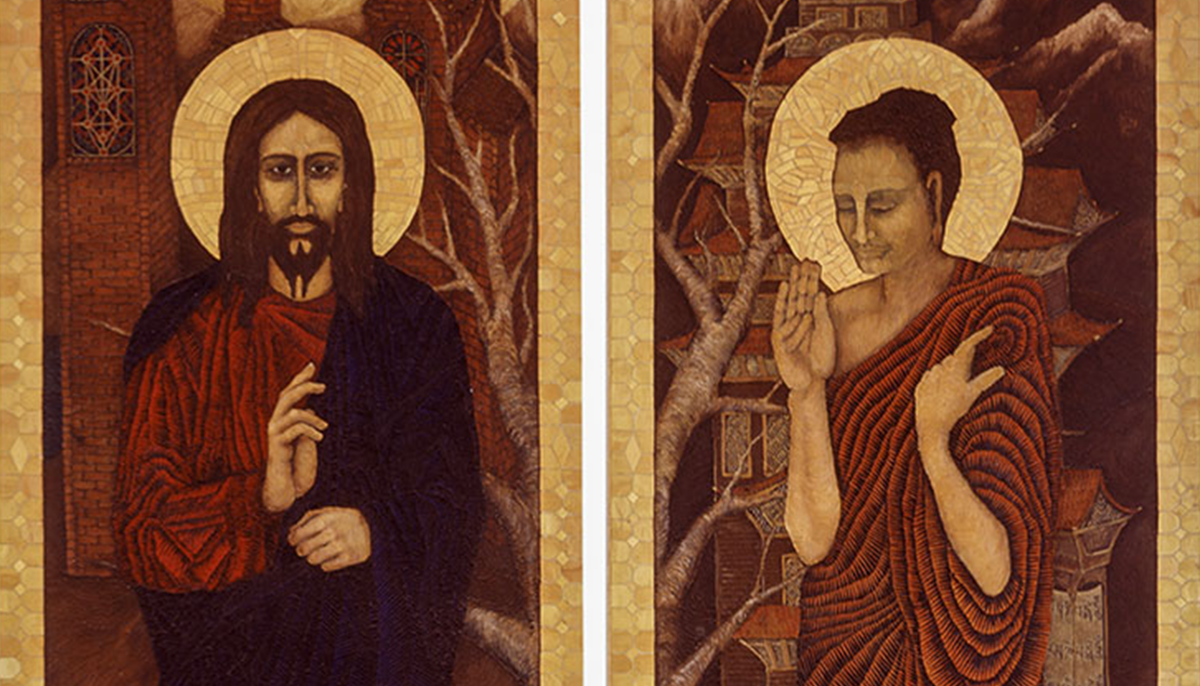

In Buddhism, enlightenment, which is a combination of prajna (wisdom) and compassion, is often called “having the Buddha mind.” In Christianity, St. Paul talks about how Christians are to “have the mind of Christ.” How alike, then, are “Buddha mind” and the “mind of Christ”?

The historical Buddha and the historical Jesus each walked the earth in their day, but it is the living Buddha mind and the Cosmic, or resurrected, Christ that are present among us today. Thich Nhat Hanh talks about the “ontological Buddha, the Buddha at the center of the universe,” which echoes the Cosmic Christ “in the heart of every atom,” as Teilhard de Chardin puts it. I see the Cosmic Christ archetype as a parallel concept to that of buddhanature, or Buddha mind.

It is easy for Christians to forget that the oldest understanding of Christ is as the Cosmic Christ, which predates the Nicene Creed by three centuries. Paul called the Cosmic Christ “the pattern that connects,” which “holds all things together in the heavens and on the earth,” and is the “light in all beings.”

Given this context, the Christ nature is in all of us. “We are all other Christs,” as Dominican friar Meister Eckhart (1260–1229) and twentieth-century Roman Catholic monk Thomas Merton both put it. Merton, incidentally, was a good friend of the Dalai Lama, and when His Holiness was asked one day what kind of God he believed in, he replied, “I believe in the God of Thomas Merton.”

Merton asked in his journal, “Who am I?” and answers, “A Son of God… . My true self is the self that is spoken by God—‘Thou are my Son!’… . Tremendous happiness and clarity (in darkness) is my response: ‘Abba, Father!’”

Zen philosopher D. T. Suzuki, in his classic work Mysticism: East and West, cites Meister Eckhart, who said: “In giving us His love God has given us the Holy Spirit so that we can love Him with the love wherewith He loves himself.” Suzuki says this describes the very meaning of prajna, wisdom, which he said can be described as “one mirror reflecting another with no shadow between them.”

Divinity pours its whole nature into us to the extent that we are empty enough to receive it. For this very reason, emptying is an important part of the path both in Buddhist and Christian mysticism. Christ himself underwent emptying—kenosis—in entering human history.

The Buddha mind is not something esoteric. It is “your everyday mind”—but a mind or consciousness that goes deeper than cultural structures. People often compare it to a mirror, as D. T. Suzuki did. Zenkei Shibayma describes it this way: “The mirror is thoroughly egoless and mindless. If a flower comes, it reflects a flower; if a bird comes, it reflects a bird. It shows a beautiful object as beautiful, an ugly object as ugly. Everything is revealed as it is… . Such non-attachment, the state of no-mind or the truly free working of a mirror, is compared here to the pure and lucid wisdom of Buddha.”

Meister Eckhart responds to the question “How should one love God?” this way: “You should love God mindlessly, that is, so that your soul is without mind and free from all mental activities” and touches “oneness and simplicity.”

He goes on, “Therefore your soul should be bare of all mind and should stay there without mind. For if you love God as he is God or mind or person or picture, all that must be dropped. How then shall you love God? You should love God as he is, a not-God, not-mind, not-person, not-image—even more, as he is a pure, clear One, separate from all twoness. And we should sink eternally from something to nothing into this One. May God help us to do this. Amen.”

Notice the invitation to mindless love—being free from mental activities, baring the mind, “staying there without mind,” and the not-mind and not-person of the Godhead “sinking eternally,” and the irony involved in asking God to help us do this. Elsewhere, Eckhart talks about the need to “pray God to rid me of God”—another ironic statement.

All this is the Christ mind. It is also Buddha mind.

Another dimension to the Christ mind and Buddha mind is that of living and working “without a why,” as Eckhart puts it. He urges us to “return to our unborn self” by emptying and being emptied, and tasting “deep poverty.” What follows is a “breakthrough” in which we learn that “God and I are one.”

Is this different from attaining our “original face” in Buddhism, wherein we discover “not that one sees Buddha but that one is Buddha,” as Merton put it? Eckhart assures us that we know the “changeless existence and nameless nothingness” of Divinity when we undergo “the most powerful” and “noblest” prayer, which is “that which proceeds from a bare mind.” Emptying is important because “the tablet is never so suitable for me to write on as when there is nothing on it.”

Thich Nhat Hanh talks about the “living Buddha inside of us,” while Eckhart talks about “Christ within us,” and the “seed of God within us” that “grows into God.” Says Thich Nhat Hanh: “Dharmakaya is the embodiment of dharma, always shining, always enlightening trees, grass, birds, human beings, and so on, always emitting light. It is this Buddha who is preaching now and not just 2,500 years ago…. He is a living Buddha, always available.” A name for this in Christianity is the “resurrected Christ.”

The Cosmic Christ is the light in all things that emanates from all things. The story of the Transfiguration in Luke’s Gospel tells how radiance emitted from Jesus at the top of a mountain with three friends present. Today’s science instructs us that light is both wave and particle and that photons or light waves are found in every atom in the universe. I see Jesus as a light particle, and the Christ as a light wave. Is that how we can recognize the historical and the living Buddha as well?

Thich Nhat Hanh tells us, “You have the buddhanature within you…. If Shakyamuni, the historic Buddha, has buddhahood, you yourself have your own buddhahood.”

“You take refuge in that nature within you,” Thich Nhat Hanh says, as St. Paul takes refuge in the Christ nature within himself when he says: “I no longer live, but Christ lives in me.”

Eckhart insists that Christ took flesh not just in the historical Jesus or individuals but in humanity as a whole. He goes even further when he says we must give birth to the Son of God just as Mary did.

We birth the Christ whenever we birth compassion, love, or justice. “Compassion is my religion,” says the Dalai Lama. Whether we’re followers of Buddha or Jesus, are we busy birthing compassion?