If there’s a loose definition of what is Zen in this country, there’s an even looser definition of who is a Buddhist. I heard someone comment recently that you knew a person was Buddhist if they wore prayer beads around their neck or wrist. I’ve seen malas for sale in toy stores and in the twenty-five-cent vending machines in large chain stores and supermarkets. Being a Buddhist seems to be easy and “in” these days.

I’ve been wondering, though, if Buddhism were unpopular, or worse, if followers of the Buddha were persecuted, harassed, or imprisoned, how many people in America would still call themselves Buddhists? How many of us would risk chanting sutras or meditating if it became illegal? How many people would continue to wear malas if they became the modern Stars of David, reason enough to be beaten or put in jail? Under threat of execution, would we burn our Buddha statues and renounce our refuge in the triple treasures? This question reminded me of the story of a young woman whose small body was the vehicle through which Zen Buddhism entered Japan.

Her name was Zenshin. She was the first person to be ordained as a Buddhist in Japan. She was also the first Buddhist in Japan to be persecuted for her faith.

We don’t know very much about her. A brief account is preserved in the historical archive called the Nihongi. It relates that in 584, a young Japanese girl named Shima, daughter of Shiba Tatto, was ordained and received the Buddhist name Zenshin. She was eleven years old. Two other young girls were ordained at the same time. These girls, Zenzo and Ezen, may have been her friends or her ladies-in-waiting.

Why would an eleven-year-old girl ordain in a foreign religion? Perhaps she was being used as a pawn to cement alliances with the Buddhist countries of China and Korea or to increase her family’s social standing. It’s also possible that she herself was drawn to this exotic religion. Unfortunately, we have so few facts, we can only speculate.

Zenshin’s ordination occurred in the setting of intense political rivalry. The importation of Buddhism into Japan (via Korea) was opposed by two powerful and conservative clans: the Mononobe, who led the emperor’s military forces, and the Nakatomi, who were in charge of religious rituals of Shinto, the indigenous religion of Japan. The head of the rising and progressive Soga clan supported Buddhism, declaring, “All the countries of the west worship this Buddha. Why should Japan alone deny him?” Empress Suiko, granddaughter of Soga no Umako, offered her palace at Sakurai as a site for a Buddhist temple.

Zenshin’s father, believed to have been a Japanese diplomat to Korea, was close to Soga no Umako. Soga asked him and two other men to search in all directions for someone who practiced Buddhism. They found a Korean layman who had once been a Buddhist priest and an old Korean nun; together they were able to give initial instruction in Buddhist practices to Zenshin and her two friends.

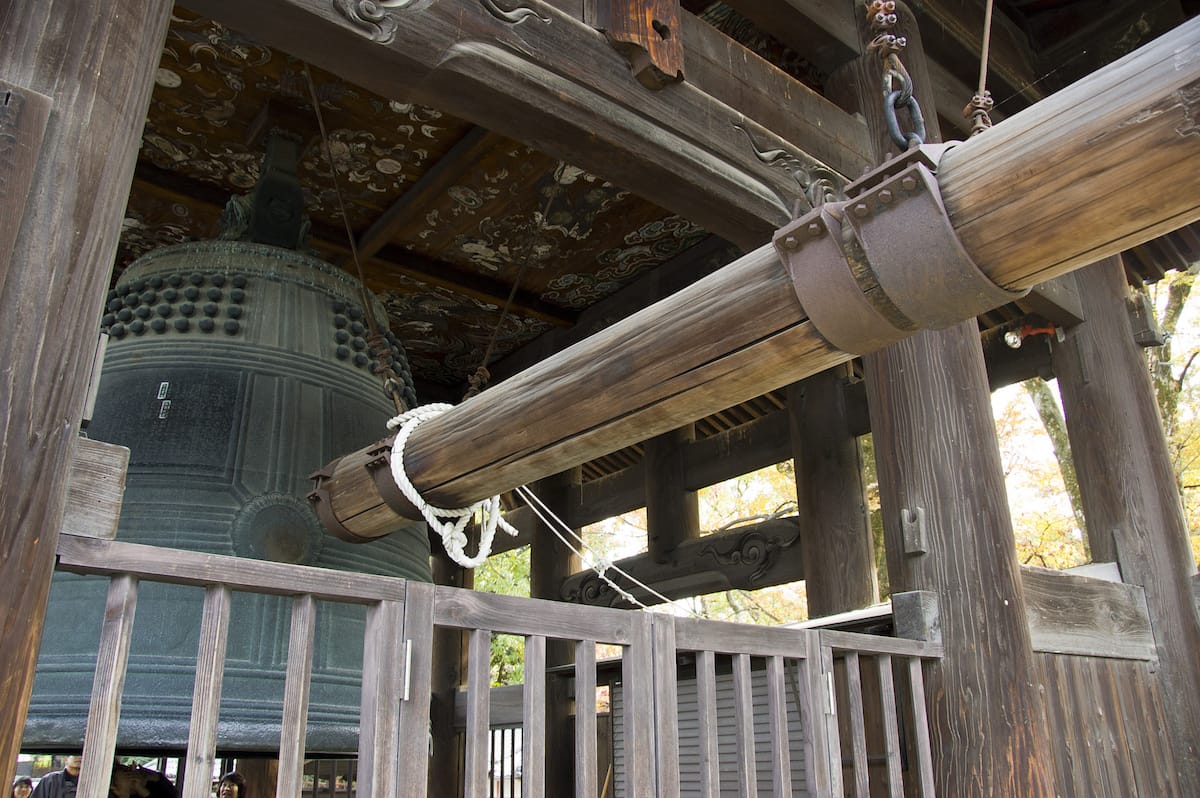

Soga erected a temple for the new nuns and enshrined a stone image of Miroku Buddha that he had requested from Korea. He also gave orders for the nuns to be provided with food and clothing. One day, Soga apparently witnessed a miraculous Buddhist relic that floated or sank in water upon command and that broke an iron hammer when an attempt was made to crush it. After that he became a fervent believer in the new religion, building a second temple in his own home.

Six months later an epidemic, probably of smallpox, swept through the land. Mononobe, arch rival of Chief Minister Soga, convinced the Emperor that the pestilence was due to the establishment of Buddhism. Mononobe destroyed a pagoda Soga had built, set fire to the nuns’ temple, and took the remains of the Buddha statue and flung it into a nearby canal. He summoned the three nuns, stripped them of their robes, and had them flogged and imprisoned.

Over the next three months of summer heat, the epidemic grew worse, and even the emperor fell ill. Dying people cried out that their bodies felt as if they were on fire, and that this must be retribution, punishment for the burning of the Buddha image. Soga again addressed the emperor and begged to be allowed the succor of the three treasures. The emperor decreed that Soga alone could practice Buddhism. The three nuns were released into his care and he rebuilt their temple. That autumn the emperor died, but Buddhism did not.

Zenshin and her nuns continued to practice, and two years later, in 586, they asked permission to go to Korea to be fully trained in the precepts. They returned to Japan as fully ordained bhiksunis after three years, whereupon many other people undertook ordination and many Buddhist temples were built. A year after Zenshin had left for Korea, the Mononobe clan was defeated in battle and subsequently annihilated. Zenshin returned to a country that was ready, with the encouragement of Empress Suiko, to embrace Buddhism. Within four decades there were 569 nuns and 816 monks in Japan.

No matter what the reasons for Zenshin’s ordination—whether she was a reluctant nun, a political pawn, a rebellious teen, or a vestal virgin—something happened to transform her. Somehow during the time the girls were training with the old Korean nun, in those few months that they were able to practice before the tides of public sentiment turned, the practice “took.” It took firmly enough to sustain them through the terror of the destruction of their temple, the humiliation of being stripped and flogged, and the misery of their imprisonment.

Perhaps this is the test of who is a Buddhist, a person who practices in the good times so that they can take refuge in the practice in the bad times, when the need is urgent. It is inspiring that a girl, a child, found this fearless center for herself, in an environment steeped in political intrigue and marked by the assassination of entire families.

Zenshin’s life also tells us that the effects of one person’s practice should not be underestimated. It can catalyze the transformation of an entire country. It can last for thousands of years, through all the ups and downs of human fortune and whim. I thank this earnest child Zenshin whose sincere practice has brought the happiest gift, the gift of dharma, to us today.