For the Buddha, enlightenment—or more literally “awakening” (bodhi)—meant something rather specific. He took enlightenment from the realm of the mystics and expressed it in clear, rational, and practical terms: enlightenment is freedom from suffering.

The Buddha experienced the world as a web of interrelationships: between mind and body, senses and perceptions, actions and consequences. He saw that suffering arose from a cause, namely our own greed, hate, and delusion.

Now, it doesn’t take a Buddha to see that excessive greed can cause suffering—anyone who’s had a hangover can confirm that.

What the Buddha saw was something remarkably deep, something he described in the Nipata Sutta as “hard to see, nestled in the heart.” He saw that because of this “arrow of craving” we restlessly wander about from life to life, “seeking but not finding” relief.

Of course, suffering is not all there is to life, but it is inherent in life. Curing this kind or that kind of suffering was not his goal. He wanted to be done with all of it.

The key insight the Buddha discovered is that it is possible to let go fully of the causes of suffering. Not just a bit, not just for now, but completely, forever. Where those of lesser ambitions might be satisfied with easing their burden, setting down some of its weight, he saw clear to shedding it all.

The path to the end of suffering involves developing all eight factors of the noble eightfold path. When each factor matures in harmony and balance with the others, the mind has the confidence and strength to see through the cause of suffering and let go of it. At that moment, it is like there is a part of you that you have never seen before, and it is gone. There is a freedom and a lightness that cannot be paralleled. It doesn’t consist of anything. It just is.

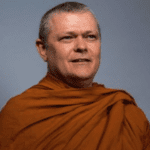

The core defilements of greed, hate, and delusion finally drop away completely at the stage of the arahant (Sanskrit: arhat), the “perfected” or “worthy” one. My first introduction to Buddhism was Ajahn Buddhadasa’s Handbook for Mankind. I remember so well how he discussed the arahant. I had never heard of such a thing before, and I was filled with a sense of wonder. How could it be that a person could be perfected and still live in this world? I guess I am still trying to answer that question!

With the ending of greed, hate, and delusion, an arahant is free from suffering in a specific sense. They still experience pain and still know the reality of the suffering of conditioned things. But they are free of mental distress, and, even more importantly, they are free from the entrapment of rebirth. They know that this is their last life.

What lies ahead for them is what we call the unconditioned state: nibbana in Pali. This is a term whose literal meaning—”quenching” or “extinguishment”—describes the going out of a flame.

A burning flame is dependent on fuel, impermanent, and painful. A flame gone out is not dependent on anything. It is cooled, stilled, at peace. For the arahant, the flames of greed, hate, and delusion are quenched, extinguished. They are cooled, stilled, at peace. They have let go of conditioned existence and are free of suffering. They are enlightened.