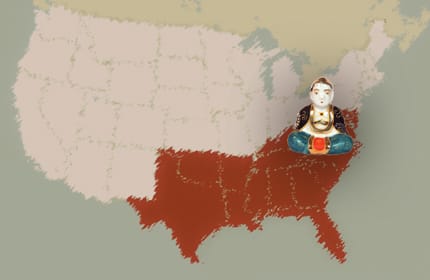

Dixie Dharma

By Jeff Wilson

University of North Carolina Press, 2012

296 pages; $36.95

The world is places,” Gary Snyder famously said. This quote from his essay “The Place, the Region, and the Commons” graces the introduction of Jeff Wilson’s new book, Dixie Dharma: Inside a Buddhist Temple in the American South. Of course, Snyder was right. We may say that we live in the world, but that “world” is only an abstract idea; we live in particular places—whether town or city, East Coast or West, the mid-Atlantic or the South. And each of these places has unique features—and cultures—all their own. This startlingly simple insight is at the heart of Dixie Dharma.

Wilson’s study focuses on a single Buddhist temple in the American South: the Ekoji Buddhist Sangha in Richmond, Virginia. It is at once a fascinating account of a pluralistic Buddhism that is emerging in the South and a troubling vision of how difficult it is to introduce Buddhist practices and ideas in a place that memorializes and celebrates its own, often erroneous, view of history.

As we know, whenever and wherever Buddhism has spread it has undergone change, adapting to its new cultural environment. In Don Morreale’s 1988 Complete Guide to Buddhist America, in an essay titled “American Buddhism,” Jack Kornfield

asks what happens when diverse Buddhist traditions encounter the American ideals of shared practice (what Wilson terms “pluralistic” practice), democracy, feminism, and integration. But Wilson isn’t especially interested in the sweeping question, “What happens when East meets West?” Instead, he asks us to consider what happens when East meets South, and he challenges us to focus a more “fine-grained attention to place… in the study of American Buddhism.”

Following in the footsteps of Thomas Tweed, his former professor at the University of North Carolina, Wilson has long been interested in the geography of religion and the importance of place in the formation of religious identity. I first came across Wilson’s writings ten years ago, when Tricycle ran a piece by him titled “Down Home Dharma.” An African-American Southerner myself, I was eager to see my homeplace highlighted. Now, Wilson’s sustained interest in Buddhism and in the South has brought us this provocative work.

Wilson’s close observations of the Ekoji Buddhist Sangha—both its literal spaces and its practicing members—shed light on how this one Southern sangha in fact consists of five different Buddhist groups: Pure Land, Soto Zen, Kagyu, Vipassana, and the Meditative Inquiry Group. These five are able to share the same physical space, the same objects, and even some practices because, as Wilson explains, they hold the view that “multiplicity may be more desirable than singularity, even when it involves certain compromises in the way that a group is able to perform its practices.” For them, “the shared label of ‘Buddhist’ is fundamentally more important than their individual differences.” (One of Wilson’s informants described this arrangement by saying that Ekoji was like “the Buddhist Confederacy of Richmond.”)

How did the members of Ekoji arrive at this pluralistic attitude? One might answer: They’re good Buddhists!

However, according to my reading of Wilson’s argument, the choice was at least partially forced upon them. The main reasons they are organized as they are has to do with where they are—that is, with the fact that they are a small center and community in a cultural and religious environment that is largely unsupportive of their Buddhist practice. Wilson suggests some other factors as well, citing a “lack of residential leaders, limited resources, low membership, and contact with other Buddhist lineages.”

For Wilson, Ekoji is thus a “pluralistic temple” where five different Buddhist groups accommodate, share with, and learn from each other. His case study is evidence of the new forms and shared practices that are indeed emerging in the South. Chanting is intermixed with silent practice; Theravadin prayers are recited alongside Mahayana texts. The same zafus serve for various sitting groups, though their arrangement in the space might differ. Still, as he also notes, while “Buddhism is not the target of sustained, serious persecution by non-Buddhists…it is nonetheless very much an outsider religion in the South.” Thus, at least some of the new forms of Buddhism at Ekoji have arisen out of necessity—a fairly common theme throughout Buddhist history.

In a chapter titled “Buddhism with a Southern Accent,” Wilson sets Ekoji squarely within Richmond’s—and the larger South’s—religious environment. While the members of Ekoji are mainly white, well off, and well educated, they make every attempt to “fly under the radar.” One member explained that this is because “most of the attendees at Ekoji feel that they are a small religious minority in a sea of conservative, potentially hostile evangelical Christianity.” This is the sad heart of the matter.

Wilson’s lengthy interviews with individual Ekoji members attest to the pressures felt by members of non-Christian practice traditions in this region. When Wilson asked the former president of the Ekoji temple what would happen if Ekoji became better known in Richmond, he answered, “We would get people denouncing us.” Another interviewee stated, “People always ask me where I go to church. I wish I could say I go to the Buddhist temple. But I don’t talk about it with my family.” One member reported, “I’m out of the closet to my immediate family and some of my extended family as a gay person, but not as a Buddhist person. I think that actually would be even more difficult for them to understand than the gay part.” Another said, “When you come from a fundamentalist Christian background, they interpret it as your decision to turn away from God, which would mean you’re going to Hell.”

I, too, have received such censure— it’s not easy to be a Buddhist in the South!

Add race to religion and things become even more complicated. Richmond was once the slave-trading hub of the colonies and, later, the capital of the Confederacy. Today, even though the inner city’s population is mostly African American—and the South lost the War!—each year Richmond celebrates Confederate Heritage Month. Wilson describes a “slave trade meditation vigil” held in 2008 by members of Ekoji and visiting Zen teacher Taigen Dan Leigh-ton, which included a modified walking meditation along a former slave-trading trail followed by several meditation sessions at the site of a slave-trade reconciliation statue. Wilson contends that this ritual provides a good case study for regional Buddhism in America, calling it a “Southern Buddhist ritual,” as if it could only meaningfully occur there. Surely, he knows better. Given the depth and pervasiveness of the legacy of slavery in the United States, such engaged and transformative rituals can, and should, be practiced anywhere in this country.

Wilson has clearly been influenced by his teachers and predecessors. For example, in Dixie Dharma one hears terms like “maps,” “boundary-crossing,” “permeability,” and “positionality”—all ideas that closely echo those found in Thomas Tweed’s Crossing and Dwelling: A Theory of Religion. (Interestingly, when Wilson speaks here of his own positionality, he tells readers that he is a Buddhist practitioner, but does not divulge information about his personal familial ancestry. One would suspect it is deeply Southern.) Moreover, because he wishes to situate his study within the field of American religious history as well as Buddhism, Wilson also tends to see parallels with that particular history. He describes, for example, Takashi Tsuji, the original founder of Ekoji, as a “Buddhist circuit-rider,” echoing the terminology and ethos of the early Methodist preachers in this country. While interesting and even entertaining, sometimes it seems to me that such analogies are stretched a bit far. And, of course, the largest issue of all: Wilson’s study focuses on a single Southern sangha, and a pretty unique one at that given that it houses multiple Buddhist traditions. There are many other sanghas located throughout the South, which may vary a great deal from Ekoji. We will have to wait for other ethnographies before we can declare a definitive Southern-style Buddhism.

These criticisms aside, I see this book as being immensely valuable. Typically, when we think of Buddhism in America or of American Buddhism, we’re thinking of Buddhist centers and practitioners found in the Northeast or along the West Coast. And though Buddhism has—especially over the last few decades—been drifting into new regions of this country, very little attention has been focused on these new sites prior to this study. The power of this book is that for the first time—through Wilson’s careful attention to space and place and region, and his thorough interviews—we are given access to the actual experiences of people practicing Buddhism in the South.