might be noticing — then you can also know that there is the mind that’s watching the breath. And when you’re watching the breath, you can also know everything attendant to the breath, like your feelings and your thoughts.”

Expanding the Refuge

In 1983 Jacqueline Mandell formally left the Theravadin tradition. Prompted by the historical as well as contemporary gender inequality in Theravada Buddhism, Mandell wrote about her decision in the first issue of Inquiring Mind.

“It needed to be said from a place of leadership,” Mandell reflects now. “I realized I had an ability to say something and maybe it would make a difference.”

Mandell’s push toward equality heralded an important turning point in the development and expression of the Dharma at IMS and, later, Spirit Rock. To this day, both institutions strive to address inequality, diversity, and inclusion.6 The organizations are now focusing on addressing racism and increasing leadership opportunities for people of color and LGBTQIA people.

“Our lessons learned will increase the rapidity at which we can integrate and bring about transformation in other areas,” explains DaRa Williams, one of the African-American teachers at the helm of these initiatives.

Many white teachers at IMS and Spirit Rock, says Williams, are also working to understand how intersectionality informs their own life experiences. “It’s been hugely rewarding, for me personally,” says Joseph Goldstein, “and also for the institution, to see all the work being done — it’s been tremendous.”

In recent years, the growing number of POC and LGBTQIA practice communities associated with IMS and Spirit Rock have attracted more and more young people to the practice. The Against the Stream (ATS) communities — often overseen by hip, tattooed and streetwise teachers — were also popular among younger practitioners until allegations of misconduct by founder Noah Levine surfaced in 2018 and the community disbanded. Some of the teachers from ATS have started a new socially-minded Buddhist group under the name “Meditation Coalition,” which also promises to attract a younger demographic. All in all, there is an increasing focus on making teachings more accessible to young people.

Yet the cost of IMS and Spirit Rock retreats remain prohibitive for many, although both centers offer some significant scholarships, and formerly incarcerated persons can sit IMS retreats at no cost.

The centers’ underlying economic models are a modified form of the traditional Theravadin ethic — the retreat fees contribute to the centers’ annual operating costs, while most teachers and some staff do not have fixed incomes but are dependent on additional donations (dana) offered by students and retreat attendees. Subsequent to the widespread influence of IMS and Spirit Rock, this model has been adopted by many of the country’s lay residential and nonresidential centers.

Changing Landscapes in Asian-American Communities

Sri Lankan-American monk Venerable Bhante Seelawimala, of the American Buddhist Seminary, says he is concerned about decreased engagement in younger Asian-American Theravada Buddhists. The ABS website writes that many monastics “lack sufficient background in developing communication skills with these immigrant children who are growing up in America… mainly due to the language and cultural gaps between the monks and the younger generation.”

Conversely, researcher Chenxing Han is studying the nuanced experiences of young Asian-American Buddhists. While not specifically focused on Theravadin communities, Han highlights how many Asian-American Buddhists do not fit into easy typologies of experience or cultural background. In her Buddhadharma article “We’re Not Who You Think We Are,” Han writes, “The young adult Asian Americans I spoke to are both evidence and upholders of American Buddhism’s multivocality.”

Many monastics who immigrate to the U.S. also hope to teach outside of their specific ethnic communities but are unable to do so, explains Ayya Tathaaloka, a white American bhikkhuni (a fully-ordained female monastic) who spent many years practicing in predominately Asian-American communities. “Especially amongst the younger monks, many of them come wishing to share the Buddha’s teachings more broadly,” says Tathaaloka, “but in so many places the connections are not in place.”

Stalwarts of American Jhana

Jhana practice is an important set of traditional teachings not generally found in mainstream mindfulness communities. Jhanas can roughly be understood as very deep and particular types of samadhi, or concentration — though there are many nuances and important debates about the nature of that concentration. In the United States, only a handful of teachers specifically teach jhana practice.

Students sitting the annual IMS and Spirit Rock rains retreats, or practicing at the Forest Refuge, may receive jhana instructions from individual teachers. While these instructions vary based on the teacher’s own training, Joseph Goldstein says, “a number of us learned a particular method from U Pandita Sayadaw, which we have also taught on an individual basis to many meditators [and fellow teachers] over the years.” In this method, metta practice is often used to develop jhana.

Burmese monastic Venerable Pa-Auk Sayadaw’s teachings on jhana are largely systematized, corresponding to the classic treatise Visuddhimagga and sutta maps of practice. In the States, Pa-Auk Sayadaw has many Burmese-American as well as Malaysian-American students, says Tina Rasmussen, one of Pa-Auk Sayadaw’s senior students. Pa-Auk Sayadaw has spent considerable amounts of time teaching in these communities and at the Forest Refuge in Barre, Massachusetts. “Sayadaw Pa-Auk’s teacher told him that part of his dharma, his life’s truth,” says Rasmussen, “was to plant the seeds of the samatha practice in the West.”

In years past, Tina Rasmussen and her husband Stephen Snyder served assistant teachers during some of Pa-Auk Sayadaw’s residencies here, and they continue to teach independently in the States. Since the depth of absorption required by Pa-Auk Sayadaw is quite difficult for many, Rasmussen says, “Sayadaw and his students encouraged us to write Practicing the Jhanas to outline the method of first obtaining jhana.”7

Leigh Brasington was a student of the late Venerable Ayya Khema, a German-born pioneer of the modern Bhikkuni Sangha.”Anybody who studied with Ayya Khema was struck by her clarity,” says Brasington. Ayya Khema learned jhana practices through the study of the Pali canon and commentaries and was later encouraged to teach jhana by the Sri Lankan monk Most Venerable Matara Sri Nanarama Maha Thera.

While following a clear map of jhanic progression, also outlined in his book Right Concentration, Brasington allows students a range of methods for developing concentration. Likewise, when moving from jhana to insight practice, Brasington encourages students to use whichever insight method they prefer. “I figure it’s not so important how you examine reality,” he says, “but that you examine reality.”8

Venerable Bhante Henepola Gunaratana, founder and abbot of the Bhavana Society in West Virginia, also teaches jhana practices. Bhante G, as he is known, was born at a time when meditation practices were largely suppressed in Sri Lanka due to colonialism. Thus Venerable Gunaratana learned meditation through experience, using his knowledge and understanding of the texts as a guide. Known also for his teachings on mindfulness and loving-kindness, his books The Jhanas in Theravada Buddhist Meditation and Beyond Mindfulness in Plain English outline his teachings on jhana.

Venerable Gunaratana also has longstanding ties with the Washington Buddhist Vihara, the country’s oldest Theravada monastic community. While the organizations are not formally linked, the Washington Buddhist Vihara and the Bhavana Society form an important nexus of American Theravada. Venerable Gunaratana has also supported female monastic ordination in the US.9

Bhante Vimalaramsi, a monastic who has reached many students via successful online outreach, also teaches jhana but as a kind of understanding rather than level of absorption.

Forest Monks of Thailand

Throughout the history of Theravada, there have been many monastics who wander the wilderness committed to solitary practice. Renowned master Venerable Ajahn Mun (1870–1949), a Theravada reformer, emphasized such a return to the roots of Buddhism through asceticism, intensive meditation, and rigorous ethical conduct. He established the Thai Forest Tradition based on those principles. Venerable Ajahn Maha Boowa (1913-2011) and Venerable Ajahn Chah (1918-1992) were two of Ajahn Mun’s best-known students.

In the US, many Thai Forest monastics are either white converts or Thai-American, but there is a wide range of community demographics. Wat San Fran serves a predominately Thai-American community and is particularly popular among millennials. On the other hand, Venerable Ajahn Maha Prasert’s temple in Fremont, California has of the most diverse congregations in the country, with Thai-Americans compromising the minority-majority.

Even the name “Thai Forest” itself is something of an ethnic misnomer. “The northeast of Thailand, where Ajahn Chah, Ajahn Mun, and Ajahn Maha Boowa were from,” says Ajahn Pasanno, “it’s an area that speaks a Laotian dialect.”

In the Thai Forest Tradition, there is less of a divide between insight and concentration practice. “Meditative concentration and wisdom may be likened to two wheels of a cart: only when both wheels work in unison can the cart move forward,” says Ajaan Dick Silaratano, a senior student of Ajahn Maha Boowa. Since various students have different capacities for absorption, Ajaan Dick says, “most of the Thai Forest masters refrain from speaking publicly about jhana, preferring to talk about samadhi in more general terms.”

In general, Thai Forest monks have great respect for the natural world. The late Venerable Luang Por Thoon would instruct students, says his student Phra Anandapanyo, to correct wrong perception through observing the natural world. “In your daily life, in the forest, in the city, there’s metaphor in the world,” Phra Anandapanyo explains. “Use that to reflect and look into yourself, make a parallel, and see: okay, perhaps what you believe is wrong and you have to let go of it.”

Convert Buddhists need to pay respects to the history we’re drawing on, not just appropriate the bits we like and then pretend we’re more advanced than Asian-American Buddhists.

—Santikaro

Abhayagiri monastery in Northern California has played an important role in connecting many lay practitioners to the deeper monastic roots of Theravada. Ajahn Chah was hugely popular amongst Thai and international students alike, and it was important to him that his “Western” students establish monasteries in their home countries, to maintain “the traditional [Buddhist] model, of how monastic community and the lay community functions together, creating an integral part of a society or culture,” says Ajahn Pasanno.

Many Thai Forest teachers encourage self-reliance and solitary practice, and they are less likely to instruct students through formalized systems of practice. “The person has to find the technique themselves,” says Ajahn Vuttichai, also known as Phrawoody, a senior student of Venerable Ajahn Jamnian.

Thai Forest teachings often emphasize awareness and the knowing nature of mind. “It’s the ground of one’s practice, what one roots the practice in,” says Ajahn Pasanno, “but it’s also what takes one to a place of, say, liberating the heart.” Ajaan Dick Silaratano, like many Thai Forest teachers, refers to this as “citta, or the mind’s essential knowing nature.”

Thai Forest teachings on awareness have drawn comparisons to the Dzogchen tradition of Tibetan Buddhism.10 In one method, systematized by the late Thai monk Luangpor Teean (1911-1988), the student first learns to cultivate awareness through a traditional rhythmic hand movement. Next, one “learns to ‘see’ thought, as opposed to just knowing that one is thinking,” says lay teacher Michael Bresnan. “After one is able to see thought, then we can be aware of awareness itself.”11

Along with the many American Thai Forest communities,12 Thai Forest teachings have also impacted many convert Buddhist teachers outside of the Thai Forest lineage. Santikaro, a white American lay teacher, says that his Thai Forest training was essential to his understanding of the path, but worries about cultural appropriation. He notes that convert Buddhists need to “pay respects to the history we’re drawing on, not just appropriate the bits we like and then pretend we’re more advanced than Asian-American Buddhists.”

In recent years, a Theravada reform movement with connections to the Thai Forest Tradition, called Buddhawajana