When she was a child growing up, Mayumi Oda loved visiting an ancient shrine in Kamakura. Located in a cave, it was dedicated to the Hindu/Buddhist goddess Sarasvati, known in Japan as Benzaiten. Because Benzaiten is a goddess of wealth, people would wash their wallets and purses in the spring running through the cave, and they’d leave offerings of eggs for the white snakes associated with her.

One day, the young Oda encountered a guardian of the shrine, a seer. With one skillful stroke he was painting a serpent, vibrating the brush to create scales. “Young girl,” he said, “you are going to be a successful painter.”

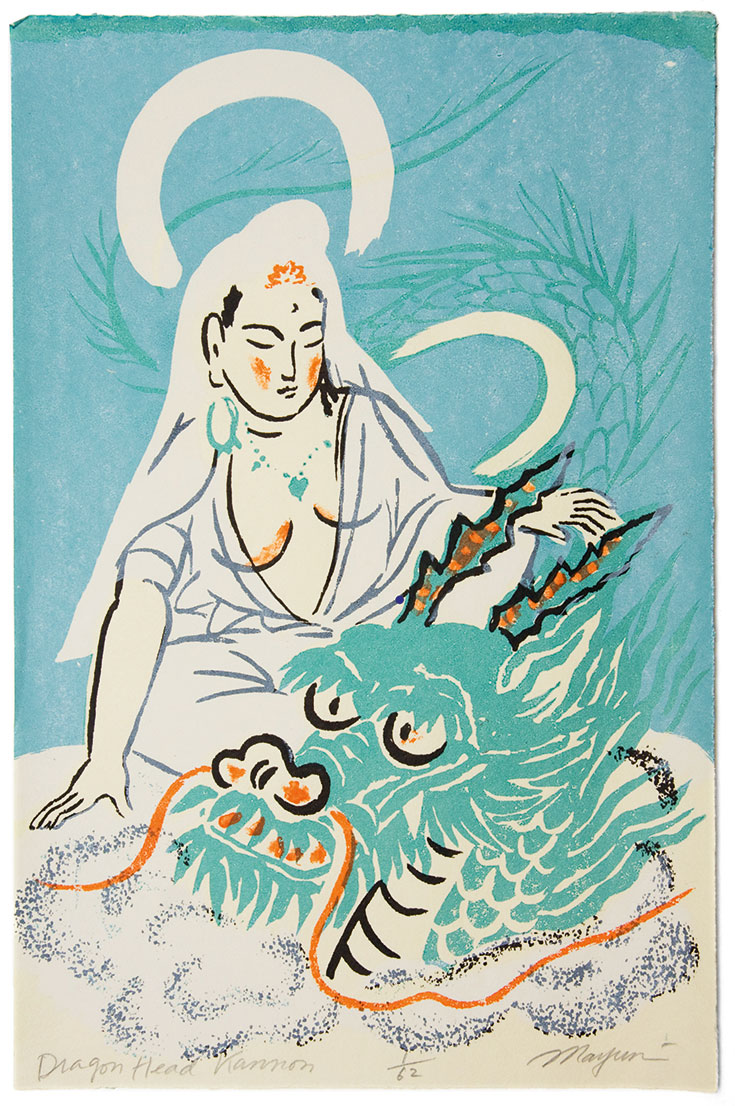

Mayumi Oda, now aged seventy-nine, is known as the Matisse of Japan. Her signature style is an elegant, heartfelt whimsy that’s infused with spirituality, sensuality, and vivid color. She’s had more than fifty solo shows internationally and her work is in such high-profile permanent collections as those of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the U.S. Library of Congress. But in addition to her prodigious creative output, Oda has had a rich life as a Buddhist and activist, mother and farmer.

“It’s not that I became a Buddhist,” she tells me. “I was born a Buddhist. It’s in my blood.”

As a child in Japan, Oda chanted mantras every morning and evening with her family, sitting together in front of the altar in their home. They were adherents of Nichiren, a Mahayana school of Buddhism centered on the Lotus Sutra, although Oda’s father had practiced Zen as a student at Kyoto University. He taught her the importance of respecting oneself, not harming others, and concentrating on the moment. He frequently quoted the Buddha: “On heaven and earth, we are the world-honored ones.”

Whatever comes is coming from a bigger place than me.

But Oda felt stifled by the gender expectations of everyone around her. Envious of boys with their freedom, she tried to pee standing up, while on another occasion she climbed onto a rooftop, pretending she was Tarzan. You’re a girl, she was scolded and punished. Act like a girl. Finally, in high school, Oda read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, and felt the book gave voice to her experience.

In 1962, Oda was accepted into the crafts department of the Tokyo University of Fine Arts, and in her freshman year she met John Nathan, an American who’d later become a celebrated translator and Emmy-award-winning documentary filmmaker. On a rainy afternoon in a Tokyo garden, he walked over to Oda and said in fluent Japanese, “Here we are in love, under the umbrella together.”

Soon, Oda and Nathan were whiling away the hours in jazz coffee shops, having juicy conversations about Japanese culture, art, and literature. Nathan, Oda felt, was the first person to truly understand her. As she explains in her upcoming memoir, Sarasavati’s Gift, “I felt so free with him, and he didn’t see anything wrong with my freedom.”

After they’d been dating for two months, Nathan proposed. Hearing this, Oda’s mother cried. “I like John. It’s just that foreigners…” she paused, “make my skin crawl.” Oda’s father said the decision was hers.

Oda and Nathan honeymooned in the Fukushima region, enjoying the green mountains and autumn leaves. Then Nathan and Oda moved in with her family in the suburbs of Tokyo, and the couple continued their studies.

Oda’s degree was in fabric design and dying. She’d chosen it because she admired the sumptuous kosode robes and Noh costumes of the Momoyama and Edo periods. But, as she puts it, the rest of the curriculum—“copying lifeless old scrolls and stilted Buddhist flower patterns”—left her cold. Oda would skip class to go to the Tokyo National Museum, where she’d lose herself in the folding screens, pottery, and lacquerware. This, she’d realize later, gave her a solid education in the essence of classical Japanese art.

In 1966, Oda and Nathan spent two months traveling across Siberia and Europe, eventually landing in New York, which became their new home. A whirlwind of wild parties ensued, and the couple brushed shoulders with prominent musicians, writers, and artists such as Andy Warhol and Mark Rothko.

Meanwhile, the antiwar movement was sweeping over America, and along with tens of thousands of others, Oda marched from Central Park to the United Nations, singing “We Shall Overcome.”

In 1967, she gave birth to a baby boy. Oda herself had been born into war and, at age three, she’d survived the American firebombing of Tokyo on March 9, 1945. This firestorm incinerated more than 200,000 people, making it the single most destructive bombing raid in history. Oda had huddled in a bomb shelter beneath her family’s lotus pond, and now she feared for Zachary, her newborn son. With the Vietnam War raging, she wondered if, when he grew up, he’d have to be a soldier.

Despite her worry, childbirth allowed Oda to tap into a primal strength. She began attending women’s liberation meetings and creating images of voluptuous women reminiscent of Neolithic fertility goddesses. Then in 1970, Oda gave birth to her second child, Jeremiah.

The young family moved to Princeton, New Jersey, where they lived in an eighteenth-century farmhouse, nestled in a soybean field. In the attic, Oda built a print studio, where it seemed as if images flowed through her.

In her large, colorful silk screen prints, she had her own fresh take on Edo-period ukiyo-e. She was dreaming up scenes of women—goddesses—who were at one with nature. They were, as she describes it in Sarasvati’s Gift, “diving into the ocean, frolicking through flower gardens, soaring in the sky.” Oda began receiving invitations from galleries and museums to show her work; she became a professional artist.

Oda reluctantly agreed to return to Japan while Nathan was making a trilogy of documentaries called The Japanese. As she saw it, Japan had changed—had become more corporate—and America had changed her. She felt she no longer belonged in either country.

One night, Oda had a nightmare. She was an oversized tatami mat in a tearoom, and her mother was stomping on her, trying to force her into a space that was clearly too small. Oda woke up screaming, “It hurts!”

Miserable in Japan, she sought balance at a Soto Zen temple in Tokyo, where she could practice zazen. But she found the temple oppressively patriarchal—women were even forbidden from entering the zendo.

It wasn’t long, though, before Oda met a group of Zen practitioners she truly connected with. Some American Buddhists, including Richard Baker Roshi, then abbot of San Francisco Zen Center, were in Japan to attend a ceremony. They invited Oda to summer at their farm in California, Green Gulch Farm Zen Center, and so she did, bringing along her two sons. “I fell in love with the practice, the garden, and the community,” Oda has said.

She and Nathan acknowledged that they’d been growing apart, and soon they separated. Oda moved into a house with other Green Gulch mothers and children, and they looked out for each other. They shared some meals and childcare duties, and helped one another follow the meditation schedule. Oda steadily painted and worked in the garden.

Years went by, and her career blossomed. Among other accomplishments, she published Goddesses, a book of her silk screen prints, which captured the hearts of those longing for empowered female imagery, and she created massive goddess banners to bless a conference at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. But then, as Oda puts it, she “heard the call of Sarasvati” and turned her attention from art to activism.

In 1992, Oda learned from a friend about a plan the Japanese government was trying to keep under wraps. Over a ten-year period, Japan was to receive thirty tons of plutonium from France—enough to make 150 nuclear bombs—to fuel fast breeder reactors. Japan had already built more than forty nuclear reactors and intended to build more.

Oda was baffled, devastated, and furious. She was four when atomic bombs were detonated over Nagasaki and Hiroshima and could vividly remember seeing burned survivors begging for alms. Why would a nation that had suffered in this way embrace nuclear energy, especially when earthquakes and tsunamis made nuclear power plants absurdly dangerous?

One morning, Oda was meditating in front of her Sarasvati statue when, she believes, the goddess spoke to her: “Stop the plutonium shipment.”

Oda’s sons were grown and she’d amassed some savings from selling her prints, so she felt this was the right time to dedicate herself to making the world a better place. All the same, Oda wondered how she could do what was being asked of her.

“Help will be provided,” Sarasvati answered.

Oda’s first step was to reach out to peace activists in the Bay Area and form a group called Plutonium Free Future. Then, she and several others, including calligrapher and Zen teacher Kazuaki Tanahashi, established Inochi, a foundation dedicated to stopping the plutonium shipment and—ultimately—protecting all life. As they worked to organize conferences, meet with officials, produce publications, and raise funds, Oda felt divinely supported.

A golden opportunity arose when Oda received an invitation to exhibit her art at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Tokyo. There she got to address forty international journalists about Japan’s nuclear plans, and foreign correspondents’ reportage was not censored by the Japanese government. Just weeks after the luncheon, Newsweek Japan’s cover story was “Japan Loves Nuclear.”

Soon people from all corners of the globe were aware of the plutonium shipment that would sail to Japan via the Panama Canal. Oda felt uneasy about having revealed a government secret, but she went on to make an even bolder move—she and a team of others sued the Japanese government over the importation of plutonium.

Ultimately, Oda wasn’t able to prevent the shipment. When asked how she’s managed to move on from such a setback, she simply says, “I don’t think about it. You have to do something, you do it.” So Oda persevered.

At one point, Daniel Ellsberg, who’d leaked the Pentagon Papers and was himself affiliated with San Francisco Zen Center, invited her to a Japanese nuclear industry conference in Hiroshima. The industry was presenting nuclear energy as the solution to global warming, and the president of Mitsubishi was heralding plutonium as “pure gold.” Oda felt she needed to talk to these Japanese leaders in English in order to not be perceived by them as an irrelevant woman. When she asked them how much research they’d conducted on the dangers of nuclear reactors in an earthquake or tsunami, and how they were preparing for the storage of nuclear waste, they claimed to have everything under control. Sadly, Oda was not surprised when the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster proved them wrong.

There is no life; there is no death. There is only this moment of pure truth.

After nearly ten years of working tirelessly to bring change to the nuclear industry, she was exhausted and decided to step back. She would strive to repair society in other ways.

In 2000, Oda purchased Gingerhill Farm, a five-acre ranch in Hawaii. Her plan was to grow medicinal herbs while building a sustainable community. According to Oda, “The ethics of kindness, love, and compassion toward our gardens, our food, and one another permeate every aspect of our lives at Gingerhill Farm even to this day. … Young people from all over the world have come to Gingerhill Farm to work, grow fruits and vegetables, cook together, and take care of their bodies and minds.” In addition to apprenticeship programs, there are retreats and a B and B. Today, Oda’s son Zachery and his wife Iris are the directors of the farm.

Oda’s son Jeremiah, known as G, grew up to become a graffiti artist and graphic designer who specialized in designing colorful skateboards. He was also an accomplished swimmer, diver, and fisherman. As Oda puts it, “He was like Neptune.”

In 2013, G went missing in the turquoise waters of Honaunau Bay, and no trace of him was ever found. Shortly before his passing, he had the Heart Sutra in Sanskrit, interwoven with the design of a Hawaiian lei, tattooed across his chest. The famed conclusion of the sutra says, “Gone, gone, gone beyond, to the other shore, awakening fulfilled, oh great joy!”

Oda writes, “I realized the true meaning of this sutra: freedom from suffering. There is no life; there is no death. There is only this moment of pure truth, just a continuation of love and the spirit of oneness. This was a gift G gave me.”

These days, Oda practices every morning and evening with her family, just as she did when she was growing up. Her current practice is a little different, though. As a child, Oda always chanted Nichiren sutras. Now she chants those on weekends, while from Monday to Friday she chants Zen sutras.

Oda considers herself both a Zen and Nichiren practitioner, making no distinction between the two. In fact, as Oda sees it, all religions have the same essence, and this is why she finds it compelling to create female imagery not only from the Buddhist tradition but from all traditions, including Christian, Mesopotamian, and Native Hawaiian.

Oda paints goddesses because she believes a “feminization” of our society is necessary if we wish to survive our current political and ecological crisis. In the goddess figure we find reverence for the earth. We find compassion, innate wisdom, and creativity.

Preparing to paint, Oda meditates and traces sutras. “I calm down,” she says. “I clean my heart. Then I’m ready to get inspired, and whatever comes is coming from a bigger place than me.”