This year we have all learned the lesson of impermanence. The plans we thought we were making, the lives we thought we were living—2020 has taught us just how illusory they were.

For many of us, jobs and careers have proven to be the most impermanent of all. Yet in these uncertain times of layoffs, furloughs, and unprecedented unemployment, it’s worth remembering this simple truth: You are not your job.

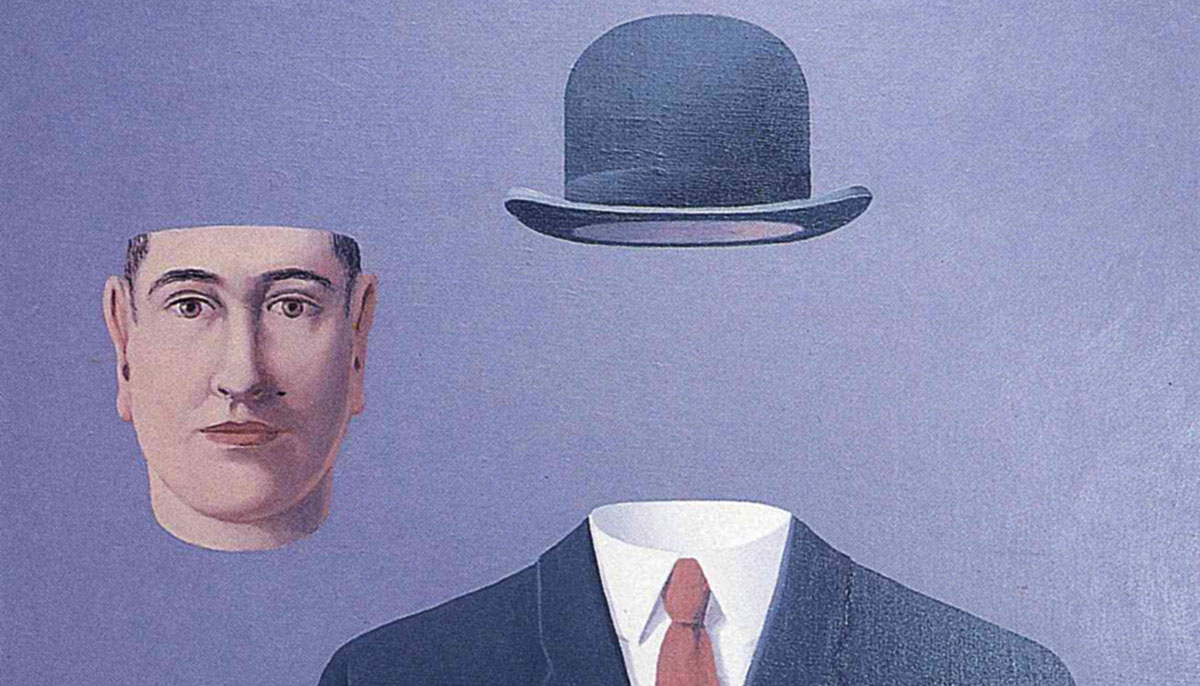

The Buddha might have taken that a step further. He might have said that you don’t exist at all, job or no job.

The plans we thought we were making, the lives we thought we were living — 2020 has taught us just how illusory they were.

To be clear, Buddha never said the world is a dream or that we’re all living in The Matrix. He didn’t mean nothing exists; he meant something a little subtler than that.

You can think of it this way: The physical body most people call you is real. If a basketball is hurled toward your head, it will bounce off and not pass right through. It’s more that this body isn’t really yours. Neither is anything else. And if there’s nothing that really belongs to you, then maybe there’s no you at all.

Imagine that you have a car and you replace one of the wheels. You’d probably say it’s still your car. What if you replace all four wheels? It probably stills feels like your car. But what if, overnight, someone replaced every single part of your car with parts from another car. Now what makes this car yours? Isn’t it more like a new car parked in the same space?

The concept of “your car” is just that—a concept, an idea. It’s not real in the deepest sense. In reality, there is no essential thing that constitutes your car. A Buddhist would say your car is empty—meaning not that it has no passengers, but that there is no essential thing within it that makes it yours.

Now reflect back on yourself five or ten years ago—or just back to the time before the current pandemic, which might feel like it was another lifetime altogether. Maybe you haven’t literally replaced any major parts, but still your body isn’t what it used to be. Perhaps your health has declined—or perhaps you’ve used your time in lockdown to get in better shape. Certainly individual cells have come and gone. The very atoms that make up the physical matter of your flesh and bones have been swapped with other atoms. Your memories are different. Your thoughts are different, too. Maybe you’re happier. Maybe you’re angrier. But one thing is certain—you’re not the same.

Now you’re faced with the same dilemma as with that car. If so many parts of you have changed, in what sense are you the same you? And if you’re not the same you anymore, maybe you were never quite you to begin with.

This is the essential paradox Buddha discovered—that people are “empty” in the same way as cars. Everything about us is changing all the time. And how could anything that is so subject to change constitute our essential self? Yet if there is no one unchanging thing that defines our true self, maybe there is no self at all.

Let’s bring this back to the world of work. Many of us feel defined by our work, by our careers. We define other people that way, too. The first thing we ask when we meet someone is often, “What do you do?” And yet our jobs are constantly changing, like parts of a car or cells in our body. Is anyone really doing the same work they did at the start of the year? The whole world has changed. Offices and businesses have closed, then perhaps reopened, and perhaps closed again. Jobs have disappeared. Companies have come and gone. Entire industries have been transformed. Is anything about work really the same?

The honest answer to “What do you do?” would be different every year, and certainly different today than it was a year ago. How could something that changes so often possibly define us?

Maybe you don’t quite accept Buddha’s teaching that there’s no you at all. That’s okay—it’s a strange and difficult concept, even for longtime Buddhists. But if there is an essential you somewhere that is constant across all the inevitable changes, it can’t have anything to do with your work. If whatever constitutes you can survive years and years of physical and mental change, it can’t possibly depend on something so variable as who issues your paycheck.

If you’ve been lucky enough to hold on to your job so far this year, that’s great. But you could still lose it tomorrow. Your company could still go under. Your boss could go crazy. You could even quit.

You are not your job. Whatever you are—you’re definitely not that.

If you’ve lost your job recently, this lesson is even more important. Losing a job is painful, and these are especially frightening times to be out of work. It’s natural to grieve that loss. But don’t let yourself forget what you haven’t lost. Whether you loved your job or hated it, don’t make it more than it was. It was a job. It wasn’t you.