I remember being embarrassed doing puzzles with my in-laws for the first time. While it took me quite a while to find a piece, they were fast because they were experienced puzzlers. After discovering the satisfaction of working on a thousand-piece puzzle, I noticed similarities with meditation and dharma practice.

With a puzzle, a person sits at the table with a thousand pieces scattered in all directions. They may say, “I don’t see any connections. How can I find anything?” After a few minutes they may say, “I can’t do this. This is not for me.” So, they give up. It may be true that the activity doesn’t work for them, but by giving up without putting in a good effort, they’ve lost the opportunity for their attention to grow.

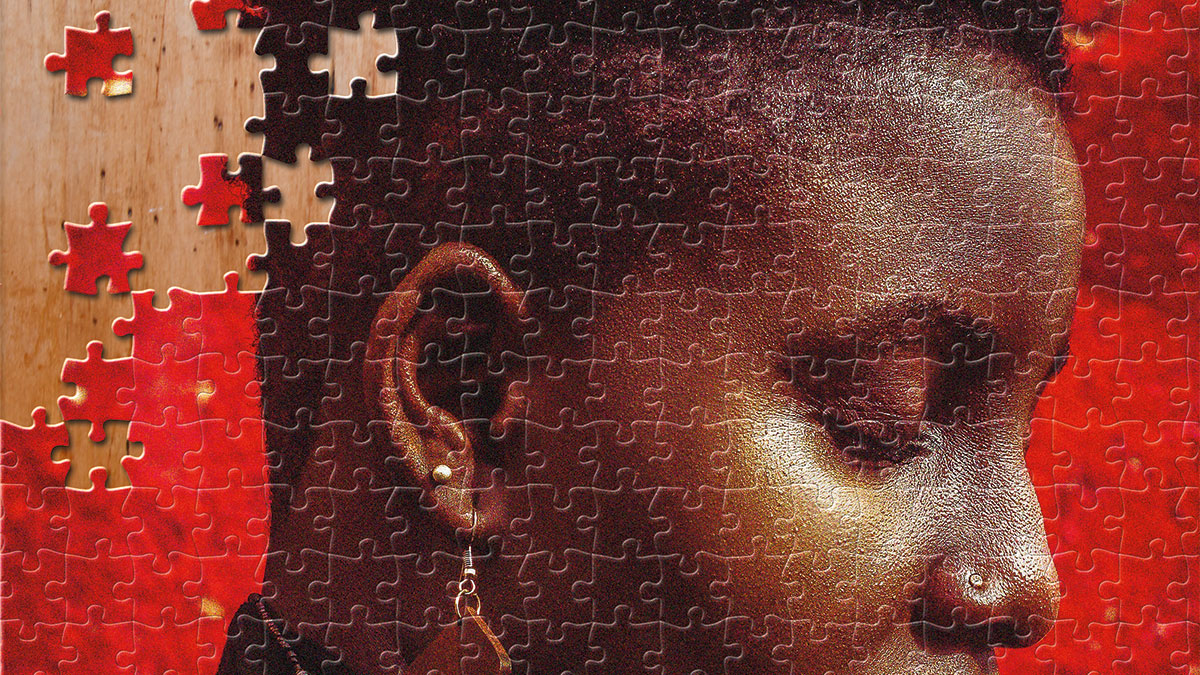

“When we learn to see thoughts come and go, we develop the attitude of the observer.”

For many, meditation is similar. They say, “How can I meditate with these thousand thoughts swirling in my head?” They don’t see the connection between following their breath and cultivating well-being. Nothing seems to make sense, so they think, “This is not for me,” and they give up quickly. Their attention does not have the chance to stabilize, nor does tranquility have the chance to arise.

Doing puzzles is a humbling experience, since we see how dispersed our minds can be. Our field of vision is bombarded with puzzle pieces, but when we try to focus on one piece, another attracts our attention. We then let go of that distraction and return to finding our initial piece. As we return, another thought pops up and takes our attention away. We believe we saw the piece before; we just don’t remember where. We can even swear that a piece is lost, simply because we cannot find it. That’s how unfocused our minds can be.

The good news is that as long as we keep returning to the task of finding the puzzle piece, eventually we will “see” it. This is what makes attention grow: a gentle but consistent persistence. It is like dripping water filling a bucket drop by drop. In my community in Brazil, we have a similar saying: It is grain by grain that the hen fills her gullet.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu says that mindfulness “is the ability to keep something in mind and remember to keep it in mind.” He also reminds us that the Buddha taught right mindfulness and not simply mindfulness. With right mindfulness, together with other aspects of the path, we keep in mind and remember to keep in mind what is beneficial and abandon what is not.

The simple task of finding a puzzle piece cultivates mindfulness and concentration, which spills over into our meditation practice. Moments of concentration in meditation then lead to additional moments of mindfulness in daily life. It is a snowball effect. This fundamental aspect of the Buddha’s teachings helps us understand cause and effect and can be applied to any part of our lives. We do this, that arises. We stop doing this, that ceases.

If there is a messy pile in front of us, it will take longer to see connections. So, separate the puzzle pieces by color or shape. In meditation, we see connections as we return over and over to the object of our attention. That process of returning is what gives the mind a chance to calm down, rest in the present moment, and watch our thoughts. In time, we realize how we create stress for ourselves by the frenetic way we think.

Sometimes we focus on small details in the puzzle. Other times, we look at the whole picture. In observing the breath in one spot, we narrow our attention. Other times we make our awareness broad. In the Anapanasati Sutta, for example, the Buddha encourages us to make our awareness include our whole body.

At one moment, the puzzle seems easy. Another moment, we want to quit. Similarly, we may be hitting a plateau in our meditation practice or encountering a seemingly insurmountable challenge. In moments like these, patience, creativity, persistence, and a gentle touch can help.

In the essay “A Decent Education,” American Buddhist monk Thanissaro Bhikkhu says, “when things like pain and distraction come up in the meditation…don’t get discouraged by how big the task is. Just keep chipping away, chipping away….when you come to meditation you need to develop the basic skills needed to deal with a long-term project: Keep chipping away, chipping away, step by step.”

We can train ourselves to improve our attention. A puzzle is one of endless activities that can increase our attention by bringing our minds to the present moment. At first it is all a blur, but with time it starts to make sense. Finishing a puzzle can bring a sense of accomplishment. We have cultivated attention and can now notice what we didn’t before.

As we meditate, we see our thoughts more clearly and question their reality. Insight meditation teacher Tara Brach says, “Thoughts are real but not true.” What this means is that their effect on the body is real, but we are often making them up.

When we learn to see thoughts come and go, we develop the attitude of the observer. This is an important step because observing our thoughts is a major goal of meditation. Otherwise, unskillful thoughts spill out in our words and actions when we are irritated.

Sometimes, simply acknowledging a thought’s presence is enough for it to go away. At other times, we need an active approach, especially with persistent and negative thoughts. Deal with those like a call from a strange number or a scam text—see it but don’t answer it, or glance at it and delete it.

We learn to notice that thoughts of understanding, forgiveness, generosity, compassion, and goodwill for ourselves and others have a positive impact on our emotions. How we think affects how we feel. This is the principle of cause and effect. Test it to see if it is true for you.

With more moments of mindfulness, continue observing your thoughts. Engage with thoughts when needed, or just step back and watch. By stepping back from our thoughts, we create moments of rest despite the conditions of our lives and this unjust world. Most importantly, we create positive causes for this moment and the next. The practice is to pay attention to one breath at a time, one moment of mindfulness at a time, and one thought at a time. Even when there are a thousand thoughts.