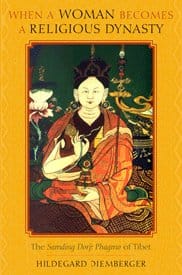

When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty: The Samding Dorje Phagmo of Tibet

By Hildegard Diemberger

Columbia University Press, 2007

416 pages; $49.50 (hardcover)

When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty lives up to its intriguing title by recounting the tale of Chokyi Dronma, the Princess of Gungthang, who became an inaugural figure in the oldest female incarnation line in Tibet. A complex and multifaceted persona, Chokyi Dronma (1422–55) was a princess, a fully ordained nun, a lineage holder in the little-known Bodongpa tradition, an avid patron and organizer of Buddhist construction projects, and possibly the consort of several important tantric masters of her time. But more importantly, for the longevity of her line, she was recognized as an incarnation of the female tantric deity, Vajravarahi—or, in Tibetan, Dorje Phagmo—imbuing her life and deeds with special sanctity. Though Chokyi Dronma died at the early age of thirty-three, her legacy continued in the formation of one of the few female incarnation lines in Tibetan Buddhism, the Dorje Phagmo line, later associated with Samding Monastery. So highly esteemed was the Samding Dorje Phagmo that Sir Charles Bell, an early Tibetologist and influential British officer in colonial India, dubbed her “the holiest woman in Tibet.”

In When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty, Hildegard Diemberger reconstructs the life and times of Chokyi Dronma and also tracks the fortunes of her successors in a continuous line of reincarnations up to the present. The first half of the book examines the complexity of Chokyi Dronma’s identity, the gender-related challenges she faced, and her wide-ranging activities and accomplishments. In addition, Diemberger provides a lucid translation of Chokyi Dronma’s recently discovered biography (a rare manuscript found by Leonard van der Kuijp in a Beijing archive), unencumbered by annotations, which the author is reserving for a specialized publication. The second half of the book addresses the lives of Chokyi Dronma’s subsequent incarnations, the establishment of the Dorje Phagmo seat at Samding near Yamdrok Lake in southern Tibet, and the life of the current Twelfth Dorje Phagmo. Sadly, the current incarnation in the Dorje Phagmo line, who is a top government official in the Tibetan Autonomous Region, recently defended the Chinese takeover of Tibet and publicly criticized the Dalai Lama.

In recounting Chokyi Dronma’s tale, Diemberger conjures the arid, rugged landscape of southwest Tibet alongside the intrigues of Gungthang and neighboring kingdoms. This was a turbulent time in Tibetan history as factions vied for power in a vacuum left by the demise of the Sakya hegemony, a century prior to Chokyi Dronma’s birth, and Diemberger argues that the “fluidity of the political landscape” had an important bearing on religious life. In language accessible to the non-specialist, Diemberger provides a rich historical account, based on her extensive travels in the region and meticulous research utilizing royal genealogies, the biographies of contemporaneous figures, and regional histories. To help the reader imagine Chokyi Dronma’s world, the book also includes sketches of important sites in southwest Tibet and a robust sixteen-page insert of photographs capturing murals, sacred sites, structures, and people connected with the Dorje Phagmo line.

Diemberger is sensitive to the constraints Chokyi Dronma faced as a woman as well as her unique opportunities as royalty. Due to the importance of marital alliances between petty kingdoms, Chokyi Dronma had a difficult time escaping married life and managed to become a nun only under drastic circumstances. After the death of her first daughter in infancy, Chokyi Dronma cut off her hair in a frenzy and—disheveled and bloody—confronted her in-laws, the king and queen of southern Lato, who in a state of shock agreed to let her go. Once freed from married life, it appears that Chokyi Dronma’s elevated status as royalty enabled her to receive ordination as a bhikshuni, important proof that the full bhikshuni ordination was available historically to at least some Tibetan women. Though a fully ordained nun, Chokyi Dronma wore her hair loose in the manner of a yogini, and Diemberger conjectures that she likely served as the consort of three tantric masters: Bodong Chogle Namgyal, her main teacher; Thangtong Gyalpo, the terton (treasure revealer) famous for his construction of iron bridges; and Vanaratna, one of the last Indian panditas who traveled to Tibet.

To her credit, Diemberger goes beyond gender considerations to discuss Chokyi Dronma’s contributions to the artistic and technological developments of her day. With exceptional determination and organizational capacity, Chokyi Dronma orchestrated the printing of Bodong Chogle Namgyal’s collected works, thereby contributing to seminal developments in printing technology; she inaugurated a water project to increase agricultural productivity in the region, though in the end the people failed to carry her plans to fruition; and she presided over building projects, including a nunnery, stupa, and, toward the end of her life, an iron bridge under the auspices of Thangtong Gyalpo. Chokyi Dronma also specifically promoted the cause of women, supervising the training of a substantial group of nuns and even composing a sacred dance for them at the urging of her teacher.

In highlighting Chokyi Dronma’s achievements, Diemberger downplays the degree to which, in her biography, this princess-turned-nun is represented as carrying forward the work of her two principal teachers, Bodong Chogle Namgyal and Thangtong Gyalpo. This lacuna is due in part to a feminist impulse to recover the achievements of a historical woman in order to counteract, as Diemberger aptly demonstrates, the tendency for women to disappear from the historical record over time. It remains an open question the degree to which Chokyi Dronma’s activities were principally directed in support of her teachers and to what extent she had her own agenda.

The strength of this book lies in Diemberger’s ability to draw the reader into the world of Tibetan politics and patronage, whereby the fortunes of a Buddhist lineage are inextricably tied to the political alliances of its supporter. Diemberger shows the remarkable way that the Dorje Phagmo line managed to navigate historical exigencies to maintain support through major political upheavals, including the establishment of rule by the Dalai Lamas in the seventeenth century and the recent invasion and occupation by the Communist government of China.

The crowning feat of this comprehensive work is a landmark interview with the Twelfth Dorje Phagmo’s sister, quoted at length in the final chapter. In this firsthand account, the reader learns how the two sisters fled Tibet in their youth on the heels of the Dalai Lama in 1959 and decided to return only months later at the urging of their parents. Upon return, the Twelfth Dorje Phagmo and her sister were greeted with “a special welcome as patriotic heroines” and feted at a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in Beijing, where she was called a female buddha by Mao himself. The political prestige of the Twelfth Dorje Phagmo has enabled Samding Monastery to be rebuilt, but the same cannot be said for its nearby nunnery, and Diemberger notes that few pre-1959 Bodongpa nunneries survive today.

Ten years in the making, When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty exhibits that rare combination of meticulous historical research and lively prose in recounting a tale that is sure to intrigue readers interested in Tibetan culture and Buddhist women alike. Only the passing of time will reveal the next chapter in the legacy of the Tibetan princess-turned-nun and incarnation of the tantric deity, Dorje Phagmo.