In my freshman year of college, my religious studies class was at the sleepy hour of two o’clock, and to make matters worse the professor was hypnotically soft-spoken and wore tired shades of brown. So on the day that he slowly enumerated the four noble truths on the board, I failed to experience the flash of insight, which many Buddhist converts talk about; the only thing I felt was my heavy eyelids.

Then I glimpsed movement.

I was sitting by the window—sunlight pouring in—and a dark, glossy bird I didn’t have a name for had landed on the stone windowsill outside. If it weren’t for the glass, I could have touched it—I was that close to its iridescent purple and green sheen, blunt tail, and yellow bill. Watching the bird tilting its head as it looked at me with alert, shiny eyes, I was suddenly wholly focused.

I’d never before paid much attention to birds, but for me this particular one was what Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh calls “a bell of mindfulness.” The bird woke me up to the present moment.

It was inevitable: I became both a Buddhist and a birdwatcher.

For me, birding is a form of meditation—it’s just watching, just listening. I appreciate how birding encourages equanimity, how it helps me rest in ambiguity and uncertainty. In the field, I get a glimpse of small, brown wings disappearing through the branches of an oak. Then I look through my bird books and see page after page of almost indistinguishable little brown birds with their subtle markings and minor differences. Did the bird I see have yellow or tan legs? Was its beak straight or did it curve? I can’t positively identify the bird and I have to find some peace with that.

It’s easy to find symbolism in birds—in the way they take flight, in the way they preen and nest and sing. Poets have long made wordy use of their wings, while mystics have revered them. In Buddhism, birds are used to teach ethics and concepts. They are metaphors for our muddled, unskillful selves, and also represent our best, no-self selves. Buddhist bird lore goes all the way back to the beginning, or so the story goes.

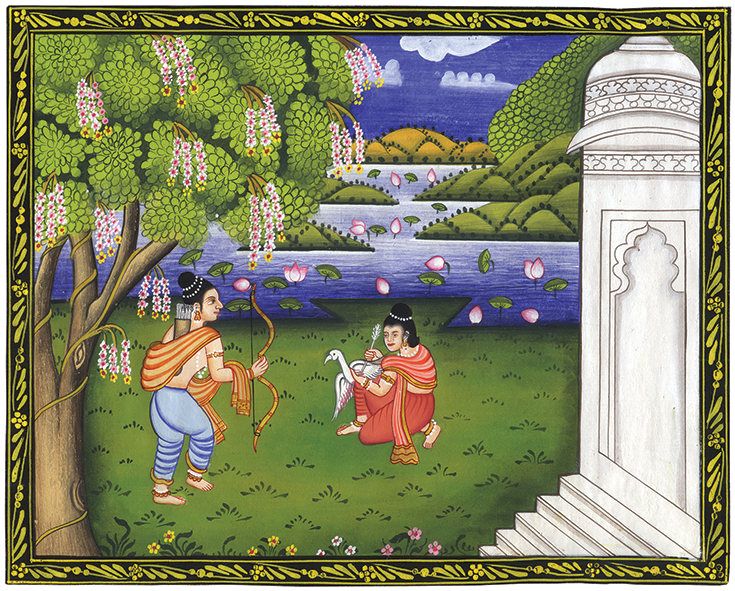

Siddhartha and the Swan

One day, when the future Buddha, Siddhartha, was just a child, he and his cousin Devadatta went walking in the forest. Devadatta was an avid hunter, never without his bow and a sheaf of arrows, so when a wedge of swans passed through the sky, he aimed at the leading bird and pierced its wing. As the swan fell heavily to the ground both boys ran to it, but it was Siddhartha who arrived first. He cradled the injured creature in his arms and whispered comfort into its curved, milky neck. Then he extracted the shaft of the arrow and rubbed the wound with a cool and soothing herb.

Eventually, Devadatta caught up to Siddhartha and demanded he hand over the swan, but Siddhartha refused. When Devadatta persisted, Siddhartha suggested that they bring the matter to the king, and so in front of the whole court Devadatta and Siddhartha each presented their side of the argument. They were both so persuasive that the court was divided; some people thought that the swan belonged to Devadatta because he shot it, while others believed that it was Siddhartha’s for nursing it.

Suddenly, an elderly man appeared and the king asked him his opinion. “The prized possession of every creature is its life,” the elder stated. “As such, a creature belongs to whoever protects it, not to the one who attempts to take its life away.”

Seeing the wisdom in this, the court awarded Siddhartha the swan. He sheltered it until it was fully healed, and then set it free.

The Golden Goose

The Buddha often told his followers stories about his previous lives to teach them ethical lessons. According to one story, he was a man who died and was reborn as a golden goose. He still remembered his old family and felt a pang thinking of how, since his death, they were just barely scraping by. So he went to them and at their feet he released one of his valuable feathers. “I’ll always provide for you,” the goose promised. Then each day after that he gave the family another feather until they had enough gold to buy soft beds and rich foods.

But his former wife grew greedy, and one day she lured the goose close to her with sweet words. Then she grabbed him, pinned his beating wings between her chest and the crook of her arm, and plucked all of his resplendent feathers. Now, the goose couldn’t fly away, so his wife threw him into a barrel, fed him skinny scraps of food, and waited for his feathers to grow back. But when they did, she was disappointed: instead of the golden glint she was hoping for, the new feathers were as white as icy silence.

The Rooster of Attachment

Buddhist teachings place a bird at the very center of the wheel of life, the bhavacakra. At root, Buddhism is about how we can find true liberation from the suffering of samsara, the wheel of cyclic existence. The bhavacakra, which some say the Buddha himself created as a teaching tool, is both a diagram to help us see why we’re stuck in samsara and a map to help us find freedom from it.

At the hub of the wheel of life there are three animals: a bird, a pig, and a snake. In English we refer to this bird as a rooster or cock, but Tibetan teacher Ringu Tulku says that it’s actually an Asian species, one that is obsessively attached to its mate. The bird, therefore, represents desire, clinging, or attachment, while the snake symbolizes aggression or aversion and the pig symbolizes ignorance or indifference. Together, these three animals represent the three poisons—passion, aggression, and ignorance—that drive the wheel of samsara.

The wheel of life is both a diagram to help us see why we’re stuck in samsara and a map to help us find freedom from it.

If you look around, you may notice that the whole well of our world is poisoned. From the spider crawling on your shin to the climate crisis to a box of chocolates with creamy centers—everything in our unenlightened lives always comes down to “I want it,” “I don’t want it,” or “I don’t care about it.” It’s through this attachment, aversion, or indifference that karma or action arises, which in turn gives rise to suffering. In short, the three poisons are the venomous fuel that drives samsara.

Look again at the animals in the center of the wheel. Frequently, the bird and snake are depicted coming out of the pig’s mouth, while at the same time they are clenching his tail. This hints at how the poisons bleed into each other: desire and aversion not only stem from ignorance, they also feed it.

As Roshi Bernie Glassman puts it, “The basic poison is ignorance, which means being totally in the dark, not seeing life as it is because of egocentric ideas.” But, he continues, “If we are rid of the self, the three poisons become transmuted into the three virtues of the bodhisattva. Ignorance becomes the state of total nondiscrimination, so we no longer discriminate between good and bad; instead we deal with what is in the appropriate way. Similarly, anger becomes determination and greed becomes the selfless, compassionate desire of the bodhisattva to help all beings realize the enlightened way.”

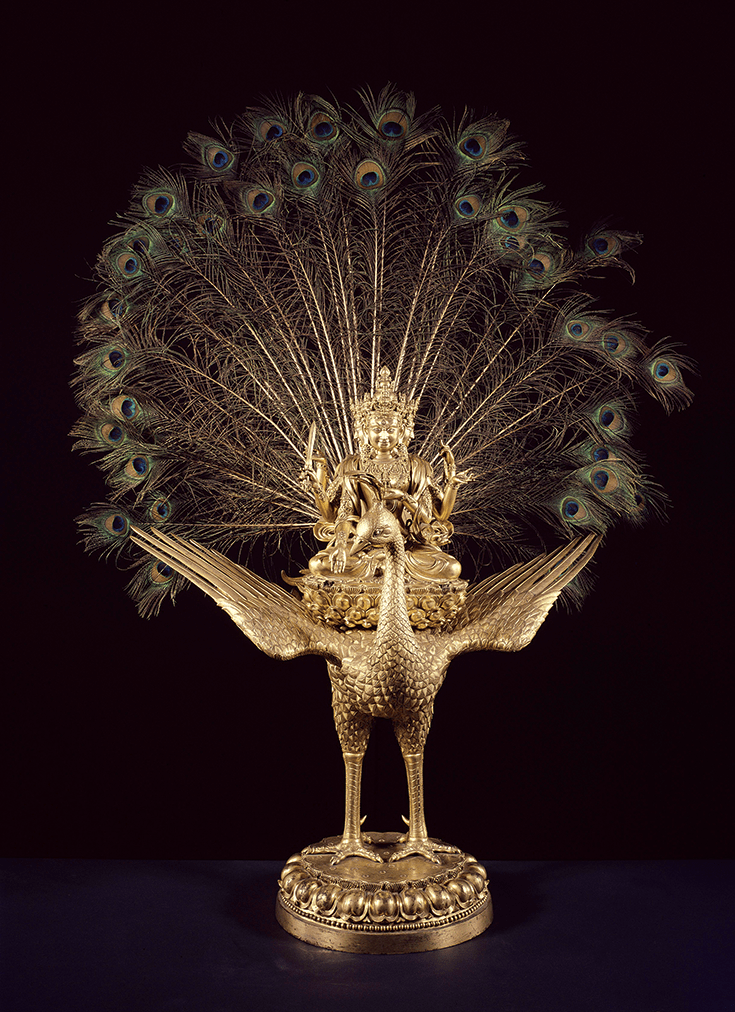

Peacock in the Poison Grove

When the monsoon started and the Buddha and his community of monks and nuns gathered for the annual rainy season retreat, they would often hear the plaintive call of the peacock. Ever since then, this bird with its electric blue throat and tail strewn with eyes has captured the Buddhist imagination.

Peacocks are credited with being able to eat poisonous plants, snakes, and insects, and not only survive but thrive. For this reason, these boldly beautiful birds represent a particular way that we can relate to our mental and spiritual poisons.

In the Vajrayana tradition it’s said that there are three ways of dealing with proverbial poison. The first, which is arguably the least dangerous option, is to avoid it. If you have a poison tree in your yard, chop it down. If you feel rage welling up in you, refrain from venting it. And if everyone else is drinking scotch, order apple juice.

But poison—if used correctly—can be a medicine, so maybe you’d like to put your axe down and let that tree in your yard live. It’s important to remember, though, that you must be skillful to employ this method or else you simply end up poisoned. If you want to use the leaves of the poison tree as medicine, you need to know the correct dosage to use and the right time to take it. And if you want to use your so-called vices and unwholesome mental states as the path to enlightenment, you really need to know how to transform them.

To the peacock, poison is no other than nourishment.

Finally, in the third way of dealing with poison, we take a page from the peacock’s playbook. The peacock struts over to that tree in your yard and just gobbles down a whole venomous branch because, to the peacock, poison is no other than nourishment. It’s what creates the brilliant plumage.

Tenzin Wangyal, a lineage holder in the Bön Dzogchen tradition, puts the peacock’s method into spiritual terms: “Instead of avoiding or manipulating poison, you host the poison. You bring naked awareness directly to the pain or poison, and discover that the true ground of being has never been poisoned. In so doing, the pain liberates by itself.”

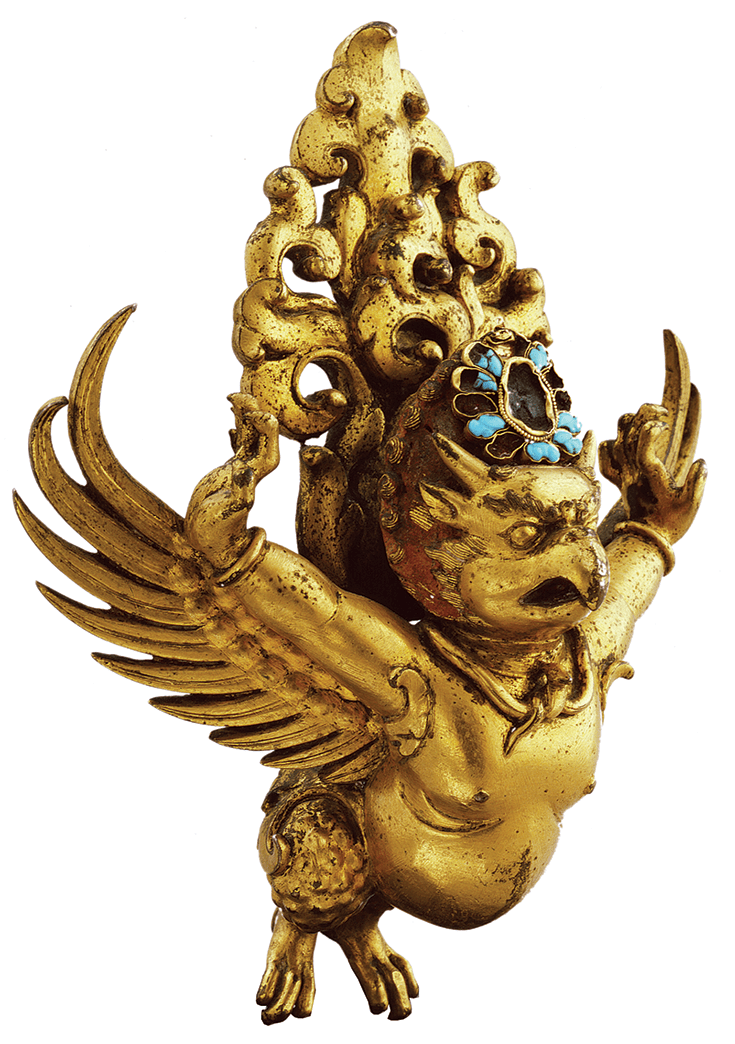

The Bird That Stormed Heaven

Fabulous and fantastical, Garuda is the lord of birds in both Buddhist and Hindu traditions. According to legend, Garuda had a five-hundred-year incubation and then hatched fully formed. His golden body was so luminous that he was mistaken for the god of fire and his wings beat with such vigor that the earth shook.

One day, Garuda’s mother Vinata and her sister had a disagreement about the color of a horse’s tail, and apparently this sister was quite testy, because to get revenge she kidnapped Vinata and held her ransom in a serpent-pit prison. Amrita, the nectar of immortality, was to serve as payment, and Garuda—desperate to free his mother—stormed heaven to steal it.

Because Garuda hatches fully mature, he represents the Vajrayana view that enlightenment can happen fully on the spot.

After that, however, things did not go quite as planned. Through subterfuge, Garuda completed his rescue mission, but the gods were hot on his heels and they eventually—with enormous effort—pried the amrita from his beak. In the fray, a few drops fell on some sharp blades of grass, and serpents licked these drops up, forever forking their tongues. Moreover, the god Vishnu managed to subdue Garuda and, taking him as his vehicle, granted him immortality.

Originally, Garuda was always depicted straightforwardly as a large, powerful bird. Later images, however, show him as a “bird-man.” In Tibetan iconography, he has the torso and arms of a human, yet his thighs are feathered and culminate in talons and he has the fierce head of an eagle. It’s said that his two horns symbolize the two truths, relative and ultimate, while his two angelic wings symbolize the union of method and wisdom. Because Garuda hatches fully mature, he represents the Vajrayana view that enlightenment can happen fully on the spot, without a long gestation. Because he extends his wings without limits and soars fearlessly into space, he represents absolute confidence.

As the lord of the skies, Garuda is traditionally seen as an enemy of the lion, the lord of the earth. But in the Tibetan imagination, the rivals mate and give birth to a beast that has the body of a lion and the wings and horns of Garuda. A symbol of the union of earth and sky, the Garuda-lion is one of what are called the three victorious creatures in the fight against disharmony. The other two are also born of animal enemies. The fish-otter’s body is covered in the sleek, dark fur of an otter, but at the neck this fur gives way to scales. The makara-conch, on the other hand, is a dragonish water-monster, with its head and mane bursting from a spired shell.

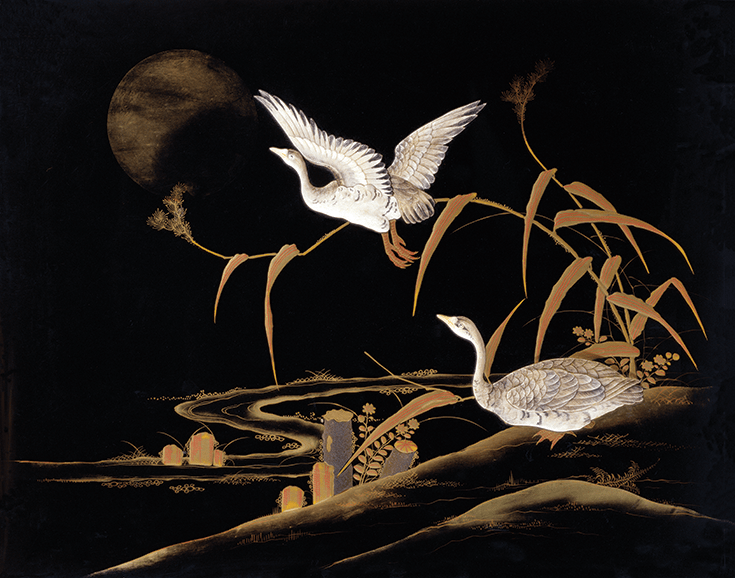

Ikkyu’s Crow

There is only one thing more magical than wildly impossible avian-mammalian hybrids—an absolutely ordinary bird. In 1420, Ikkyu, the celebrated Zen master, poet, and troublemaker, was meditating in a boat on Lake Biwa when he heard a crow cawing and found himself rattled into satori, an experience of enlightenment. “One pause between each crow’s/reckless shriek Ikkyu Ikkyu Ikkyu,” he wrote. “No nothing/only those wintery crows bright black in the sun.”

Beyond being a pretty symbol, beyond being a character in a morality tale, birds are just what they are and they can reveal to us what we are. “All I am is the birds singing and fluttering,” said the late meditation teacher Toni Packer. “Birdcalls and the songs of the breeze do not exist when the mind is full of itself.”

Do you remember that dark, glossy creature that, for me, made a nest in the four noble truths? Well, almost as soon as class let out I found a friend who could tell me about my mystery bird, and at first I was disappointed by what I learned.

It was a European starling.

That is, of course, a lovely name. It has all the ancient allure of the Old World, plus—with a star—it’s almost celestial. But European starlings are worse than ho-hum common birds; they’re an invasive species stealing the nest holes of purple martins and swallows and nuthatches. They were introduced in 1890 when some hair-brained humans decided to release sixty of them in Central Park because they wanted all the birds mentioned in Shakespeare’s collected works to fly free in North America. Now, from Alaska to Central America, European starlings are perched on garbage cans pecking at moldy sandwiches; they’re mobbing lawns; they’re shitting dirty white on shiny cars. But this, all the same, is the truth: Sometimes—even if it’s just for a moment—they still wake me up with their unmusical song.