Introduction

By Pamela Ayo Yetunde

The sankofa is a mythical bird of the Akan people in Ghana. It’s depicted with its head turned backward, pointing to the past, while the feet are turned forward, pointing to the future, and its body is centered in the now. This symbolism echoes Thich Nhat Hanh’s teaching that in the present moment we touch the past and the future.

The sankofa can be viewed as a symbol of resistance to the censoring of Black history in public education. The current attempts to whitewash curricula is anti-truth and therefore pro-ignorance. Why are some parents screaming at school board members, hounding educators from state to state, threatening librarians, and protesting the very existence of libraries under the anti-critical race theory rally cry? Why don’t they want students to know that Black people were enslaved and subjected to countless forms of cruelty between 1619 and 1865 in the U.S.? Why don’t they want students to know that Black people were relegated by law between 1877 and 1964 to live separately and unequally from white people? Why shouldn’t our future adults know the many ways apartheid, resistance to apartheid, and racist backlash to progress have been expressed in America?

Maybe this Black History Month we can ask ourselves, with our eyes looking back, feet facing forward, and body in the present moment, “Why are we so attached to a sanitized past?” and let the answers flow without judgment. This is a way we can embody the sankofa spirit.

Celebrating Black History Month must also include rejoicing in people who defied negative racialized stereotypes. Before he became the forty-fourth and first Black President, Barack Obama said we had to have “the audacity to hope.” Audacious confidence is what we need right now if we are to remember how Black people were punished just for remembering where they came from—punished for remembering the people they were separated from, for remembering their birth names, worldviews, cultures, their sense of self, their quest for freedom, and desire to love.

To embody the sankofa spirit—with our bodies in the present moment, looking back while moving forward—is the audacious confidence to dwell in the ultimate dimension, the timelessness of reality, so that a brighter future can be possible. History, if taught and taught factually, can protect future generations from repeating that history.

We’ve invited six practitioners from different traditions to reflect on a Black Buddhist ancestor in their tradition. All these ancestors are rather recent. Some are “hidden figures” to most readers. By paying homage to these Black Buddhist ancestors, we transgress the wave of ignorance and erasure. We embody the sankofa spirit.

Dr. Marlene Jones

By Ruth King

Dr. Marlene Jones and I met standing in front of a mammoth Buddha figure in Beijing during the World Conference on Women in 1995. We were two Black women with dreadlocks and flowing tears. In that moment, Marlene managed to ask, “Do you meditate?”

“Kinda,” I said.

Within a short time, we discovered we both lived in California’s Bay Area. She invited me to Spirit Rock, and my formal meditation practice began after hearing her teacher, Jack Kornfield, speak. I knew I was home.

For years, Marlene and I discussed racial ignorance in spiritual communities and our aspirations of healing the wounds dividing these communities. We shared how difficult it was to keep our hearts open and how much the dharma helped.

I remember the first time Marlene invited me over for tea. It was a lesson in presence. On that summer afternoon, her home in Sausalito was breezy and smelled of cinnamon. She’d soaked sliced red apples in lemon water, serving them on a plate accented with yellow rose petals from her garden. Sipping tea and eating apples, we talked at length about our children and mothers. We debated whether our service aligned with our hearts.

Dr. Jones was a trailblazer! She invited me to join Spirit Rock’s diversity council, which she created. At her request, I also attended the center’s first African American Meditation Retreat. And at her instigation, I was part of a small collective of women of color, which she organized along with Alice Walker; for ten years we met with Jack Kornfield to dwell in the dharma together.

Marlene was instrumental in creating the first daylong and residential retreats for people of color and the first diversity trainings at Spirit Rock. She influenced programing, staffing, and structures that supported inclusivity and equity.

Marlene passed away in 2013, surrounded by family, friends, and her beloved teacher Jack Kornfield. In those last moments of her life, when Marlene was gently asked to offer a sign of presence, tears began to roll down her cheeks. Hearing of this, I was reminded of the first time we cried together in the presence of the Buddha in China. I prayed that she was seeing the Buddha and once again offering her tears.

To most, she is remembered as a diligent practitioner and teacher of the dharma, a pioneer and visionary, a grandmother, educator, and devotee to justice. To me, she was all that. She was also a sister and a noble spiritual friend. Through her example, she ushered me into the dharma, showering me with care and understanding. May we all know intimately the power of spiritual friendship.

Ruth King is an insight meditation teacher and emotional wisdom author and life coach. Mentored by Jack Kornfield in the Theravada tradition, and influenced by the Tibetan traditions of Buddhism, Ruth teaches at insight meditation communities nationwide. She is a guiding teacher at Insight Meditation Community of Washington and Spirit Rock Meditation Center, and the founder of Mindful Members Insight Meditation Community of Charlotte. Ruth is the author of The Emotional Wisdom Cards, Healing Rage: Women Making Inner Peace Possible, and Mindful of Race: Transforming Racism from the Inside Out.

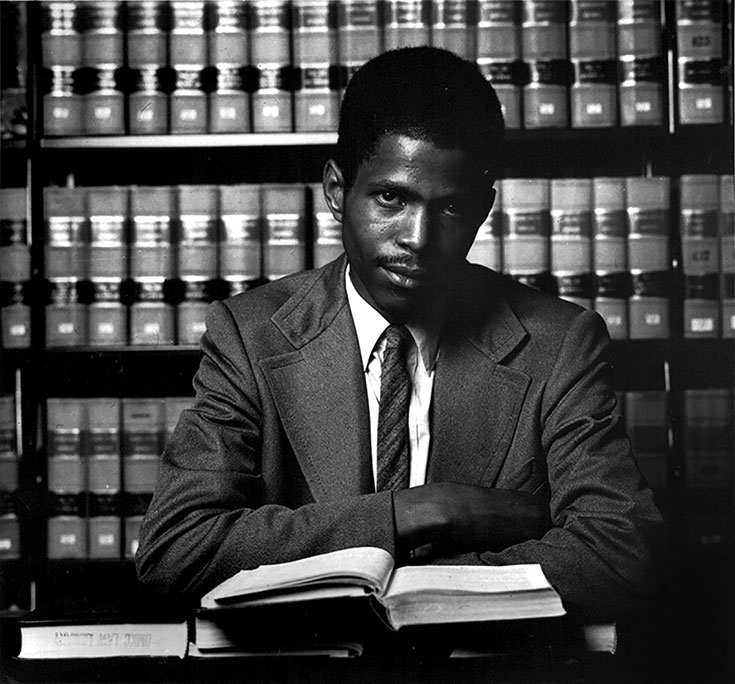

Alvin Sykes

By Dr. Kamilah Majied

How can Buddhism help someone who has endured deep suffering live in a way that brings justice to the lives of countless people? The life of prominent Buddhist activist Alvin Sykes offers a resounding answer to that question.

He was born in 1956 amidst brutally enforced racial segregation in Kansas City, Missouri. The difficulties in his early life included his fourteen-year-old birth mother conceiving him in rape, and his growing up in a group home, having epilepsy, and experiencing sexual assault himself.

At age eighteen, Sykes began practicing Nichiren Buddhism with the Soka Gakkai International (SGI) after he was introduced to the practice by his good friend, renowned jazz musician Herbie Hancock.

In the SGI, Sykes learned the practice of chanting Nam Myoho Renge Kyo to surface one’s inner wisdom, courage, and compassion in order to transform the painful circumstances of one’s life into something that creates value for oneself and others. This concept is known as “human revolution.”

Sykes was determined to address the violent racism affecting Black people and the lack of consequences for the offenders. In 1980, Sykes’s dear friend and noted saxophonist Steve Harvey was murdered and the murderer was promptly acquitted by an all-white jury. Sykes chanted about this and, with Hancock’s encouragement, decided to do something about it. He had no collegiate or formal education, but he didn’t let this stop him. Sykes pored over law books in the Kansas City library until he found a statute that could be used to reopen the case. Because of his relentless efforts, Harvey’s murderer was sentenced to federal prison and is still serving one of the longest sentences ever given for a civil rights violation.

This was just the beginning. Sykes went on to conduct more investigations into murders of African Americans that occurred throughout the sixties. Because of his decades of dogged labor, self-guided scholarship, and advocacy, the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act was enacted into federal law in 2008.

Sykes continued to advocate for victims even after being partially paralyzed from an injury in 2019. In a wheelchair, he said, “I am going to roll my way to justice.” Unable to grip a pen he used his voice and successfully advocated for legislation abolishing statutes of limitation on childhood sexual abuse.

Alvin Sykes epitomized what it means to take enlightened action in the service of others until the last days of his life. As we offer praise and blessings to his eternal life force, let us allow his example to guide us as we cultivate compassion, wisdom, and courage to positively impact all beings and the world we share.

Kamilah Majied, Ph.D. is a mental health clinician, educator and internationally engaged consultant on building inclusivity and equity using meditative practices. Dr. Majied is a social work faculty member at California State University, Monterey Bay. To learn more visit KamilahMajied.com

Roshi Merle Kodo Boyd

By Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao

Roshi Merle Kodo Boyd and I first met many years ago when we were both in Yonkers for a Zen program. Not long after that first meeting, Kodo asked me to be her Zen teacher. Having just received dharma transmission, I laughed it off and said, “I don’t know anything about teaching.”

“But you know how to be a student,” she replied. “That is more important to me.”

Due to her persistence, I became a Zen teacher. When Kodo began training, she was already a mature person with considerable spiritual instinct. According to her husband, Kodo came to Zen with “a clarity of thought and luminosity of perspective” honed from childhood discussions with her sociologist father and a deep determination to be “the best human being she could be.”

After years of Zen and koan training, I gave her dharma transmission, and she herself became a Zen teacher. Kodo’s gentle, unassuming manner belied a fiercely independent spirit and unshakeable resolve. I once asked her, “What is most important to you?” Without hesitation she replied, “Liberation.”

Whatever life served up—a chronic illness, intense inner struggles, a legacy of slavery—Kodo absorbed it into her vow to be free. Facing obstacles, she often quoted Zen Master Xuedou: “The dragon’s jewels are found in every wave.”

In 2011, Kodo took the abbot’s seat at the Zen Center of Los Angeles. The abbot’s seat is a training ground in endurance, complexity, and exposure. For those of us women who don’t readily claim the spotlight, it’s especially daunting. Kodo’s wisdom, humor, and great-hearted kindness was a balm for the sangha, and they responded in kind. “I felt so loved,” she said. The sangha as a force of love is one of her legacies.

Although we’re of the same White Plum lineage tree, Kodo and I had different flavors. This became especially evident one day while we were discussing which folktales best exemplified ourselves.

“I keep coming back to Goldilocks,” I said. “Particularly, ‘this one’s just right.’”

“Well, for me,” Kodo said, “I keep coming back to Baba Yaga, the wild woman who lived in a forest hut standing on chicken legs!”

That indomitable spirit is how I remember Roshi Kodo. It’s what made her a trailblazing, wild-woman Zen ancestor.

Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao is head teacher at the Zen Center of Los Angeles.

Rev. Dr. Leon E. Wright

By Aishah Shahidah Simmons

One of the “hidden figures” in Buddhist history is the Black scholar, theologian, author, and cultural attaché Rev. Dr. Leon E. Wright, PhD. In the 1950s, he studied in Myanmar with U Ba Khin, a leading twentieth-century authority on vipassana meditation. S. N. Goenka, who studied alongside Wright, later established meditation centers around the globe.

I practiced within the Goenka tradition for seventeen years. Yet, in all that time, I didn’t hear about Dr. Wright. How was an African American practitioner like myself never introduced to Wright’s legacy within this tradition? My puzzlement led me to investigate.

Born in 1902, Wright was a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Boston University where he also received a master’s degree in the history and philosophy of religion. Subsequently, Wright received a Sacred Theology degree in 1943 from Harvard Divinity School and a doctorate in 1945 in the History and Philosophy of Religion at Harvard University.

Then he joined the Howard University faculty in 1945 where he was the associate editor of the university’s Journal of Religious Thought. For his brilliant scholarship, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1952 and served as a cultural attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Yangon, Myanmar.

During his tenure as an attaché, Wright met U Ba Khin and studied with him extensively. The vipassana master once remarked that Wright could reach a state of deep reflection achieved by only one in ten thousand monks. Such was Wright’s aptitude and devotion that, in 1963, he became one of the first Westerners ever to be authorized by Khin. This authorization is an extraordinary historical example of a close connection between a Burmese Buddhist meditation teacher and his African American student. Khin did what it’s taken many white-dominant sanghas decades to do: authorize a Black teacher.

Authorization to teach lit a fire within Wright. Within three years he’d given dharma talks and taught meditation to many thousands of people. Yet Wright never identified as Buddhist, which is probably why his legacy in Buddhism remains obscure. He was a congregationalist minister who taught Buddhist meditation. As a Sufi Muslim-raised Buddhist practitioner, I resonate with how Wright’s Christian and Buddhist practices worked together.

Taking the cultural restrictions into consideration, I find it awe-inspiring that Wright, a Black congregationalist minister, taught Buddhist meditation during the reign of Jim Crow apartheid laws in the U.S. As a Black Buddhist, I am committed to placing Dr. Leon Wright’s name in the continuum of Westerners who studied Buddhist meditation in Asian countries and taught what they learned to their communities back home.

I first learned about Dr. Wright’s life from my dharma friend Joah McGee shortly after moving to Washington, D.C., the city where Dr. Wright lived and taught for most of his life. I believe my newly chosen ancestor waited on me, a spiritual descendent, to arrive so that I could meet him.

I speak your name, Rev. Dr. Leon Wright.

Aishah Shahidah Simmons (she/her), is a Buddhist practitioner in the Theravada tradition, and a trauma-informed Mindfulness meditation teacher. A Black feminist lesbian cultural worker, she is also the producer/director of the 2006-released, Ford Foundation-funded film, NO! The Rape Documentary, and the editor of the 2020 Lambda Literary Award-winning anthology, love WITH accountability: Digging Up the Roots of Child Sexual Abuse (AK Press 2019). (https://linktr.ee/afrolez)

Venerable Bhante Suhita Dharma

By Mushim Ikeda

Venerable Bhante Suhita Dharma was the first and possibly only African American to be monastically ordained in Mahayana, Theravada, and Vajrayana Buddhist lineages. He thus promoted what he called “the Triyana,” a blended Buddhism that was both fluid and deep, and he signed his letters, “Blessings of the Triple Gem.”

Born in the U.S. South during the Jim Crow years, Bhante Suhita’s Catholic monastic vocation was ignited by the racial violence he encountered. At around age seven, he and a friend were playing in a wooded area familiar to them when they came upon a Black man hung from a tree, horribly disfigured.

Reading Thomas Merton as an early teen, he felt a strong calling to join the Trappists. He became one of the last of the “child monks” to enter the Catholic Trappist order and was a Trappist for ten years. After Vatican II, he left the cloister and traveled throughout Asia where he encountered the buddhadharma.

Although Bhante Suhita held a plethora of monastic ranks and achievements by the time of his death in 2013, including being the equivalent of a bishop in the Vietnamese Buddhist Church in the United States, he had just as many friends, including several families whose children he befriended and mentored. As a spiritual friend, Bhante taught through example. During some periods he’d call me two or three times a week for casual chats, and at other times he’d be gone for months on pilgrimages to Buddhist and Catholic shrines and temples around the world.

Bhante was extremely fluid and demonstrated anatta, nonself, in his entire way of being; as a natural consequence of his practice, he manifested in dazzlingly different ways. He could look like a frail, frightened elder clutching his shoulder bag while waiting for a bus, then a moment later he could become a roaring dharma lion. He could be enjoying his favorite foods—fried chicken and ice cream—then a moment later he could answer a question in a quiet way that demonstrated his vast knowledge of Buddhism.

Near the end of his life Bhante said to me, “I’m transgender.” He said it two or three times in the same evening to make sure I heard. I knew that he had been raised by his grandmother, the matriarch of the family, who was called Big Mama by all and who protected and encouraged him. I always suspected that he channeled Big Mama through his mannerisms and the way in which he spoke.

Bhante delighted in being fluid in how he showed up in the world, yet was a very faithful, reliable friend. In other words, he was a one-of-a-kind person. He used to say, “What you see is what you get.” Then we would see so much and get so much.

Mushim Ikeda is a social activist and teacher at East Bay Meditation Center in Oakland, California. She also works as a diversity and inclusion consultant.

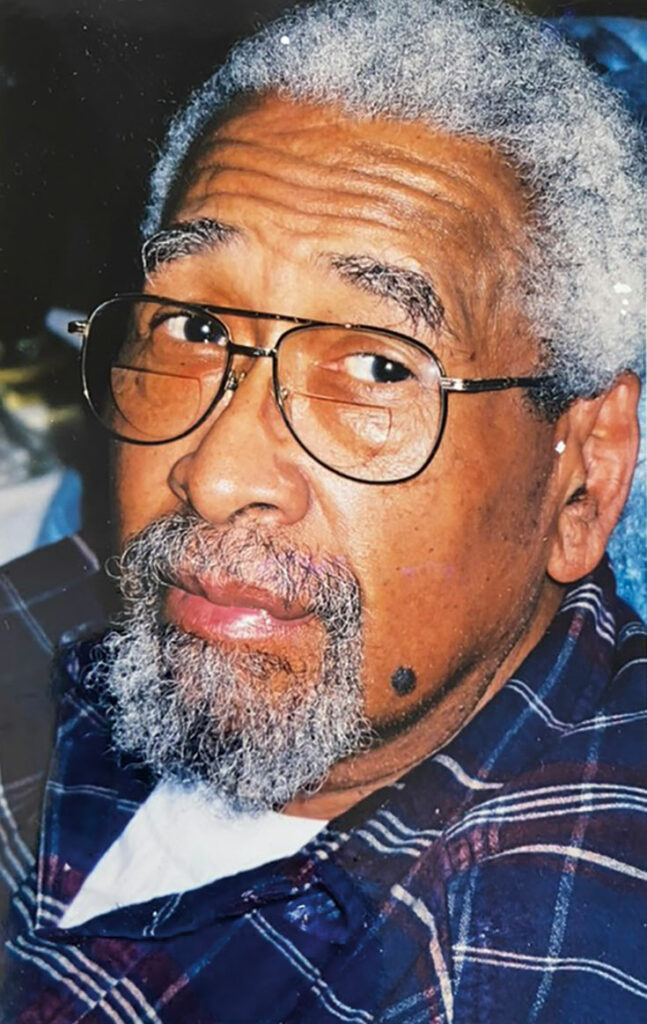

Leonard West

By Sister Peace

Born in 1935 in Oklahoma, Leonard West subscribed to many, seemingly disparate philosophies in his life. He was a jazz-loving beatnik in the fifties and a passionate “servant to the people” in the Black Panther Party in the sixties. Leonard also lived for seven years in Nara, Japan, where he was introduced to Buddhism, and proudly served in the U.S. Marine Corps in Korea and Vietnam.

Like so many who’ve experienced war, Leonard suffered an addiction to drugs. Thanks to his meditation practice and his wife, Bennie, he was able to transform his addiction and helped countless others to do the same. He became an activist in the recovery community, sponsoring scores of men as well as working as a counselor for fellow veterans.

Leonard created a diverse body of work—photography, paintings, drawings, sculptures, and assemblages. He exhibited in galleries and shows throughout the Southeast and taught at the Memphis College of Art and the Firehouse Community Arts Academy of the Memphis Black Arts Alliance, where he was a charter member.

Bennie pointed out to me, “Everything in his life impacted him and came through his art. The Black Panther party helped open his eyes and his heart to other truths. If you look closely at his art, you’ll see symbolism of the struggles of Black people and how we’ve overcome or succumbed in one way or another to issues of racism in this country.”

Leonard celebrated Buddhism in his art as well, assembling various images of the enzo, among others. Leonard formed the Magnolia Sangha in Memphis and in 2005 was one of the first African American practitioners to be ordained as a member of the Order of Interbeing in the tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh.

I asked Dr. Leslie Gordon, a fellow Memphian, his thoughts about Leonard, his dharma mentor. “Buddhism made a big difference in his life,” says Gordon. “It was one of the foundational supports he had in the recognition and transformation of his addiction and other suffering. It changed his perspective, and it changed his life.”

Leonard passed in 2011 after a long battle with colon cancer. Relaxing at home as his time approached, he was listening to Miles Davis’s “Round Midnight” when he slipped through the veil. And it was, indeed, around midnight.

Sister Peace is a nun in the Plum Village tradition. Recently, her service and practice have been focused on the children jailed in the Shelby County Juvenile Detention Center in Memphis.