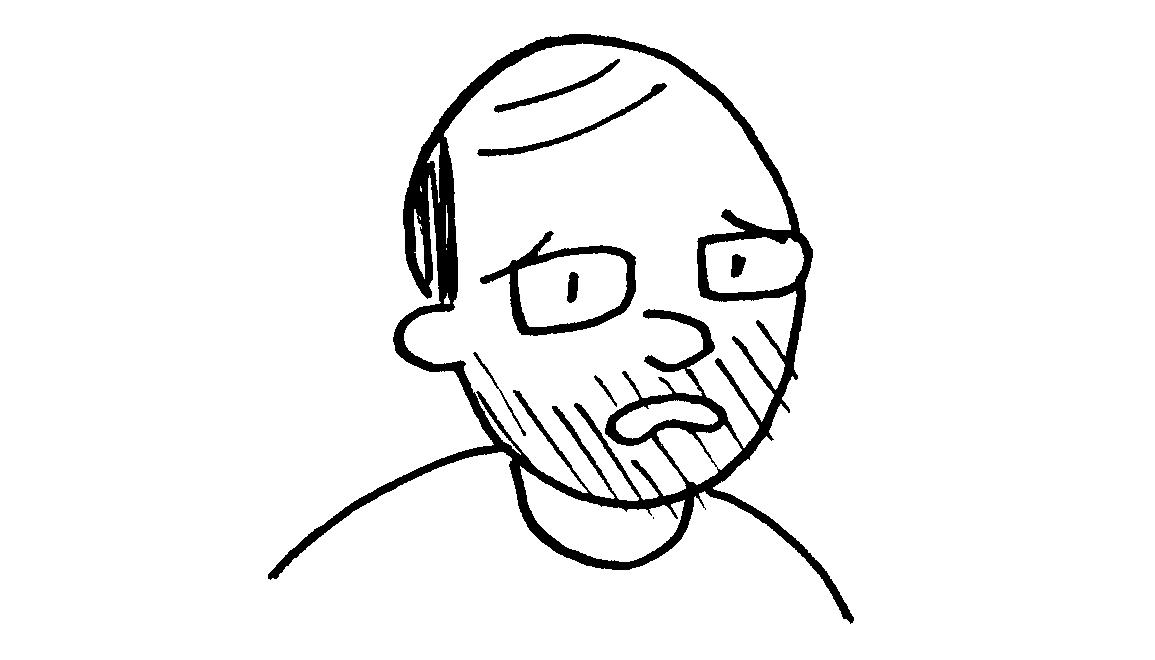

Buddhism has texts and art – but what about comics? John Porcellino is a pioneer in the self-published comic industry, an outspoken voice for DIY ethics, and a practitioner of Zen Buddhism.

Porcellino has been self-publishing and distributing his famous minicomic series, King-Cat, since 1989. King-Cat is serialized autobiography that captures the “moments-between-moments” of everyday life, in heartfelt and humble stories. His critically acclaimed graphic novel, The Hospital Suite, tells the story of his struggles through physical and mental illness. Spit and a Half, his zine distribution company, helps self-published artists find a community. For Porcellino, all of his occupations come together in the practice of Zen. As he puts it, “Buddhism includes everything, like punk rock, groundhogs, and comic books.”

I interviewed Porcellino about how Zen influences his creative work and how practice has helped him work through mental illness, and where exactly comics, punk, and Buddhism intersect.

Lauria Galbraith: How did you get introduced to Buddhism?

John Porcellino: In the mid-nineties, I began to have some mysterious health problems that made me reassess my life, which — up to that point — had been a life of playing in loud bands, eating Burger King, and drinking a lot. I’d been a spiritual person my whole life, but in a vague way.

Even before my work was Buddhist, it was Buddhist.

When I became sick, I read an old beat-up paperback that I’d found in my dad’s closet called How the Great Religions Began. I became very interested in Hinduism and Buddhism and began reading a lot about the two. Eventually, the simple rigor of Zen became more and more attractive.

I started meditating, but with no real cohesive practice. A few years later I read Opening the Hand of Thought, by Kosho Uchiyama Roshi, and I thought, “If this is Soto Zen, then I’m a Soto Zen Buddhist.” It just drew me in completely and I knew that I had found my way. I began looking for a teacher, which was tough because I have a general distrust of groups. Eventually, I found Susan Myoyu Andersen Roshi, and I studied formally with her for several years.

I want to ask about your background in the punk scene. There are many Buddhists who are connected to the punk community, like Noah Levine and Brad Warner. Is there something common to punk and Zen that brought you to these communities?

Yes, for sure! I think punk, at its core, is about learning to see reality for what it is. Through punk, you learn to see beyond the veils that we drape over existence, without sugar coating or making it worse than it is. It’s about going against the general grain of society, because the general grain leads to laziness, greed, and selfishness.

Additionally, punk is a DIY movement. You learn to take responsibility for yourself and your actions — but to also include the health of the community in your decision-making. Finally, punk teaches you to accept yourself and your flaws, and even to turn those flaws into sources of power. Punks find beauty in the forgotten parts of our world — in the concrete underpasses, drainage ditches, and back-alleys. These are all things Zen has taught me, too.

You’ve been doing your famous autobiographical minicomic, King-Cat, for nearly thirty years now; it seems like it’s very deeply intertwined with your life.

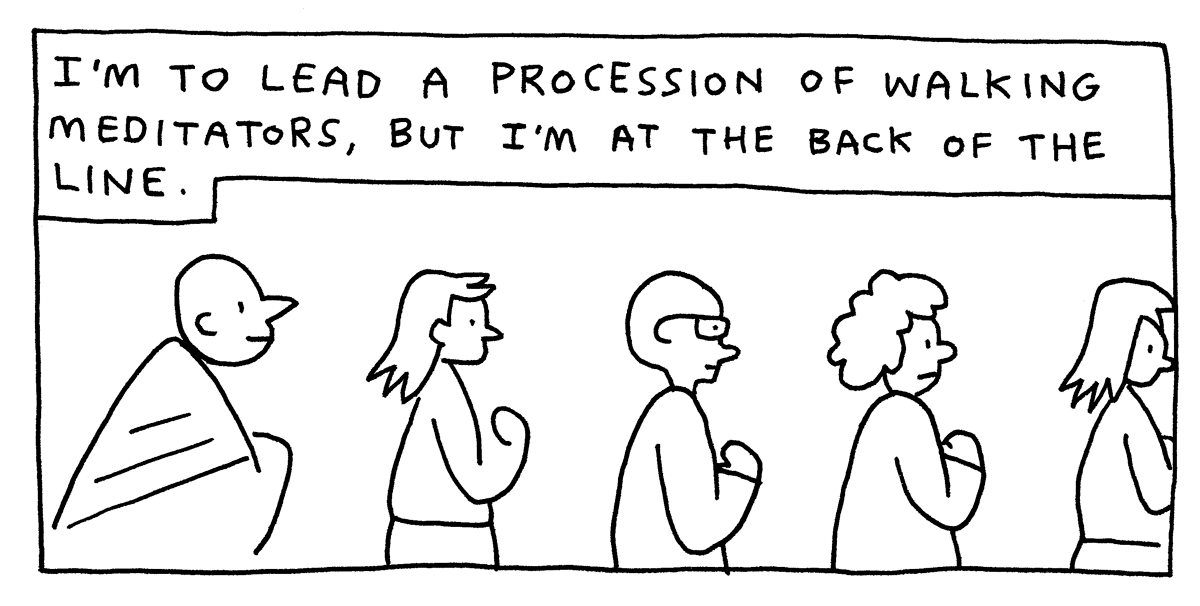

I work on King-Cat every day. That is, even when I’m running errands or doing the dishes, in the background of my mind I’m unconsciously developing my comics. All of my life goes into King-Cat.

I’ll sometimes say King-Cat used to be something I did for fun, then it became something I did, then it became what I did. At some point, there was no division between my creative life and my ordinary, everyday life. It was all part of one larger whole.

Has creating comics gotten easier over the years?

In some ways, yes. When I first started making comics there was no real deliberation to them. I just had an idea, or an experience, and almost immediately put it down on paper. There was no real editing or revising. So that was pretty easy!

Things got hard for a while when I developed Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. The OCD made it hard to do just about anything without a great deal of mental suffering. Whatever I focused on, the OCD focused on – so when I focused on my comics, the OCD did too, and it made being creative extremely difficult.

Luckily, after 10 years or so, I’ve got things worked out to where the OCD has a much lighter effect on me. In the past few years I feel like I’ve been relearning how to make comics, in light of my experience with mental illness and what it taught me. I’m trying to find a middle ground between the spontaneity of my early work and the precision of the OCD years.

There is definitely a noticeable change in your King-Cat comics over the years. A quietude has set in; the line work is sharper, and the art focuses more on absence, rather than needing all these fine details in every scene. How do you feel about its progression?

I never actively tried to change anything. Any evolution was just a natural progression that occurred over the course of time. From the beginning, my goal was to try to let what was inside me come out as naturally as possible. At the start, I wouldn’t even go back in to edit my comics, or correct mistakes. If anything, I’d scratch out the mistake and keep going. I was interested in spontaneity, open exploration, and trusting my instincts wherever they took me.

When you can take a breath, remember who you are and what you’re trying to accomplish, it gives you the strength to face your demons.

When you do something year in and year out, you naturally get better at it, figure things out, develop. So likely my comics were naturally becoming a little more refined… but when I came down with OCD it really put the final kibosh on that earlier spontaneity. I spent more and more time on the writing of my comics, breaking them down like poetry, fiddling with syllables, and pulling my hair out over little details I never would have noticed or considered in the past. It got tricky: where did the artistic process end and mental illness begin? But even that I just viewed as the natural progression of my work. When I started making comics I didn’t have OCD, and then I did. I just kept making work, adapting to whatever life happened to throw my way.

On your website, you cite Zen koans as a personal inspiration. There’s certainly a Zen flavor to King-Cat – a depth in simplicity.

Well, the Zen teachings and texts have had a big influence on me. Before I discovered Zen, I was still fascinated and drawn to an exploration of everyday life. Since I was little, I felt a mysterious energy percolating behind the scenes of my life — a tip-of-the-tongue feeling. But, when I looked for it, it slid back into the shadows. That feeling — understanding it, developing it — was what motivated me in my life, and in my art. When I found Zen, I found a way to articulate these feelings I’d had since I was a kid, a structured path that others like me had walked before.

You have an amazing way of creating scenes in King-Cat that address very pure and difficult emotions.

All art forms have their advantages and disadvantages. Comics have the advantage of using words, which can be very precise, alongside images, which can go places that words can’t — into those nooks and crannies of nonverbal human experience and perception.

When I got very ill, the first thing I thought, naturally, was “Why me?” But just as naturally, the next thought was, “Why not me?”

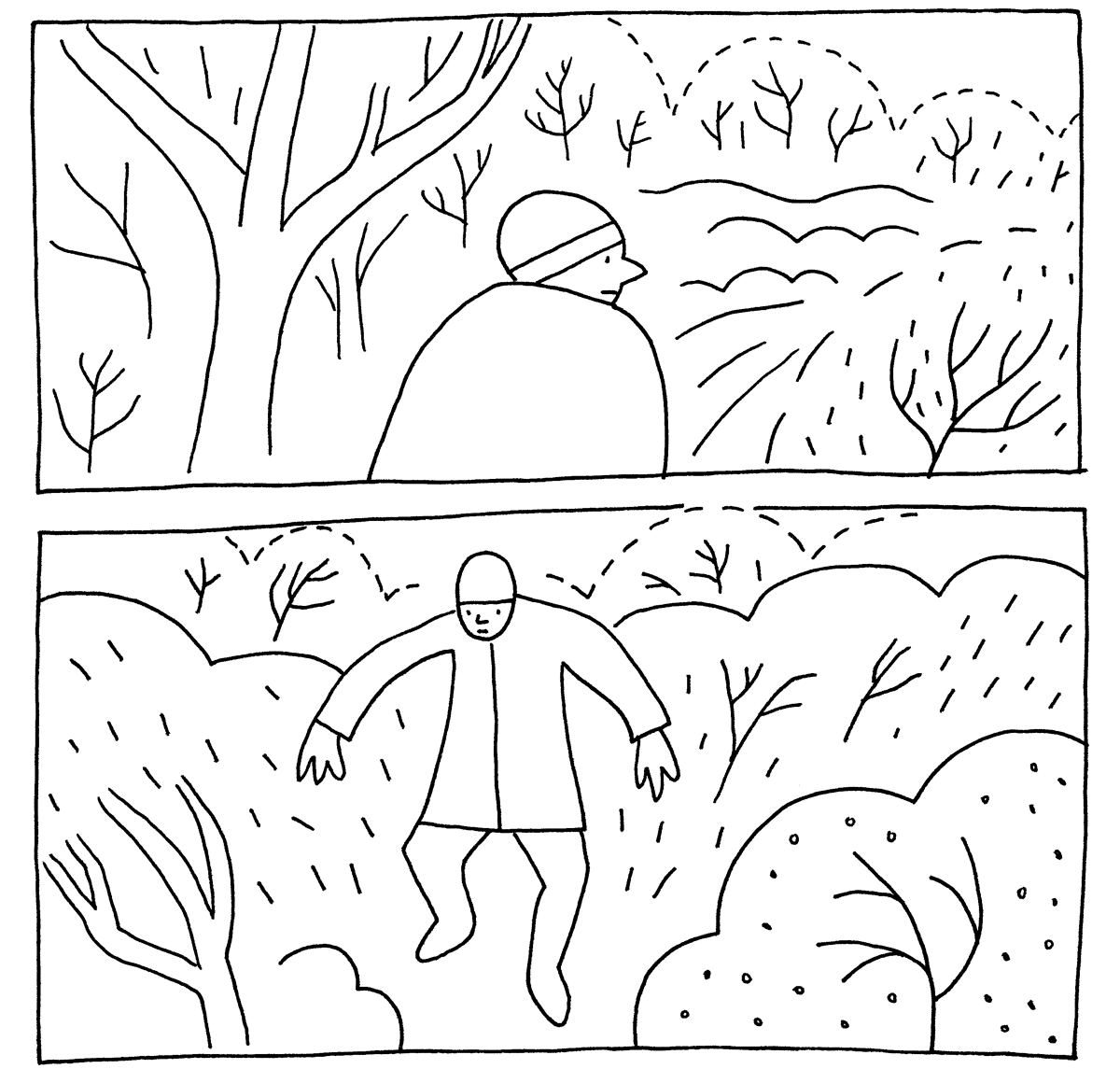

When I was drawing my Thoreau book, one of the nice things about it was I got to present Thoreau’s written philosophy (which can be quite dense textually, in that mid-19th Century way), and then, through imagery, I was able to show those ineffable, nonverbal moments and experiences that led to that philosophy. I got to show him getting stuck in the woods in a rainstorm, or quietly sitting with an owl, beyond words.

In both your autobiographical comics and your adaptation of Walden, the natural world is a prevalent theme. This is a common motif in Buddhist writings as well, particularly with Zen poets. Why does nature recur in your work?

Being out in nature was one of the first and easiest ways I found in my life to connect with something that was much bigger than my little self, but that also included me. Nature is the perfection of reality. With nature, each thing is exactly in its proper place. It’s a great teacher.

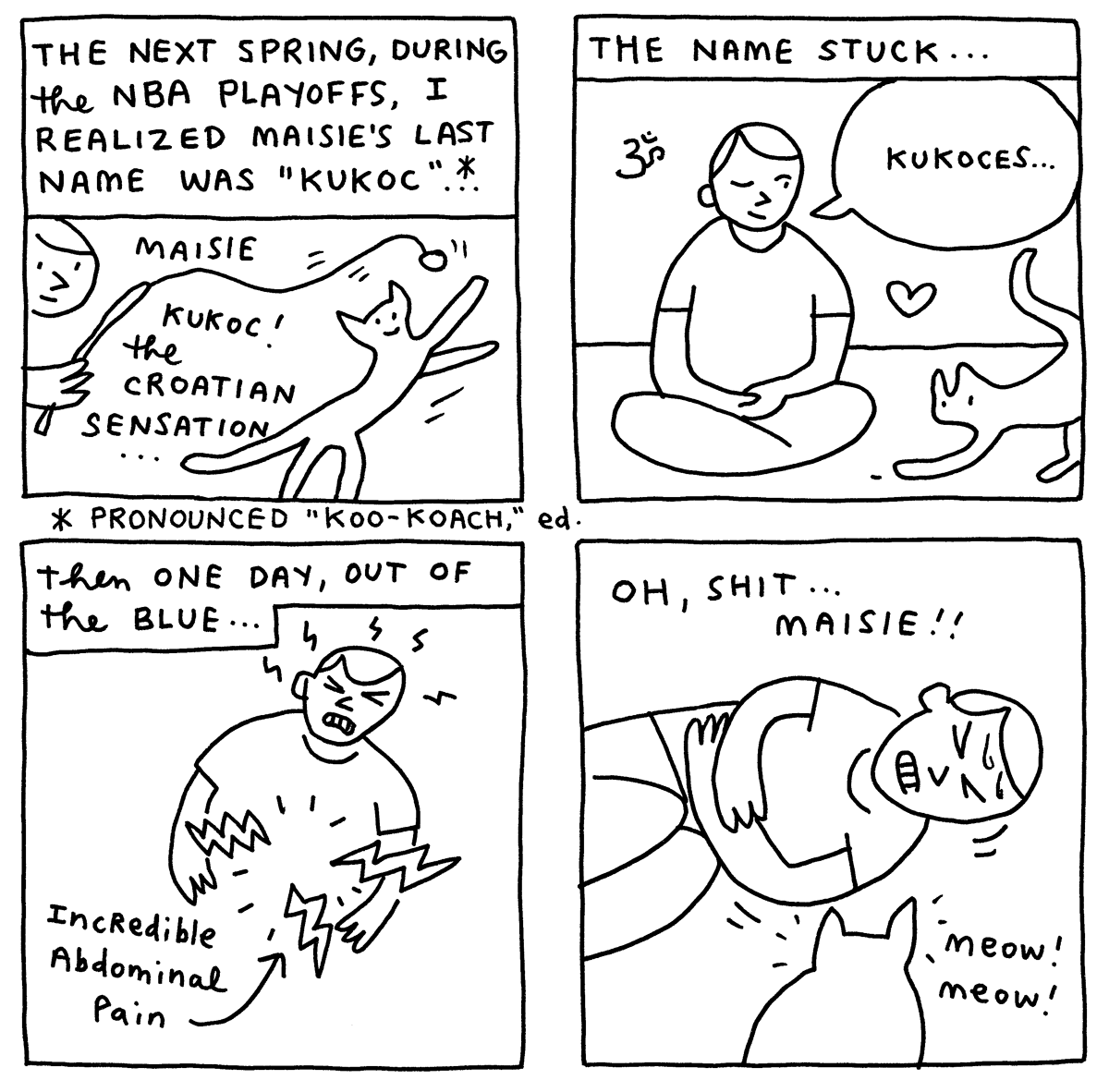

Your book The Hospital Suite covers a period of your life that doesn’t get explored in King-Cat: your hospitalization in the 90s, the subsequent deterioration of your health, and the beginnings of your struggle with OCD. Did Buddhist practice help you during this time?

Yes. During an OCD attack, you’re nothing if not lost in a very, very real-seeming illusion. Buddhist practice helps you break down those illusions, to see them as just that – illusions. To combat OCD, you have to consciously refuse to give in to it. That can be really scary. When you can take a breath, remember who you are and what you’re trying to accomplish, it gives you the strength to face your demons.

How did OCD affect your practice?

My OCD made it hard sometimes to give in. We all have resistance to practice, barriers we have to work through. OCD keeps your brain churning, and each time you think you’ve gotten past one barrier, it throws another one up in your path. Eventually, though, practice helped me deal with my mental illness much more than my mental illness hurt my practice — for which I’m very grateful.

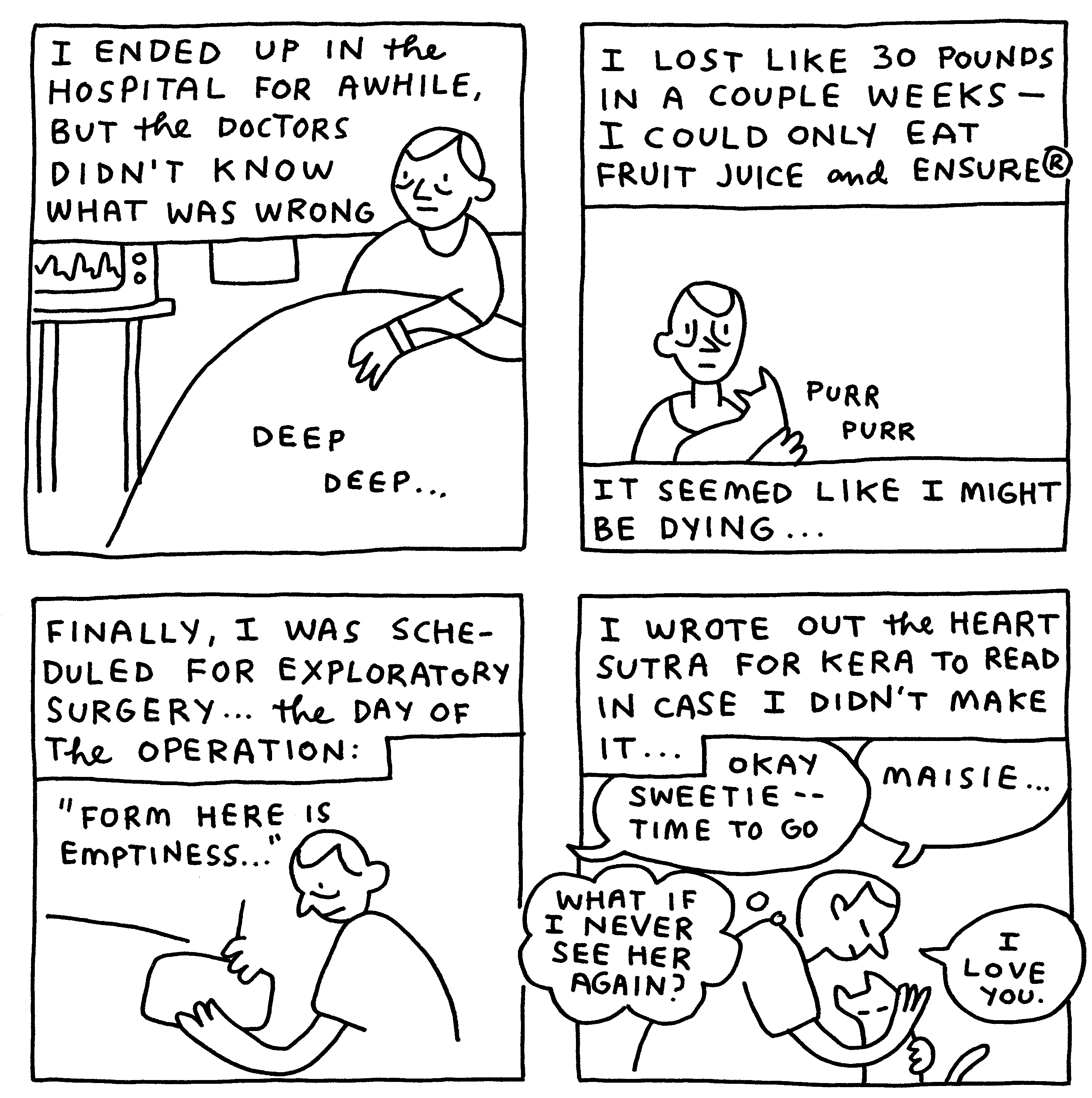

There’s a scene in the first storyline of The Hospital Suite, when you’re very sick in the hospital and in a lot of pain. You begin to recite the Heart Sutra. Why did that come to mind for you?

Well, the Heart Sutra sundered the bonds that caused Kuan Yin suffering, right? I figured maybe it could sunder some of the extreme suffering I was experiencing at the time, too! I was in terrible pain, and very frightened. It’s hard to keep your wits about you in such instances. The Heart Sutra is a plain-as-day reminder of what’s really going on. It was a tremendous balm to me.

The Hospital Suite really explores the breadth of compassion. At one point in the book, as you lay in the hospital, you remark that you’re happy that all of the nurses and doctors will gain good merit from being so kind towards you, which is such a selfless thought in that moment of pain. How did you hold onto your compassion for yourself and others during these especially painful times?

When I got very ill, the first thing I thought, naturally, was “Why me?” But just as naturally, the next thought was, “Why not me?” Terrible things happen to people every day. Why should I be exempt? I saw my illnesses in the context of my practice. They were an opportunity to explore selflessness, patience, fearlessness.

Would you personally categorize your work as Buddhist?

Sure… in the way that my whole life is Buddhist. Zen is the lens through which I view myself, my life, our world. I think, before Zen, I was stumbling through a thicket towards my destination. When I discovered Zen, it was like stepping out onto a well-worn path through the woods. So even before my work was Buddhist, it was Buddhist. Luckily, Buddhism includes everything, like punk rock, groundhogs, and comic books. So it wasn’t too big of a jump for me.

You have a new book out! What can you tell us about South Beloit Journal?

South Beloit Journal is a collection of spontaneous and unfiltered daily diary strips I drew in early 2011. At the time, I was illustrating a book called The Next Day, about people who had attempted suicide, but survived. After cutting down my paper to the correct page size, I was left with a stack of 91 little scraps of paper, just the right size for a traditional three-panel comic strip, like in the newspapers. Right about then I was at the lowest in life I’d ever been – twice divorced, completely broke, and living alone in a dreary small town in winter. I thought it might be therapeutic to put it all down on paper, without censoring myself. It turned out pretty funny.

Find South Beloit Journal and other comics by John Porcellino at www.spitandahalf.com.