Somewhere in the soil of California’s Central Valley lies buried treasure. Scholar and Soto Zen priest Duncan Ryuken Williams tells the story of ten-year-old Masumi Kimura and her family. Like many other Japanese American families living in California before World War II, the Kimuras were farmers, tilling soil and developing irrigation systems for land that had long been dismissed as inarable by white Americans. They were also Buddhist, part of the earliest organized Buddhist community in America. Because of their ethnic and religious background, especially Mr. Kimura’s leadership role at the local temple, the family was deemed suspect by the FBI following the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Williams details the day that Masumi came home “to find her father pinned on the ground and an agent holding a gun to her mother’s head.” After further questioning by the FBI, the agents left. Mr. Kimura, anxious to protect his family from further violence, instructed Masumi to prepare a fire in the bath furnace. He gathered all of the family belongings that had Japanese writing or any trace of Japaneseness and threw them into the fire. “However,” Williams writes, “her father hesitated with a few items.”

Masumi remembers that her father set aside minutes from board meetings and other temple documents from the Madeira Buddhist Temple, the family’s bound edition of the Buddhist scriptures…Wrapping the Buddhist scriptures and the temple records in the kimono cloth and placing them in the tin boxes, Masumi’s father carefully lowered them into the hole and covered them with dirt. It was safer to bury these items than to keep them. -“Lessons from the Internment of Japanese-Americans,” Dharma World Magazine

Given the hostile anti-Japanese sentiment sanctioned by the federal government, the Kimuras were left with little option but to burn or bury any signs of their spiritual and cultural difference.

The Kimura family’s experience demonstrates merely one historic example of the ways in which Asian and Asian American Buddhists have long been viewed with violent suspicion for our cultural and spiritual differences. Though our communities are diverse and complex—including Central Asians, South Asians, Southeast Asians, East Asians, and Pacific Islanders—our experience of exclusion in regard to the representation of our spirituality is shared. For Buddhists of Asian ancestry living in the United States, being Buddhist has historically been tied to racial assumptions that have marked us as “perpetually foreign.” These differences have been used to systematically violate our civil rights and exclude us from society in significant ways.

Undeniably, America has been created by excluding people whose differences were deemed inferior—a process known as racial othering—so as to establish a seemingly natural superiority of white people.

White supremacy, the system of power behind the suspicion and exclusion of Asian and Asian American Buddhists, is the same system that justified the founding and building of the U.S. through the genocide of indigenous peoples and the labor of enslaved Africans. Undeniably, America has been created by excluding people whose differences were deemed inferior—a process known as racial othering—so as to establish a seemingly natural superiority of white people.

White supremacy has systematically alienated Asian and Asian American Buddhist communities and diminished the validity of our relationship to Buddhism in the U.S. The erasure and exclusion of our communities is not merely about a lack of inclusion; to put it so simply would be dismissive of the facts of history. The exclusion of Asian and Asian American Buddhists from conversations on American Buddhism is cultural appropriation. It renders invisible our foundational role in establishing and maintaining Buddhism in America despite white supremacy. Thus, such erasure denies our right to claim our deep and specific connection—indeed, our centrality—to American Buddhism. It appropriates our historical authority in order to promote the white ownership of an indigenous Asian practice for liberation.

The same process of white supremacy has created an American culture in which other practitioners, namely white practitioners, have been granted the freedom to be Buddhist in safer and more public ways. Moreover, instead of facing systemic injustice for embracing a spirituality that departs from the Judeo-Christian norm, white Buddhists are often lauded for this difference. They may attain a certain cultural capital for their practice, for donning Buddhist symbols and using dharma names in Asian languages, all of which mark them with distinction as “interesting,” perhaps even “worldly”—anything but “suspect” or “foreign.”

This is white supremacy and privilege in Buddhism.

The white ownership of Buddhism is claimed through delegitimizing the validity and long history of our traditions, then appropriating the practices on the pretext of performing them more correctly.

Most conversations about cultural appropriation in Buddhism revolve around the outward symbols and signs of the practice: beads, tattoos, statues, and so on. But an important element of the appropriation occurs through the assumed occupation of white authority status, often legitimized through the intellectual study of Buddhism. In a Fall 2000 special issue of Turning Wheel: The Journal of Socially Engaged Buddhism dedicated to addressing the underrepresentation of “Buddhists of Asian Descent in the U.S.,” guest editors Maia Duerr and Mushim Ikeda shared the following reflection:

Not long ago, a prominent European-American Buddhist related that during a trip to Japan, she discovered that she knew more about Zen than most Japanese. This innocent remark reflects some all-too-common perceptions often held by non-Asian Buddhists: that they are “more knowledgeable” about Buddhism, that they practice “real” Buddhism, as opposed to “folk” Buddhism.

Indeed, Asian and Asian American Buddhist practices have often been dismissed as superstitious, inauthentic (yet authentically exotic!) forms of Buddhism. In mainstream white American Buddhist conversations, white Buddhists are often heralded as the erudite saviors and purifiers of Buddhism. This perspective exemplifies the subtle enactments and overwhelming hubris of white supremacy. In positioning a certain type of Buddhism (white) as better than other kinds of Buddhism (Asian, “folk,” “baggage Buddhism”), the white ownership of Buddhism is claimed through delegitimizing the validity and long history of our traditions, then appropriating the practices on the pretext of performing them more correctly.

The assertion of white authority goes hand in hand with the mainstream erasure of the contributions of Asian and Asian American Buddhists in the development of Buddhism in the U.S. Perhaps the most public example of such erasure was demonstrated in the in the early 1990s when Tricycle editor Helen Tworkov stated, “The spokespeople for Buddhism in America have been, almost exclusively, educated members of the white middle class.… Asian American Buddhists … so far … have not figured prominently in the development of something called American Buddhism.” Rev. Ryo Imamura, an 18th-generation Buddhist priest in the Jodo Shinshu tradition, responded with a letter to the editor:

I would like to point out that it was my grandparents and other immigrants from Asia who brought and implanted Buddhism in American soil over 100 years ago despite white American intolerance and bigotry. It was my American-born parents and their generation who courageously and diligently fostered the growth of American Buddhism despite having to practice discretely in hidden ethnic temples and in concentration camps because of the same white intolerance and bigotry. It was us Asian Buddhists who welcomed countless white Americans into our temples, introduced them to the Dharma, and often assisted them to initiate their own Sanghas when they felt uncomfortable practicing with us…

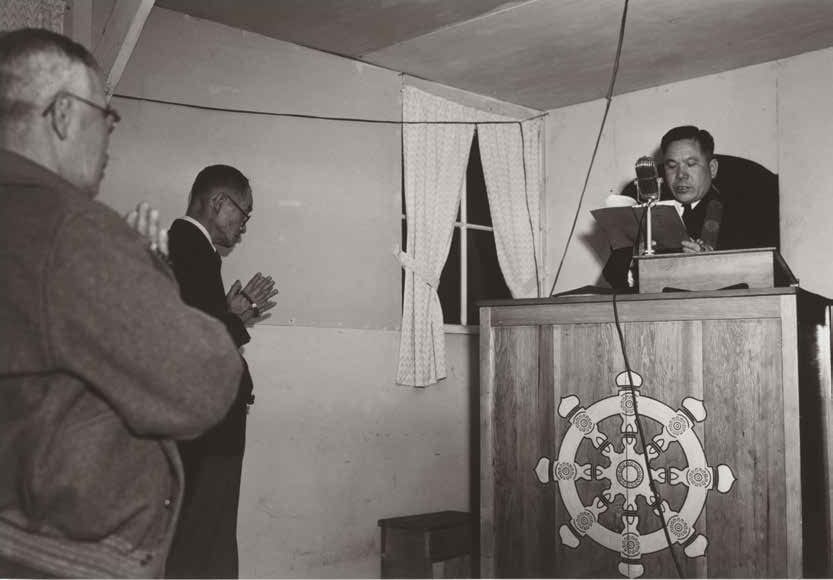

Rev. Imamura was speaking from a particular place, that intersecting space of being Asian American and Buddhist in a country maintained by white domination. He was born during World War II in the Gila River incarceration camp in Arizona. Like the Kimuras and more than 120,000 other Japanese Americans on the West Coast, the Imamuras were forced into barren camps because of the “suspicious” nature of their culture and spirituality. Behind barbed wires, in the face of constant threat by armed sentry, the Imamuras persisted in their Buddhist practice. They continued to aid other members of their community on their path of liberation from suffering, especially the daily suffering of incarceration and white domination.

This was their American Buddhism.

Rev. Imamura was also speaking quite literally. After their incarceration, his father and mother, Rev. Kanmo and Jane Imamura, established the Buddhist Study Center of Berkeley, where they hosted eminent teachers and welcomed Asian, Asian American, and white practitioners alike. Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, and Alan Watts were among the “countless white Americans” who learned about Buddhism from their study groups. The lectures and events were all free of charge, including the hot tea and pastries set out by Jane Imamura to welcome the attendees. It is important to note that Jane’s father, Rev. Issei Matsuura, was one of the first Buddhist priests to be arrested by the FBI and imprisoned at the start of World War II. As a priest, he was viewed as an especially dangerous threat to national security. That the Imamura family would go on to openly and freely share the buddhadharma in America after being imprisoned by the U.S. government for their cultural/spiritual beliefs is a notable example of the ways in which Asian American Buddhists have labored to maintain their practice and make it available to others, despite white supremacy. Yet the Imamuras’ historical contribution in cultivating a new generation of American Buddhists—including white Buddhists—were left out of the mainstream conversation on Buddhism. Rev. Ryo Imamura’s letter was rejected from Tricycle and never published.

[May, 2017 update: Noting Rev. Imamura’s request upon sending his letter — “Please do not reprint this letter in Tricycle if you do not print it in its entirety” — Funie Hsu and Buddhist Peace Fellowship have now reproduced it online, writing, “25 years later, the Buddhist Peace Fellowship is honored to be able to publish the letter in its complete, uncensored form. […] By making the full letter available online, we hope to spark conversation and enable Asian American Buddhists to find community and know, in the epistemological sense, that we have always existed. And that we have resisted.” Read it here.]

This is but one example of the ongoing reality of Asian and Asian American Buddhist erasure. It is evident that the cultural appropriation of Buddhism operates on a framework that holds that our spirituality can only be made safe through white ownership.

To be clear, Buddhism belongs to all sentient beings. Even so, Asians and Asian American Buddhists have a rightful, distinct historical claim to Buddhism. It has been rooted in our cultures for thousands of years. When it is said that Buddhism has been practiced for over 2,500 years, it is important to consider who has been persistently maintaining the practice for millennia: Asians, and more recently, Asian Americans. It is because of our physical, emotional, and spiritual labor, our diligent cultivation of the practice through time and through histories of oppression, that Buddhism has persisted to the current time period and can be shared with non-Asian practitioners. This is historical fact.

Everyone can benefit from reflecting on cultural appropriation as a way to deepen our Buddhist practice. We can do this by using the five precepts as a guide.

To not acknowledge the labor and contributions of Asian American Buddhists in the development of American Buddhism is simply cultural appropriation.

Everyone can benefit from reflecting on cultural appropriation as a way to deepen our Buddhist practice. We can do this by using the five precepts as a guide. One teacher I study with stresses that the precepts are not merely about refraining from certain actions (no killing, no stealing, and so on); equally as important, they are about proactive efforts we can take to foster our spiritual development. The precept directing no stealing, for example, should be understood as both not taking what is not yours or what is not freely given and as actively practicing dana, or generosity. We can apply this approach to the issue of cultural appropriation.

In order to alleviate the suffering caused by cultural appropriation, we can refrain from asserting ownership of a free teaching that belongs to all. We can refrain from asserting false authority and superiority over those who have diligently maintained the practice to share freely with others. And we can actively work to give dana by expressing gratitude for the Asian and Asian American Buddhists who have shared their indigenous ways of being as integral expressions of their practice.

For white practitioners in particular, you can also mindfully investigate the emotions that arise when issues of cultural appropriation are brought to your attention.

We can reflect on our tone in speaking about our knowledge of Buddhism and our relationship to it. We can ask two simple questions: First, am I asserting a sense of superiority over others, especially Asian and Asian American Buddhists, with my Buddhist practice? And am I using my Buddhist practice as a source of special distinction?

For white practitioners in particular, you can also mindfully investigate the emotions that arise when issues of cultural appropriation are brought to your attention. Robin DiAngelo writes about the concept of “white fragility,” a set of emotions—including anger, defensiveness, guilt, and more—that often accompany the thoughts of white people when they are forced to confront the reality of white supremacy. This concept can be helpful for white Buddhists in thinking about the false self and possible attachments to protecting the ego. Deep contemplation on this can help shatter the fragility of the false self and the delusion of racial colorblindness.

Dana as gratitude might include intentional efforts to center the histories of Asian and Asian American Buddhists in your sanghas; that work might be informed by facilitating reading groups or inviting Asian American Buddhist scholars and practitioners to speak. A white practitioner could choose to attend an Asian-dominant sangha and learn from a teacher who is not white. And we can all actively assert the need for consistent incorporation of Asian and Asian American Buddhist perspectives and leadership roles in popular Buddhist magazines, organizations, and conferences.

Advocating for the centrality of Asian and Asian American Buddhists is definitely not to say that we practice the most authentic, perfect form of Buddhism; in fact, a different form of racism can also exist in Asian sanghas, one that’s directed at non-Asian People of Color. Dana, then, might also look like a mutual fostering of conversations about how we can combat interpersonal racism toward each other in our communities and sanghas. Recently, a few members of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship have begun to initiate such conversations as part of what the organization calls Radical Rebirth—a set of guiding principles that have restructured BPF’s work to mobilize against systemic oppression, grow compassionate direct action, and actively seek racial justice, among other engaged projects.

Finally, for those of us who are Asian or Asian American, we, too, must examine our role in other forms of cultural appropriation. It is not enough to argue for our centrality in American Buddhism. We have an obligation to examine our own participation in white supremacy in all areas of our lives. We must have conversations in our sanghas about actively supporting our dharma family of color, especially when the violent suffering of Black Americans continues to be so blatant.

Though the Kimura family’s treasure has now been lost to the soil of the earth, the historical context of its burial illuminates the brilliance of the triple gem (Buddha, dharma, and sangha) as a path for liberation. In the U.S., that path includes the liberation of suffering from white supremacy. This is American Buddhism.