Buddhism is the shapeshifter of religions. There are some bottom-line principles — I think of the four noble truths and the three marks of existence — but beyond those it is flexible and pragmatic. Because the point is not dogma but the very practical problem of suffering, Buddhism happily adapts itself to respond effectively to the needs of different people, communities, and times. The technical term for this is skillful means.

Over the centuries, this has been Buddhism’s strength as it has moved from country to country. This flexibility is even more important in today’s fast-moving and pluralistic society. Buddhism in the twenty-first century will take many different forms, with different emphases, to meet the needs, values, and reference points of different people and communities. Here is one form it may take.

I’ve been spending time lately with people in their early twenties. I am so impressed and inspired by this generation. They are knowledgeable and thoughtful, caring in their relationships, and far more mature than my generation was at their age (or at least I was).

Service is the very Buddhist principle of helping and protecting other people, society, and the earth.

I ask myself, what can Buddhism offer these young people? What is the skillful means that will best support them and their aspirations? This is important, because in the future they will lead our society, and they can change it for the better.

As I look at this generation’s character and values, I see three principles that are important to them: ethics, service to others, and a meaningful life. A Buddhism that supports these three values will help them, us, and all of society. As this issue shows, these are core Buddhist teachings.

Today, we look at ethics in a broader, and if I may say, more sophisticated way than in centuries past. Reflecting the modern take on ethics, the Buddhist precepts about not killing, stealing, lying, etc. are now interpreted by Buddhist teachers such as Thich Nhat Hanh to include all the social, political, and environmental impacts of our choices.

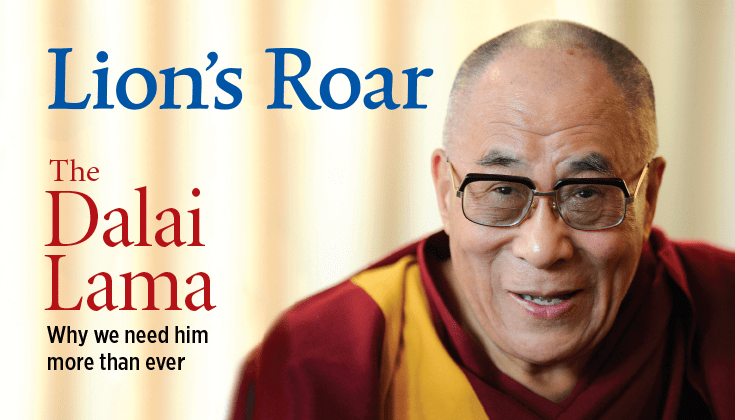

His Holiness the Dalai Lama calls this a sense of universal responsibility — that we are responsible for all others, and for the far-reaching ramifications of everything we do. This is awareness and commitment in action, demanding but vital to our future.

Ethics ensures we do no harm. Service is the very Buddhist principle of helping and protecting other people, society, and the earth.

Many young people today envision a future of service. For them, life is not about material gain. In a society that too often celebrates selfishness, Buddhism can inspire and deepen their compassion and give them the tools of mindfulness and self-care to handle the challenges of serving others.

Ultimately, ethics and service are about leading a meaningful life. This is what we all, young and old, aspire to. Our story on Robert Waldinger, Zen priest, psychiatrist, and leader of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, tells us a lot about what makes life meaningful and happy (page 34). It’s called by many names — love, compassion, ethics, service, even enlightenment — but basically the secret to happiness is our relationship with others.

Yes, Buddhism will take on many forms as it evolves in the twenty-first century. There will be many Buddhisms to meet the needs of different people, communities, cultures, and developments in the world. People will bring their wisdom to Buddhism, and Buddhism will offer its wisdom to them. It will be joyous to see its rich diversity, but I think in the end all these marvelous expressions of the dharma will come down to the same simple truth: that life is happy, meaningful, and worth living when it’s about something bigger than ourselves.