White Lama: The Life of Tantric Yogi Theos Bernard, Tibet’s Lost Emissary to the New World

By Douglas Veenhof

Harmony Books, 2011

$27.50; 446 pages

The life and writings of Theos Casimir Bernard, the first American Buddhist pilgrim to reach Lhasa, inspired many Westerners to learn more about Tibet and its religion. He was also an influential popularizer of hatha yoga but has been virtually forgotten since the 1960s. These biographies, however, should revive interest in this single-minded visionary.

In the 1930s, when Bernard began his public career, yoga was still an exotic practice in America. There were few teachers, and some were little more than charlatans, like his uncle Pierre Bernard, known as “The Great Oom.” There were no Tibetan Buddhist teachers in the United States, and Tibet itself was conflated with the mythical Shangri-la of James Hilton’s wildly popular 1933 novel, Lost Horizon, and the movie based on it. The eventful life of Theos Bernard, an ambiguous personality—“part mystic, part explorer, and part con man,” as Robert Thurman put it—contributed to the movement of Asian teachings and practices from the counterculture fringe to the American mainstream.

Born in 1908 to parents immersed in Eastern spirituality, much was expected of the son they named Theos, Greek for “god.” When he was a baby, his father, Glen, abandoned the family to pursue yoga studies in India, and Bernard grew up with his mother and stepfather in Tombstone, Arizona, where the rugged desert hills prepared him for his Himalayan treks. The handsome and athletic Bernard was a hero to other boys and a charmer to many girls. He glided through college in Tucson with a C average, later got a law degree, a master’s in anthropology and a doctorate in religious philosophy (the last two from Columbia University). He reunited with his father in Los Angeles in 1931 and Glen, who had studied with Indian teachers and read the available English literature on Hindu tantra, became his son’s yoga guru.

In 1933, unemployed in the midst of the Great Depression, Bernard read an article about Uncle Pierre’s ashram– resort in Nyack, New York, which is described at length in Veenhof’s book. Upon learning that it was attracting famous and wealthy followers, Bernard hurried east with dreams of becoming his uncle’s successor. The attractive yogi made a favorable impression (his aunt “swooned” on first seeing him) and he became involved with Viola Wertheim, a young heiress. They married and embarked on a luxury honeymoon tour of India. Bernard stayed behind when she returned to America, supported by $500 a month from his wife, a vast sum in India in those times. Hackett’s book is especially detailed about the financial underpinnings of Bernard’s enterprises, facts that Bernard himself never alludes to in his memoirs.

After a series of unsatisfying encounters with Indian yogis and scholars, Bernard went to the eastern Himalayan hill station of Kalimpong, the seat of the Tibetan community in India, because he had heard that the real secrets of tantra could be found only among the Tibetans. In Kalimpong he met men who were to prove pivotal in his life: Gergen Tharchin, an important figure in Tibetan cultural life and publisher of the first and, at that time, only Tibetan newspaper; Geshe Wangyal, a Kalmyk Mongol graduate of Drepung monastic university in Lhasa; and former monk Gendun Chopel, perhaps the foremost Tibetan intellectual of the past century.

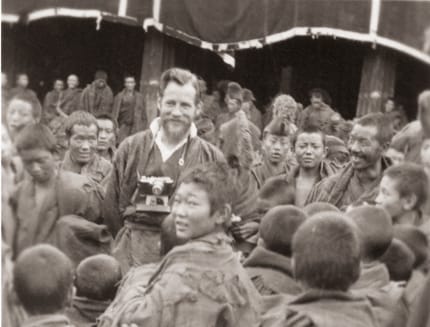

Bernard began his study of Tibetan with Tharchin and Geshe Wangyal; according to Hackett, Bernard became quite proficient in the colloquial language, but he never fully mastered literary Tibetan. At the same time, he engaged in brilliant networking with Tibetan aristocrats and British officials that enabled him to get a seldom-granted permit to visit Gyantse (the main British entrepôt in Tibet). There, he secured an even rarer privilege—a passport to Lhasa, the Tibetan capital. In June 1937 Bernard arrived in Lhasa, the second Western Buddhist pilgrim to do so (not the first, as both books have it; that distinction went to the indomitable French Buddhist, Alexandra David-Neel, who reached Lhasa in 1924). During his intensely busy three-month stay, Bernard (accompanied by his interpreter and invaluable aide, Tharchin) made an extensive film and photo record and amassed a vast and choice collection of Tibetan Buddhist texts and ritual art. Both Veenhof and Hackett discuss the fate of these significant collections; for the most part they remain uncataloged and inaccessible to the public and even scholars.

As soon as he returned to India, Bernard began the work of promoting his plans for a Tibetan Buddhist institute and other projects, including the impossible task of rapidly translating the entire Tibetan Buddhist canon, with the aid of one or two Tibetans. He told reporters he was “the first White Lama—the first Westerner ever to live as a priest in a Tibetan monastery, the first man from the outside world to be initiated into Buddhists’ mysteries hidden even from many natives themselves.” These statements, which formed the basis for his highly fictionalized memoir, Penthouse of the Gods, and his lecture tours, were wholly untrue, as Hackett clearly shows. Bernard never lived in a monastery, received no esoteric secrets unavailable to others, and would not have been regarded by any Tibetan as a lama. What Bernard had done in Lhasa was use his wealth to sponsor teachings, for which he received initiations, including tantric ones (commonplace today). He may have thought that these exaggerated tales (and his often repeated claim to be the incarnation of Padmasambhava, the legendary yogi saint who helped establish Buddhism in Tibet) were necessary to gain support for his work from a public that craved the marvelous. Alternatively, given his grandiose personality, he may have come to believe his own fabrications.

Returning to the States, Bernard and Wertheim had a disappointing reunion; she found him to be erratic and possibly mentally disturbed, and divorced him, granting a large financial settlement. Bernard then embarked on successful lecture tours (appearing in Tibetan monastic robes), wrote books about his travels, yoga, tantra, and Tibetan grammar, got his Ph.D. (based on his hatha yoga experiences), and eventually opened a yoga studio in New York City catering to wealthy, mostly female, students. After one of them suffered a mental breakdown and was hospitalized, her husband sued him, and the court case and its scandal left him in relative poverty.

He then declared his love for one of his former students, Madame Ganna Walska, whose five divorces had made her very rich. Walska, a histrionic wouldbe opera singer who lacked talent, fell passionately in love with the charismatic and much younger Bernard. He persuaded her to secretly marry him and to buy two large estates in California near Santa Barbara, one (“Tibetland”) to be the site of his translation institute, and the other (“Penthouse of the Gods”) for his private meditation retreat. He strenuously attempted to get Gendun Chopel a visa to head the institute, but it was 1940 and war in Asia rendered the plan impossible. Bernard spent little time with Walska, who eventually found out about his involvement with other women and divorced him.

In 1947, Bernard returned to India with his new partner, Helen Park, settling again in Kalimpong and studying with Geshe Wangyal, who pointed out Bernard’s ignorance about the basics of Buddhism. Bernard then began studying Buddhism and literary Tibetan in earnest, but he tragically did not follow his teacher’s advice to cancel a planned trip with Park to Kashmir. This was immediately before the partition of India and Pakistan, and widespread violence had already erupted across the north. Bernard was murdered while returning from a visit to a monastery in Spiti, either by anti-Muslim thugs or bandits. Veenhof opts for the former story, while Hackett, based on his fieldwork in India, states that robbery was the motive and that the killers were known.

As both these books indicate, Bernard’s influence lay more in his example and ambitions than in what he managed to accomplish during his thirty-nine years. His yoga writings continue to be read, and Penthouse of the Gods pointed the way to India and the Himalayas for many later American pilgrims, including Allen Ginsberg and Philip Glass.

Bernard did have a prophetic gift; he clearly saw the imminent doom of traditional Tibet, and his plans to bring Tibetan teachers to America to translate texts and promulgate Tibetan Buddhism have been fulfilled by others who followed him. Geshe Wangyal, whom he had intended to bring to America, did arrive in 1955 and was a major force in the development of Tibetan Buddhist studies. To use a familiar Buddhist metaphor, Bernard planted the karmic seeds for Tibetan dharma to grow and flourish on American soil.

The two biographies cover much the same ground, although in different ways. Veenhof’s account is a breezy journalistic read that’s ideal for the general reader. Hackett had a different objective: not only to recount Bernard’s life and milieu but to trace the naturalization of yoga and Tibetan Buddhism in American culture. His writing is fluid and at times witty, and the density of the book’s detail calls for a close reading. Bernard met many figures of greater importance than himself, and Hackett rightly devotes long passages to Gergen Tharchin, Geshe Wangyal, Dasang Damdrul Tsarong (Bernard’s host in Lhasa, a heroic general and leader of the failed movement to modernize Tibet), Gendun Chopel, and Reting Rinpoche (regentruler of Tibet during this period).

Hackett’s expertise in Tibetan language and culture and his fieldwork in India have greatly enriched his narrative. Despite his occasional over-idealizations of Tibetan history and culture, he has written a lively and significant study that deserves the attention of anyone interested in the history of Asian religion in America.