If you stopped people on the streets of Chicago or London and ask them if Buddhists are vegetarian, the most likely response you’d get is “yes.” The public perception, at least in the West, is that since Buddhism is based on reverence for life, followers of the path don’t eat animals. And while it is true that Mahayana schools often recommend a vegetarian diet, the fact is that the majority of Buddhists do eat meat.

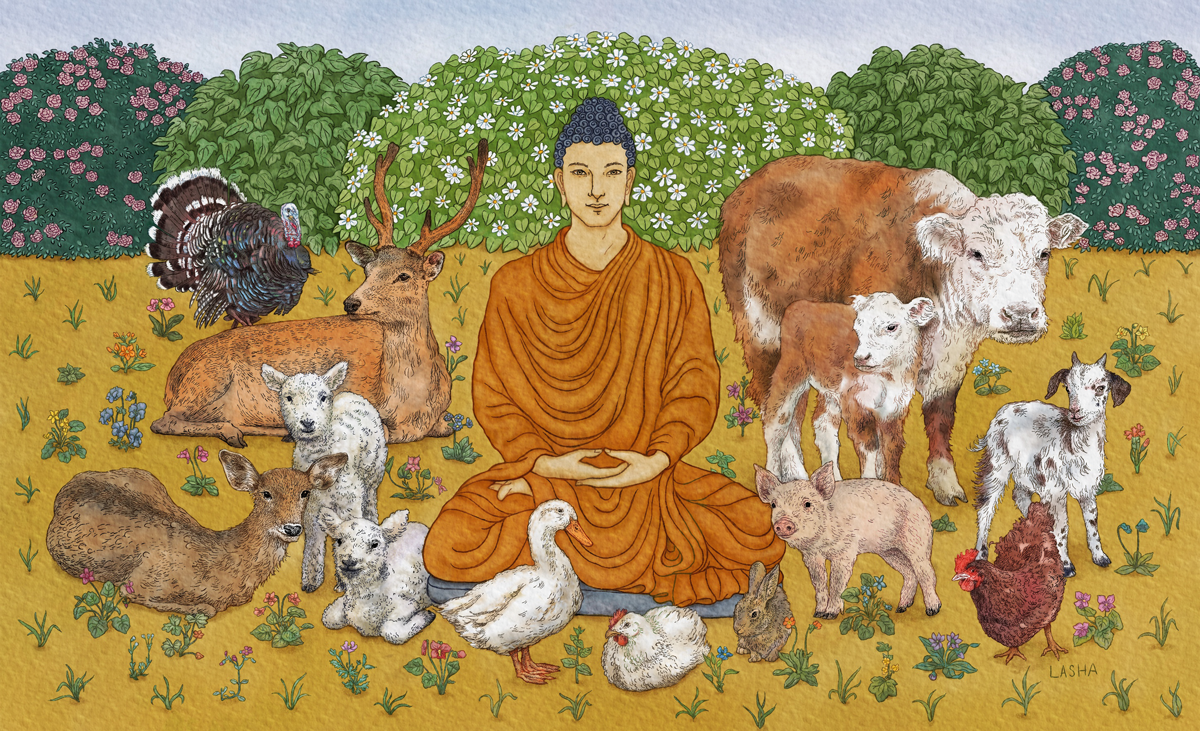

The Buddha, however, did not turn a blind eye to the suffering of animals, as many would have us believe. The first precept he taught was “Abstain from taking life.” Within this, the Buddha didn’t limit his teachings on compassion to only humans, but instead included all sentient beings—all those that can feel pain.

In the Mahayana Sutras, such as the Lankavatara, the Buddha self-identified as vegetarian and expected his students to follow his example: “If, Mahamati, meat is not eaten by anyone for any reason, there will be no destroyer of life.”

What choice should I make that avoids causing or supporting the suffering of fellow sentient beings?

In the Pali canon, which forms the doctrinal foundation of Theravada Buddhism, we find the Jivaka Sutta (Majjhima Nikaya 55) discussing “the three purities.” There the Buddha, trying to accommodate both the interdependence of the monastic and lay communities and also protect the lives of sentient beings, instructed his monastics that, when on alms rounds (begging for food), they were not allowed to eat morsels of animal flesh placed in their alms bowl if they see, hear, or suspect (a very low bar) that the animal was killed to feed them. The Jivaka Sutta does not address the morality of lay people consuming animals; therefore, it cannot be used to justify it, nor can it justify monastics consuming animals when not on alms rounds.

In order to justify their eating habits, some Western dharma practitioners like to say, “We have a choice.” Of course we have a choice in deciding whether to eat animals, but whether we have a choice is the wrong question to ask. The proper question is the ethical one: what choice should I make that avoids causing or supporting the suffering of fellow sentient beings?

Some dharma practitioners try to justify their eating habits by saying that whether or not we eat animals has nothing to do with the dharma, but since eating animals determines whether other sentient beings live or die, it necessarily lies at the core of the dharma. When one is biting into, chewing, and swallowing the wing of a turkey or breast of a chicken, one is directly and intimately involved in the death of that being. Neither the turkey nor the chicken wanted to be slaughtered and then eaten by a Buddhist. How many billions of animals will die this year to feed the approximately one billion Buddhists in the world?

Some Buddhists believe that as long as they personally don’t kill the animals they eat, there’s no problem. But in the noble eightfold path teaching on right livelihood, the Buddha listed five occupations that should be avoided, including slaughtering animals and raising animals for slaughter. By prohibiting Buddhists from raising animals for slaughter, the Buddha drew the moral line not at whether one slits an animal’s throat or not, but at whether one refrains or not from participating in a chain or process in which animals die. Those who fatten up animals for the kill and those that bite, chew, and swallow their body parts are both part of the killing chain or process. Without those eating their flesh, no animal would be slaughtered.

The actual killer of an animal is violating the first precept as well as other teachings of sila. How can a dharma practitioner eat animals knowing that the slaughterhouse workers, the ones actually doing the killings, are accumulating very powerful, unwholesome karmic effects? These workers, at least in the U.S., are predominately people of color, including immigrants, usually from Latin America, who have few alternatives and little recourse. Furthermore, slaughterhouse jobs are among the lowest paying and dirtiest in the industrialized world.

It’s better to begin taking animal products out of your diet incrementally than not to begin at all.

It’s estimated that Westerners eat ten thousand animals in a lifetime. According to a United Nations report, the meat industry causes more global warming (through emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide) than all the cars, trucks, SUVs, planes, and ships combined in the world. Production of a meat-based diet requires more than ten times the water required for a totally vegetarian diet, and farmed animals in the U.S. produce 130 times as much excrement as our human population. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the runoff from factory farms pollutes our rivers and lakes more than all other industrial sources combined.

If you’re unable to stop eating meat, chicken, and fish all at once, try: 1) eating a vegetarian or vegan diet for one, two, or three days a week, 2) eating a meat-free breakfast or lunch every day, or 3) when friends and family visit for dinner, prepare a vegan or vegetarian meal. It’s better to begin taking animal products out of your diet incrementally than not to begin at all.

The practice of not eating animals is a joyful practice of supporting life and love. It’s a practice of loving-kindness, compassion, and sympathetic joy. It’s also a practice of generosity to give life to the most vulnerable—the animals whose lives directly depend on the choices we make.

The farmed animals we eat are usually kept isolated, making it very difficult to spend time with them as we do with our dogs and cats. But when we get to know turkeys, chickens, pigs, and cows, we find that each animal is an individual with a distinct personality, preferences, and as strong a desire to live as any human. These animals are smart, sensitive, and emotional, forming bonds with one another and with human caregivers.

That animals suffer greatly on their way to our plates can hardly be denied. Since one cannot go to a factory farm or slaughterhouse to witness the terror and pain without encountering the prison-like security of barbed wire and electrified fences, watch dogs, and padlocks, it’s nearly impossible to witness firsthand the extent of the suffering. The multinational corporations that run this multibillion-dollar business don’t want the public to witness what is certainly a hell realm for animals.

Thanks to courageous women and men who, with concealed cameras, film what actually happens behind the barbed wire, a bird’s-eye view is available to all of us. If you eat animals and identify as a Buddhist, please stop for ten minutes, as a practice of the first noble truth, and watch one of these videos, such as, If Slaughterhouses had Glass Walls We Would All be Vegetarian, narrated by Paul McCartney, or Meet Your Meat, narrated by Alec Baldwin.

If you’re eating animals please understand that they do not want your metta; they want you to not eat them.