Buddhism began in a very simple setting. Under a sheltering tree by the banks of the Niranjana River in northern India, Siddhartha Gautama, a prince turned wandering yogi, sat steadfast in meditation until he attained enlightenment. Then, after contemplating for many weeks whether and how to communicate his transformation, he began to share the teachings that would become known as Buddhism.

Now, more than 2,500 years later, the teachings he set in motion have been faithfully documented, studied, and practiced and have taken on a variety of forms. As a result, we find a robust offering of Buddhist traditions available in the West. So much so that someone trying to get their bearings could benefit from an overview.

We can identify four major branches: Theravada, Zen, Pure Land, and Vajrayana. What ties these various heritages together and what distinguishes them from each other? Let’s begin with some geographical and historical context. Then we’ll explore various philosophies and practices—all variations on a single theme.

The Buddha’s message, uniting all forms of Buddhism, has endured and spread so broadly because it is both simple and sorely needed: There is an end to suffering. A dignified, awakened, fulfilling way of living is possible.

Following his supreme awakening, the Buddha taught for forty-five years in areas of ancient India now known as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, as well as in parts of Nepal. Over time, seeds of his universal message reached different lands and blossomed into flowers particular to their cultural soil.

Of all the branches of Buddhism currently in existence, Theravada (“the teachings of the elders”) is the oldest, and it’s also the Buddhist tradition that is most similar to what the Buddha himself taught. Theravada is widely practiced in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos, where it has mingled with local cultures, giving it a unique flavor in every locality. These iterations then became disseminated and appreciated internationally. Today, in North America, for example, the Insight Meditation tradition is a prominent movement that is deeply rooted in Theravada Buddhism.

In the centuries following the Buddha’s death, Buddhist monks and scholars developed new scriptures that expanded upon earlier doctrines. These texts gave prominence to such qualities such as compassion, wisdom, and the aspiration to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all beings. This evolving branch came to be known as Mahayana, meaning “Great Vehicle,” and initially flourished in northern India.

Mahayana Buddhism was spread eastward by monks traveling with caravans along the Silk Road and aboard ships navigating the Maritime Spice Routes. These networks facilitated the transmission of Buddhism into China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, where distinct Mahayana schools became dominant forms of engagement.

The dissemination of Mahayana texts was accelerated by the invention of movable-type printing in China, which predated Gutenberg’s press by over four centuries. This technological innovation allowed for the mass production of scriptures, surpassing earlier attempts that relied on single woodblock prints. Zen and Pure Land became the most widely known and practiced forms of Mahayana Buddhism.

A third major stream of Buddhism evolved from Mahayana as it was practiced by yogis in the northern Himalayan regions and beyond—including Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, Mongolia, and parts of Russia. This branch became known as Vajrayana, or the “Diamond Vehicle,” a name that highlights the indestructible clarity and brilliance of awakened awareness.

Although Buddhism encompasses a wide range of approaches—and interpretations of their similarities and differences vary—Buddhist scholar Jonathan Silk notes that these distinctions are “more a matter of degree and emphasis than of fundamental opposition.”

Theravada

Soon after his enlightenment, Siddhartha Gautama was given the title “Buddha,” meaning “the enlightened” or “awakened one.” This is much like how “Christ” is the honorific for Jesus.

The Buddha’s teachings came to be known as the dhamma—a Pali term meaning “universal truth.” In Sanskrit, it is rendered as dharma. His followers formed a sangha, or spiritual community, and referred to one another as kalyanamitta: wholesome companions on the path.

In his first discourse, the Buddha introduced a paradigm for liberation known as the four noble truths, which can be understood through the analogy of a medical model:

- Symptom: There is dukkha (pronounced “dook-kuh”), a state of ill-being, often translated as “suffering.”

- Diagnosis: Ill-being has a cause, that is, craving and clinging, which are conditioned by greed, aversion, and ignorance.

- Prognosis: There is a cure for ill-being. Well-being is possible.

- Prescription: The eightfold path is the way to end ill-being and cultivate well-being.

The eightfold path consists of eight interrelated factors: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. These eight elements are traditionally grouped into three overarching categories: ethics, which guides our conduct through right speech, right action, and right livelihood; meditation, which helps tame and focus our busy, restless, distracted, scattered, monkey minds through right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration; and wisdom, which fosters clarity as to the nature of reality through right view and right intention. Together, these factors form a balanced and integrated path toward liberation.

When people in the West first encounter Buddhism, it can often seem academic and complicated because it includes so many lists. But in ancient India, structured lists were teaching tools to provoke inquiry and aid in memory at a time when printed writing was scarce. They were not intentionally dogmatic. In fact, the lists were meant to inspire you to experience dhamma firsthand rather than adhere to and espouse a belief system. You could consider them as gifts to humanity made possible thanks to meditator–researchers dedicated to using their own minds as a laboratory.

If you attend a Theravada retreat today, you might be introduced to a core teaching known as the four foundations of mindfulness, a set of guiding principles for Buddhist meditation: mindfulness of body, feelings, mind, and objects of mind. These serve as a foundation for understanding the sources of our confusion and anxiety, how to unravel them, and the sublime nature of awakening. For mindfulness meditation, awareness of breath is commonly used as the entry point and anchor. When the mind wanders, you come back to the breath and the body. Just as the word “foundation” implies, you return to the ground of experience.

Another key framework for cultivation available in original Buddhism is the four boundless dwellings, divine states of being that open the heart: metta (loving-kindness), karuna (compassion), mudita (resonant or sympathetic joy), and upekkha (equanimity). The most frequently taught practice from the four divine abodes is metta, which involves instilling loving-kindness in ourselves and progressively projecting it to all beings.

The motivation of Theravada Buddhism is to liberate yourself from suffering through your own practice. Near death, as he meditated lying on his side, the Buddha told his followers not to depend on him but rather for each to be a lamp unto themselves. One Pali word says it all: Ehipassiko, “Come, and see for yourself.”

Zen

Zen lore traces its origins to a when the Buddha, teaching at Vulture Peak, held up a flower. That was the beginning and end of his sermon that day. In the crowd, a monk named Mahakasyapa smiled. In that instant, there occurred a wordless transmission of enlightenment from teacher to disciple.

Although “Zen,” the Japanese name, is the one most familiar to Western audiences, the lineage itself first flourished in China. It took root there some thousand years after the Buddha’s flower sermon, when the monk Bodhidharma sailed from India to China. He brought no books nor ritual objects—only his powerful presence and guidelines for deep contemplative discipline. In China, this lineage became known as Chan. Later it spread to Korea where it became known as Seon, to Vietnam where it became known as Thien, and to Japan where it became known as Zen.

Zen likens words to a finger pointing at the moon: useful for direction but easily mistaken for the luminous truth itself. Instead, Zen calls for both a radical understanding of our mind and the recognition that we all have buddhanature, the innate capacity to awaken. (The actuality of buddhanature is a fundamental tenet of all Mahayana paths.)

How does one come to recognize, understand, and realize Buddha mind? Through meditation! Indeed, the word Zen essentially means meditation, derived from the Sanskrit word dhyana, a term for intensive meditative absorption. Actually, Zen refers both to the practice of meditation and to the awakening that arises from it. While it shares roots with mindfulness techniques of early Buddhism, Zen places emphasis on intuitive, nonconceptual, spontaneous, direct experience.

One expression of this is the method known as shikantaza, or “just sitting”—resting in awareness without object and without striving for any particular outcome. This approach typifies the Chinese Caodong school of Chan Buddhism, known as Soto in Japan. It reflects a path of gradual unfolding, where realization is allowed to emerge naturally through sustained presence and wholehearted sitting.

An equally important Chan lineage, the Linji school—known in Japan as Rinzai—emphasizes the use of koans: seemingly paradoxical stories, questions, or statements designed to jolt the mind out of its habitual, discursive patterns of thought and facilitate seeing one’s true nature. A classic example is the question, “What is your original face before your mother and father were born?” Such inquiries defy logical answers and are meant to be lived with rather than solved. Because of their subtlety and depth, koan study is guided by a teacher who serves as both a challenger and a mirror, helping the student navigate the terrain of awakening.

Zen monastics in China, Korea, and Vietnam largely continue the custom of celibacy established in original Buddhism, while in Japan, priests, monks, and nuns can be married, an observance that has generally spread to the West.

While Zen is not wedded to a scriptural tradition, there is nevertheless a rich body of Zen literature, composed of koans and their commentaries, talks from teachers, chants, verses known as gathas, and haiku—all pointing toward liberating heart and mind. Indeed, Zen includes arguably the broadest span of cultural expressions and refinements in Buddhism, such as the tea ceremony, calligraphy, gardening, flower arranging, raku pottery, martial arts, architecture, et cetera—all reflecting a common awakened aesthetic.

Pure Land

What if one wishes for liberation from suffering via a simple path—for the benefit of oneself and others—a path in which devotion, rather than strict meditative practice, is accentuated? Look no further than the Pure Land school! Perhaps it’s best introduced with a sacred story.

Once upon a time, a monk named Dharmakara (Storehouse of Dharma) aspired to become a buddha. But rather than seeking enlightenment solely for himself, he vowed to establish a cosmic realm where all beings could attain awakening. His buddhahood would be realized only after fulfilling this vow.

As a buddha, Dharmakara is called Amitabha in Sanskrit. In China, he’s known as Amito; in Vietnam, Adida; in Japan, Amida; and in Tibet, Öpakmé. His name signifies infinite light and endless life—the highest wisdom and deepest compassion.

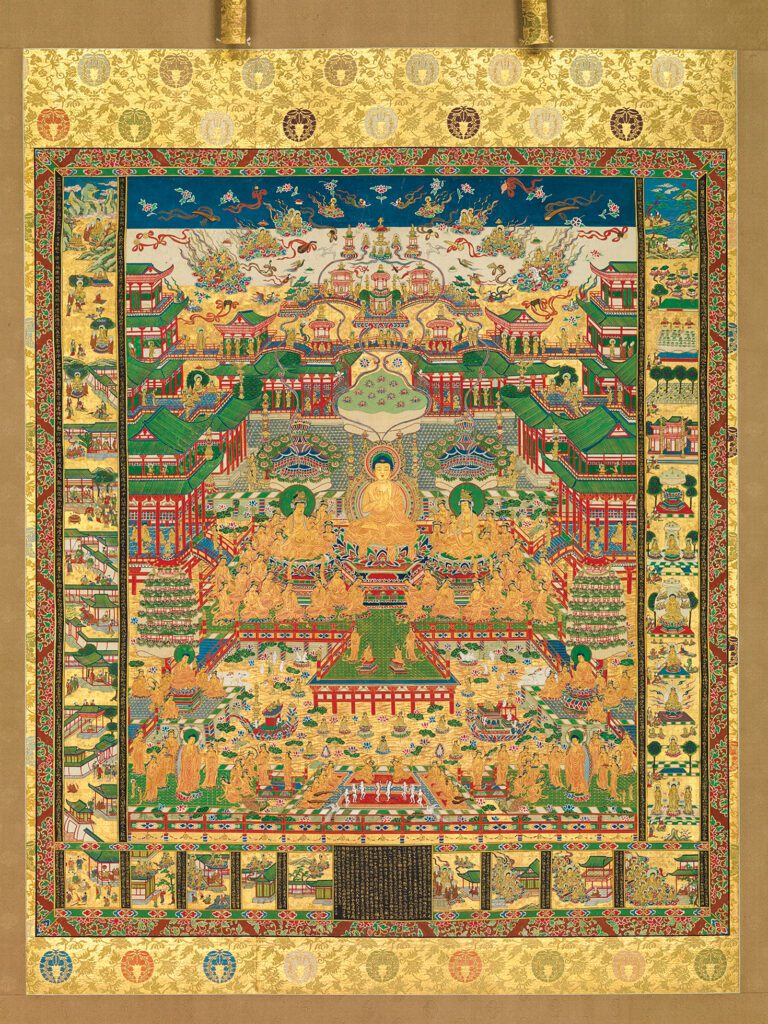

According to his vow, anyone who sincerely recites his name can be reborn in the Pure Land created through the power of his commitment. In this purified abode—a “buddhaverse,” if you will—the dharma is continuously taught, even in the songs of birds, the whisper of the wind through jeweled trees, and the murmur of streams. In short, it offers ideal conditions for awakening.

The Pure Land philosophical outlook is consistent with basic Theravada and Mahayana worldviews: Everything is interconnected and impermanent, and nothing possesses any separate, eternal identity. But one key distinction, especially in Jodo Shinshu—the largest Pure Land school—is the reliance on the power of Amida Buddha as a direct path to awakening. This is known as “other-power,” and it contrasts with the “self-power” of Theravada and Zen, which rely on the individual’s own effort.

The establishment of Jodo Shinshu by Shinran in twelfth-century Japan made Buddhism accessible to a much larger public, not just lay adherents but anyone—without regard to gender, race, or class—all of whom could recite wherever they were, as they were. All it takes is sincere recitation of the phrase Namu Amida Butsu, which means, “I take refuge in Amida Buddha.”

Interpretations of recitation vary within Pure Land Buddhism. For instance, some say that as we call to him, in this entrustment, he also calls to us. Another example is how reciting Amida Buddha’s name might be an expression of a sincere aspiration for rebirth in the Pure Land—or simply of a profound sense of gratitude to Amida and his primal vow. Then there’s the question of timing. The Pure Land is traditionally understood as awaiting the faithful after death. Others believe that a transformation of the ego might open one’s awareness of the Pure Land in the here and now.

It’s also worth noting that in cultures such as China and Vietnam, Zen and Pure Land traditions often coexist and blend as threads of a rich spiritual tapestry. A practitioner might recite the Amitabha Sutra one month, turn to the Lotus Sutra the next, and then spend a month in silent Zen meditation—blending practices in a rhythm that reflects personal devotion and cultural diversity.

Vajrayana

Just as Theravada Buddhism in South and Southeast Asia reflects influences from Upanishadic currents in ancient India, and Zen and Pure Land incorporate elements familiar to Daoist thought, Vajrayana Buddhism is shaped by Himalayan culture and the intricate tantric practices of yogic traditions. Its philosophical system builds upon key Mahayana principles: buddhanature—the belief that all beings are innately buddhas; emptiness—the insight that nothing possesses permanent, independent existence and that all phenomena arise interdependently; and compassion—the natural warmth and care for all beings that emerges through realizing emptiness.

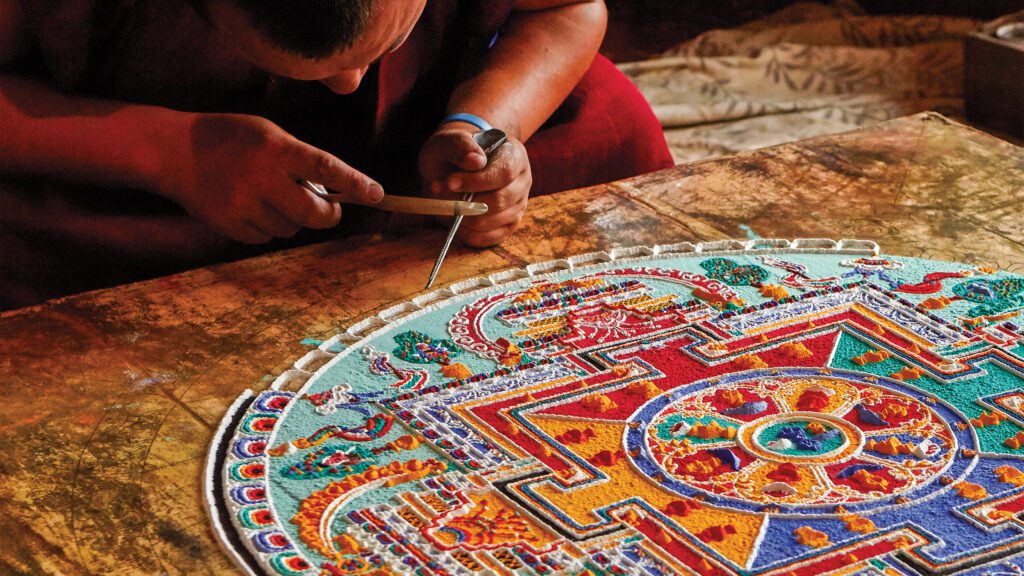

In building on its Mahayana roots, Vajrayana employs a vast array of skillful means (upaya), including tantric rituals involving visualization, mantra, mudra (gestures), music, art, and yoga. Vajrayana recognizes the necessity of a relationship with and guidance from a guru, since its practices are properly entered into only through a formal initiation from a teacher. The guidance of the teacher and fellow practitioners helps to prevent the student from straying into self-aggrandizing fascination and hallucination.

A thoroughgoing relationship with the method of mindfulness espoused by the Buddha and the vow to work for the benefit of others is essential for Vajrayana practice to achieve its objective. It is said that the most advanced practices within Vajrayana involve simple formless meditation that provokes an understanding of the luminous nature of our mind.

Buddhism increasingly contributes to the vital, contemporary movement of interfaith dialogue, which encourages welcome exchange and mutual understanding among diverse spiritual creeds. A similar vitality can be seen within Buddhism itself, through intrafaith engagement—the interaction and mutual enrichment among its various schools and practices. Exploring different branches of Buddhism is like hugging a few distinct trees: It extends our appreciation and connection to the entire forest.

At the beginning of my own pursuit, I remember how I’d see correspondences between the Abrahamic religions and Buddhism. Yet I respected differences of cultural geography and listened carefully for what might be uniquely Buddhist in each instance. This kind of attentiveness is also helpful when engaging with different paths within Buddhism, as they each have their own distinct familiarities and priorities.

When I began following the Way, in the U.S. there were more buddhas behind glass cases in museums than living masters guiding living students. But now it’s possible for anyone to take part in a range of Buddhist applications on American soil, such as starting out with Vajrayana Buddhism then continuing on in Zen, or going from Zen to Theravada, and so on. Moreover, many Americans belong to more than one lineage at the same time. As it is said, dharma doors are countless.

As we end our tour, I wish to paraphrase some words tantric master Tilopa (988–1069) has for us: “At first, your mind is tumbling like a waterfall plunging over a gorge. In midcourse, it flows on, slow and gentle, like the Ganges. In the end, it is like a vast ocean where all rivers meet, mind regarding itself, mother and child merging into one.”

Returning to where we began—namely, some 2,500 years ago—the Buddha said that the world was aflame with suffering and then demonstrated a way out. Today, in these times, it seems as if there are more flames in the world than any single mind can grasp. Luckily, humanity has been gifted with such figures as the Buddha, whom we can draw upon to help us get through, together. So, what better time than now?