Boy, who is mere days away from his fifth birthday, begins to throw a tantrum in the library—something to do with both wanting and not wanting to watch a puppet show. The tantrum is really a gale-force storm that takes him over, and I drop to my knees in the center of the room and clutch his whole body tightly, so that neither of us will be injured. Nearly five years old. I thought we were beyond this, I think, and then, “akachangaeri,” the Japanese word for returning to the baby state, the state of innocence. All around us, there are books filled with words that convey stories, and the people walking by interpret (in different ways) this image: a mother clutching a screaming boy so completely that they are a live knot of shuddering, violent emotion.

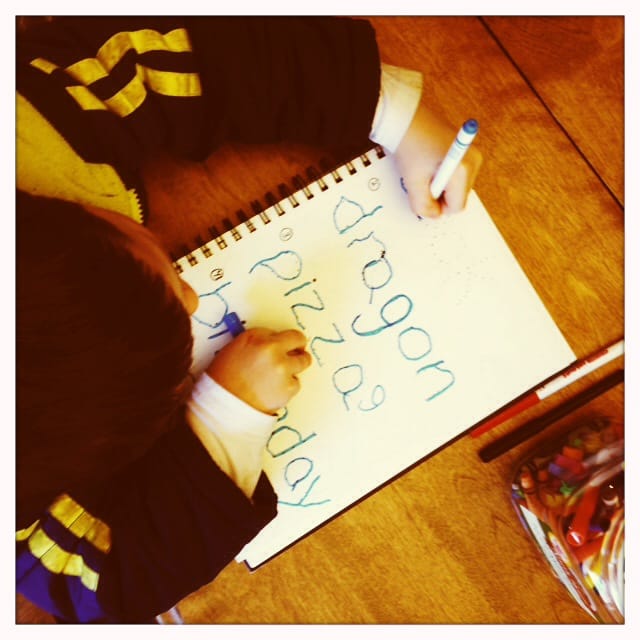

An hour later, at home, my son discovers a new love of writing, and I am floored for the second time this day. “Teach me words, Mama.” And so we make a game of it, him tracing (with his left hand) the characters I stipple into his sketchpad: b-o-o-k, d-r-a-g-o-n, a-p-p-l-e, b-i-r-t-h-d-a-y. I choose randomly, with no curriculum in mind. If I had been Japanese, if I had been writing in nihongo, I probably would have written verbs.

Then before bed, Boy asks, “What is your job, Mama?” And I explain (again) that it’s something to do with language, but that mostly others teach me. “ABCs, Mama?” And when I nod, he tells me that he has decided to become an artist when he grows up. “I will draw a picture of our family, and I will give it to you because I love you.” I am grateful for this because of the rawness I still feel from that moment in the library—I have been going over and over it all day.

For some reason that night, for the fifth or sixth night in a row, I dream about moving in a classroom between students (mothers and fathers from an inconceivable country), about trying again and again to convince them that the red apple in my hand is represented by the sketch of an apple on the handouts on their desks, and also by the letters on the blackboard that I am asking them to write: a-p-p-l-e. In this way, we struggle with signifier and signified, the idea that an image or some letters could point to a myriad of concepts. Red skin and spongy white flesh and sweetness and juice against the tongue can also be original sin, a single fruit bringing both knowledge and a loss of innocence simultaneously. A d-r-a-g-o-n can be a hoarder of gold or a winged embodiment of realization.

And the promise of a boy’s drawing of his family is really a story that can be read in many different ways.

This article originally appear at One Continuous Mistake.