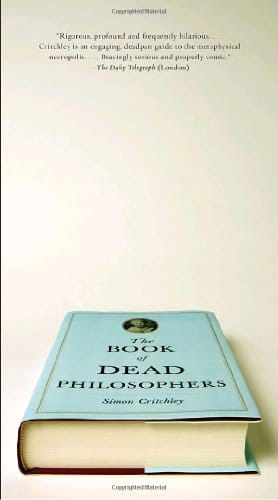

Andrea Miller interviews Simon Critchley, philosophy professor at the New School for Social Research in New York and author of The Book of Dead Philosophers.

Maybe your Philosophy-101 textbook was dry as a bone and your philosophy class (MWF 11 a.m.–12 p.m.) was a good opportunity to doze. But don’t hold that against Simon Critchley. Though he’s professor and chair of philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York, he’s not like the prof you had. His latest book, The Book of Dead Philosophers, unpacks three thousand years of philosophical history by explaining how “190 or so” philosophers have kicked off. And this, surprisingly, is a lively read—life affirming and morbidly funny.

Why a book on dead philosophers?

Philosophy began with a death. Socrates walked around Athens asking questions no one had ever asked before. Difficult, universal questions about the nature of things: What is justice? Beauty? Truth? People answered Socrates’ questions and he picked apart their answers, but he didn’t provide answers himself, just a series of perplexities. For that he was executed by the authorities. The philosopher always has his or her eyes on death. Focused on questions of finitude, he’s already in a sense half dead himself. To philosophize is to learn how to die in the right way, at the right time. This is what the philosophical tradition keeps coming back to.

Is there such thing as a good death?

I think so. Dignity is key. Most people now die in a drug-induced state, and in some cases this interferes with dignity. In the past, a lot of people died in pain, but that wasn’t necessarily bad. A great example is Epicurus. He died in enormous pain, yet he endured and died with tranquility. This was essential to his teaching: do not fear death.

These days, the overwhelming issue is not dying in pain, not being a burden to anybody else. So there’s a sense that you should drug people, pacify them. Yet there are people in the modern age who have done other things—Freud, for instance. He had twenty-seven operations for cancer of the mouth and refused to take painkillers because, he said, he’d rather think in pain than not think at all.

How else has the culture of death changed over time?

In the past, deaths were often group acts—the dying were surrounded by friends. And death was something that was meditated on throughout life. It wasn’t something one tried to run away from. Our culture denies death in a dramatic way, particularly in the U.S., where most people have never even seen a corpse. Looking at the history of the philosophical death can get people to look at the skull beneath the skin—to focus on the one certainty in life, apart from taxes, which is that life ends.

Has any other society denied death to the extent we do?

Societies have denied death in different ways, but we’re so extreme it’s difficult to think of a precedent. We shuffle dying off as something that happens to other people, not to us. We see death as obscene. The Victorians had difficulties with sex but they had a powerful death culture and were very good at commemorating it. We’re the opposite. We can talk about sex until we’re blue in the face but we cannot face death. We’re terrified of it. This is strange in an overwhelmingly Christian culture, because Christianity is a meditation on death. It’s about learning to die in a certain way. Longevity wasn’t something of much value in early Christianity—a brief life was often a more worthy life. The denial of death is the overwhelming desire for longevity at all costs, and the gods people believe in are the gods of medical technology. I’m not against that but we should be thinking about the issue more carefully.

What about the classical Chinese philosophy of death?

Confucianism was all about the right manners and the right behavior, so the Confucians were obsessed with rituals around death. Daoists rejected that, thinking death was a passage from one state to another: We’re human beings, we become worm food, and then we might become something else. Who knows? The Daoist Chuang Tzu laughed and banged on a tub after his wife died, saying, “My wife has left me.” Then a friend said, “How can you possibly laugh when your wife is dead?” “We lived together,” Chuang Tzu said, “We had children. We had a wonderful time. Now she has transformed. Why should I be sad?” The Confucians were appalled by this because it seemed to show no respect for the dead.

Tell me about Japanese death poems.

On the verge of death, Zen monks write a haiku or short elegiac poem. They pronounce it, and then set aside their ink brush, cross their arms, straighten their back, and die—often in the meditative position. It’s pretty impressive [laughs]. An example of one of these poems is “the joy of dew drop in the grass as they turn back to vapor.” There’s a wonderful story of a Zen Buddhist monk from the twelfth century who preached to his disciples and then sat in the Zen position and died. When his followers complained he died too quickly, he revived and harangued them for a bit longer. Then he died five days later. This was about controlling the moment of his death.

Which philosopher’s death appeals to you most?

I like Wittgenstein’s. He was diagnosed with cancer a month or two before he died and he treated the news with great relief. He then moved in with his doctor and struck up a firm friendship with his doctor’s wife, Mrs. Bevan—going to the pub with her every night. He died the day after his birthday, but on his birthday Mrs. Bevan gave him an electric blanket and she said, “Many happy returns.” Then Wittgenstein said, “There will be no return.” There’s something sober and funny about that, which I think is important. It’s important to maintain a certain lightness toward death. To face up to it and replace the terror with sober humor.

You wrote another book called On Humor. What’s the connection for you between philosophy and comedy?

Philosophy asks you to look at the world as if you were from another planet and to question everything—the nature of reality, the external world, other people. That’s like comedy—great comedy, not the dreary stand-up routines you usually see. At their best, both comedians and philosophers shake out your prejudices. Jokes can liberate and elevate us and even change the situation we find ourselves in.

We fear our own deaths, but there’s also the problem of dealing with the deaths of loved ones. How do philosophers help us work with that?

Badly. The question of death was really posed for me through the death of my father and friends. But the philosopher’s death is about my death and me dying calmly, with dignity. This doesn’t get at the difficulty of our response to the death of those we love. That’s why in The Book of Dead Philosophers I spend the time on early Christian philosophers—they had the best sense of grief. Now I’m working on a book about the nature of love, particularly the nature of mystical love. Philosophy has a lot of wisdom about what the world means, and that’s fantastic, but it doesn’t have a rich enough vocabulary for the question of love.