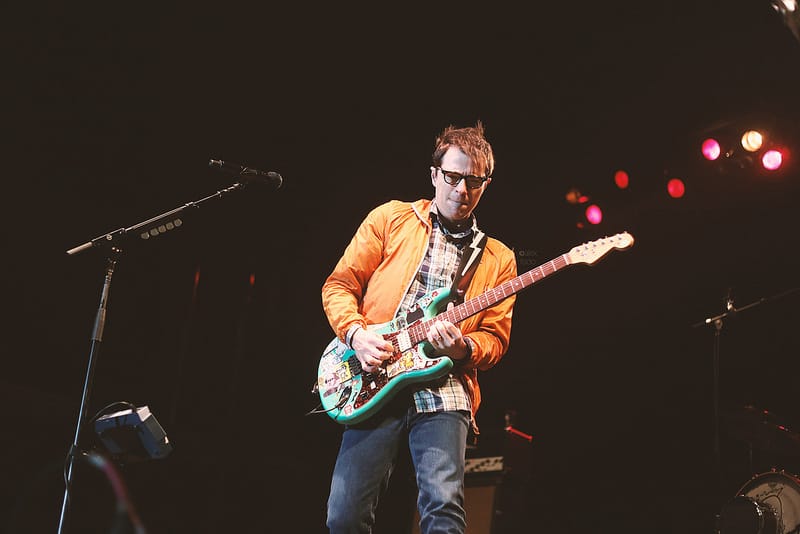

Though I know it’s a pipe dream, I still fantasize about being a rock star. Making millions of dollars, recording platinum-selling albums, and playing to stadiums filled with thousands of screaming fans sounds like the ideal life to me. But, after talking to one of the musicians I admire—Rivers Cuomo, the lead singer and guitarist for the band Weezer—I’m not so sure. His rock star experience was far from magical; that is, until he discovered meditation practice.

Being a music fanatic and a drummer, I was first introduced to Weezer not long after they became well-known in 1994. I was in high school at the time and, I have to admit, I was a geek. Sure, like most Canadian jocks I played high school hockey, but I definitely didn’t fit in with the popular kids at my school. Socially disenchanted, I found that Cuomo’s lyrics spoke directly to me. Weezer filled the musical void created by the death of Kurt Cobain and the end of Grunge. With simple and driving rhythms, fragile vocals, and distorted harmonics, they mixed the best of pop and grunge. They were, and still are, the gods of geek rock, and their songs have become anthems for the alienated, awkward, and lonely. Their platinum-selling self-titled debut, dubbed the “blue album,” was never far from the CD player at any party I attended.

This year Weezer released its fifth album, Make Believe. It has not only received approval from music critics, getting four stars out of five from Rolling Stone, but has also been selling well, reaching the number two spot on the pop charts in its first week of sales. Cuomo credits the success of this new album, in part, to his growing involvement with meditation practice. Although he was introduced to meditation as a child, it wasn’t an important part of his life until the rigors of the music business sent him looking for a way to deal with the obstacles he was facing.

Rivers Cuomo’s parents met at the Rochester Zen Center and the family moved to Yogaville, Swami Satchidananda’s Ashram in Pomfret, Connecticut, when Rivers was five. The community’s private school was non-sectarian and learning about different religions was part of the curriculum. There were also no divisions between grades, with students of all ages and backgrounds learning together. Cuomo recalls the experience as overwhelming. “We practiced hatha yoga and meditation every day as part of the school. I didn’t really enjoy it. I was a kid and I just wanted to go outside and play tackle football,” he says.

Despite his reservations about the school, it helped to him to cultivate an inquiring mind and set clear goals in his life, and from an early age musical success was one of his goals. He began by playing Kiss covers with neighborhood friends and later formed a band called Avant Garde. The band played progressive metal, a style mixing complex compositional structures and odd time signatures with the intensity of heavy metal. Avant Garde performed several shows in Connecticut before moving to Hollywood in 1989 with dreams of major music success.

Avant Garde broke up not long after moving to Los Angeles, and Cuomo formed Weezer in February, 1992. The band signed with Geffen Records in June, 1993, and began recording the blue album that August. The album’s songs “Undone—The Sweater Song,” “Buddy Holly,” and “Say It Ain’t So” became hit singles and brought Weezer success, fame, and fortune. But their 1996 follow up, Pinkerton, bombed commercially and was panned as the worst album of the year by Rolling Stone. The band went on hiatus until 1999, when they began playing concerts again and working on a new album. Released in 2001, Weezer’s self-titled third album is popularly known as the “green album.” With the catchy singles “Hash Pipe” and “Island in the Sun,” the album helped the band to recapture much of the fan base it had lost.

At that point, Cuomo began to manage the band himself. Though he recalls the experience as exciting and empowering, it began to cause problems in his life. “The band was like a totalitarian regime,” he admits. Influenced by the philosophy of Nietzsche and his concept of the superman, Cuomo believed that, by nature, it was his prerogative to prevail over other beings and achieve as much as possible. Ironically, he found that this outlook choked his creativity to the point where he was unable to achieve anything. As his creativity started to dry up, he became fearful, paranoid, and angry. Weezer’s success had gone to his head. “I started to think, ‘Now I’ve got to maintain my success. What if my next song isn’t as good? What if my next album isn’t as good?’”

The band’s fourth album, Maladroit, was a flop. Though he was living a life of opulence, with assistants to cater to his every need, Cuomo hated himself and the music he was making. Selling his house in the Hollywood Hills and his collection of Spanish Colonial furniture, he moved into a small, empty apartment with just the essentials. “My life had gotten very complicated. At the time I thought I had to deprive myself and suffer so that I could get in touch with my creativity again. Looking back, I don’t think I needed to experience that deprivation to pull myself out of the place I was in,” he says. “I’m not proud of that, and I certainly don’t endorse jumping from one extreme to the other.”

In many ways, however, it was Cuomo’s discombobulated state of affairs that opened the door to meditation. He was now willing to try something radically different, something that could help him get back in touch with his creative side and push him to be not only a better artist but a better human being. In March, 2003, Rick Rubin, who produced Weezer’s current album, suggested Cuomo try meditation to help bring balance to his life. “Before I started meditation I was extremely skeptical and even fearful that it was going to rob me of the angst that I felt was necessary for my songwriting,” Cuomo says. “I committed to sit once and if I felt like it was making me too numb or spaced out, I was never going to sit again.”

That first meditation session did not space him out. Instead, it helped to loosen the grip of his self-defeating attitude. With more meditation practice came less internal criticism. “I was in such an agitated place that even just sitting once, I could see the benefits,” he says. “I got up twenty minutes later and I was like, ‘Woah, I feel calmer and that’s a good thing.’” Though he had not completely recovered from his intense anxiety, Cuomo knew he was moving in the right direction.

After looking at a number of different Buddhist sites on the internet, he came across www.dhamma.org, the website of vipassana meditation teacher S.N. Goenka. Goenka teaches a non-sectarian practice that focuses on close attention to every sensation. It’s a simple but very powerful method of meditation that has helped people from many different religious traditions and walks of life. Goenka’s approach does not include ritual, clergy, or hierarchy, and in fact he believes it should not even be called Buddhism. As Goenka’s teacher, U Ba Khin, taught him, the Buddha taught only sila (morality), samadhi (concentration), and prajna (wisdom) and nothing needs to be added or subtracted.

At a time when religion and spirituality have become a fashion statement for many stars, Cuomo had chosen a difficult and serious path where he could, he says, “do some serious work on myself.” Goenka teaches vipassana through rigorous ten-day courses. Students take precepts to abstain from harming living beings, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, and taking intoxicating drugs or drink. They get up at 4 a.m. and eat only tea and fruit for supper. Among the many hours of meditation, the course includes hour-long “strong determination” sessions, in which participants are to move only when it is absolutely necessary. The goal of this style of meditation is “purifying your mind of all the anger, and all the sadness, and all the hatred, all the lust, all the fear, all the worry,” says Cuomo. “That’s what I’m aiming for, total purification of the mind.”

Cuomo’s first ten-day retreat had a profound effect on him—he has done seven more since. He believes that attending Goenka’s courses and practicing two hours each day has helped him to become more happy and aware. For one thing, he now views his success differently. “Before meditation,” he reflects, “I was looking at fame and wealth as the goal of my life.” This left him feeling empty and disillusioned. By learning not to strive for fame and wealth, Cuomo feels, ironically, that he has achieved more of it than he otherwise would have. “After practicing meditation for a while and listening to Goenka speak, I’ve come to see the dangers of accomplishment, success, fame, and wealth,” suggests Cuomo. “While there are good points to that kind of success, Goenka recommends that you give back a portion of your income, or give time to centers, serving so that other people can meditate, and view your efforts as benefiting not just yourself but everyone else. This helps dissolve your ego even as you become more famous, even as you make money.”

Cuomo also relates differently to his band, and the rifts between band members that once threatened to destroy Weezer are slowly being healed. Over the years, the band has had many internal disputes, with members threatening to quit and going for long periods without talking to each other. When the band made the cover of Rolling Stone on May 5 of this year, their bassist, Scott Shriner, told the magazine, “I’ve been in bands where even if you’re in the middle of nowhere with a broken-down van, you laugh your guts out and puke all over each other. That’s not Weezer.” Cuomo feels his meditation practice is now helping to create a more harmonious relationship between members. “I no longer vacillate between the extremes of being a dictator and telling the guys exactly what they have to play or, on the other hand, shutting down and being totally passive and saying ‘Play whatever you want; I don’t care.’” By letting go of his fear, he has become more willing to discuss the direction of Weezer’s songs with the rest of the band. “I can collaborate and discuss and say, ‘Hey, that sounds cool; why don’t you try it a little more like this?’ and I can take criticism from them. They might say, ‘Hey, why don’t you sing it like this?’ and I don’t get angry at them. It’s much more comfortable to be in this band. It’s much more comfortable to be alive now.”

Cuomo believes that he has changed as a musician as well, and that you can hear it on Weezer’s last two albums. “If you compare the songwriting and the singing on Maladroit and Make Believe, you can hear a huge difference in how present I am,” he suggests. “My voice is so much more expressive and in touch with my emotions now than it was before.”

Cuomo thinks that most people, even artists themselves, don’t realize how important concentration is in creative work. In order to create, he feels, the artist must be able to overcome external distractions and, more importantly, internal distractions such as self-doubt or praise. These internal distractions can easily derail the songwriting process; without concentration the artist may focus on the thoughts that arise when creating, rather than on the creative drive itself. “When you get really excited or agitated, when you’re thinking you’re so great or hot or whatever, you don’t realize that the line you just wrote maybe isn’t all that great,” he says. “Maybe you could’ve gone a little deeper and discovered something more profound to say.” He feels meditation has allowed him to quiet that internal chatter, clearing a path so he can move closer to the heart of his creativity and figure out exactly what he wants to say.

Cuomo feels that a lot of popular music draws on negativity for inspiration, just as he once relied on anger and sadness as the source of his creativity. His reliance on negative energy for creativity has dwindled with the help of meditation. “I would concentrate my mind by focusing on some really intense emotion within me,” he recalls. “I would be overcome by that emotion, allowing me to block out the internal chatter. While that worked temporarily, those emotions come and go and as you get older they’re not as intense or reliable. In any case, it’s not a good life if you’re constantly trying to dig up those intense emotions and cultivate all that negativity within yourself. Who wants to live like that? Even if it means you can write songs off of it.”

Though he has been a seeker his whole life, Cuomo is careful not to use the word “spiritual” to describe his search for meaning. He claims it’s difficult to say exactly what spirit really means and believes a more accurate description of his quest would be “artistically searching.” The key to this search is the investigation of his mind, observing how it works. Cuomo feels that by exploring his own mind, the insights he gains will not only help him to create better music but also to become a better human being.