Once when the Buddha was injured by an enemy, he spent hours meditating on the physical sensations of pain, without giving in to mental or emotional distress. Finally he lay down to rest. Mara the Evil One appeared and berated him. “ Why are you lying down? Are you in a daze or drunk? Don’t you have any goals to accomplish? ” The Buddha recognized Mara and said, “I’m not drunk or in a daze. I’ve reached the goal and am free of sorrow. I lie down full of compassion for living beings.” Then Mara, sad and disappointed, disappeared.

In this story Mara is depicted as an external entity. However, I have found that the most insidious obstacle actually arises from within. It is called the Inner Critic. If left unrecognized and unchecked, it creates a pattern of negative inner comments that can undermine our wellbeing and destroy our creativity, attacking our work when we’ve written just a few sentences, sung just a few notes, or painted only few strokes. Even worse, it can destroy our spiritual practice.

The Inner Critic criticizes whatever is in front of it. For example, if you don’t go to a meditation retreat, it says, “You aren’t very serious about your practice.” If you do go to the retreat it says, “You wasted so much time daydreaming during that retreat. You should have stayed home.” A hallmark of the Inner Critic is that it often puts us in a double bind, damned if we practice and damned if we don’t.

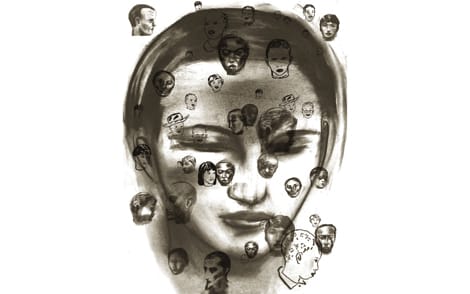

Just as the Buddha recognized Mara, we need to recognize the Inner Critic not as the truth, but as a single voice among many.

How can we work with the Inner Critic? The story of the Buddha gives us some clues. Just as the Buddha recognized Mara, we need to recognize the Inner Critic not as the truth, but as a single voice among many. You can even give it a name. “Oh, hi there Mr. Negativity. What are you so worked up about now?”

For the Inner Critic does indeed get worked up. It arises in childhood, trying to keep us from getting into trouble. It reviews our mistakes endlessly, in an attempt to prevent future errors or failures. It believes that the best way to insure our happiness is to berate us about our short comings. It doesn’t realize that it is also stealing away our innate capacity for happiness. As we grow older, it can infiltrate our mind so thoroughly that we don’t realize that we have fallen into a pervasively negative pattern of thinking about ourselves. When this happens, people begin to think of themselves as “defective” or ‘broken.”

I point out to students that they would never rent and watch the same painful movie two hundred and fifty times. And yet they allow their mind to play painful episodes from the past over and over. “Remember when you made that stupid mistake? Let’s run that mind movie again, and again, and again.” We need to tell the inner critic that we aren’t stupid. We only need to review our past mistakes once or twice, then create a determination to change and move on.

It helps to get some perspective on the damage a strong Inner Critic can do. Imagine that you heard a mother in a supermarket saying out loud to her three year old child what your inner critic says to you. “You’re an idiot! I’ve told you a million times not to do that. You’re hopeless!” We would all recognize these statements as harmful, or even abusive. No one, a child, a pet, or a plant, can thrive under that pattern of negative attack. And yet we allow our inner critic to attack us in this way, repeatedly.

The Buddha was quite clear about not giving energy to afflictive thoughts. He divided all his thoughts into two classes, those that led to enlightenment and those that led away. He cultivated the former and put aside the latter. If you recognize the Inner Critic and stop feeding it mental energy, its power will weaken.

When we can hear what the Critic says and take away the anger, the sting, the invidious comparisons of self and other, then it is transformed into the voice of discriminating wisdom and determination.

How can we cultivate a voice to subdue the Inner Critic? Through metta, loving kindness practice. We can meditate as the Buddha did, full of compassion for living beings – including ourselves. We can breathe out the silent phrases, “May I be free from anxiety and fear. May I be at ease.” We can even direct these phrases toward the Inner Critic, because this is the very part of us that is chronically anxious and fearful. It is desperately afraid that we will make a mistake, lose our job, be unloved, become homeless, grow old, become ill and die—which of course, eventually, we will.

Indeed, there is often a kernel of truth in what the Inner Critic says. Yes, I was drowsy during that last meditation period. However that does not mean that I am bad, stupid or hopeless. It just means that I had a sleepy period. Now I will drop the past and do my best during the next period. When we can hear what the Critic says and take away the anger, the sting, the invidious comparisons of self and other, then it is transformed into the voice of discriminating wisdom and determination.

Ultimately the only sure cure for the Inner Critic is to practice. The Critic relies upon an idea of a self—a small self—that is imperfect and must be fixed. It feeds on comparing, on thoughts of past and future, of mistakes and anxieties. The Inner Critic has no traction in the present moment. When our minds become quiet, when we are resting in the this very moment, there is no past or future, there is no comparing. The small self expands to become a huge field of calm awareness in which sensations, thoughts, and voices come and go. Everything is just as it is, perfect in its own place, interconnected with every other piece of the Whole. Every being also is perfect as it is, including the temporary collection of energy we call our self.

Every morning at the monastery we remind ourselves of this truth as we chant, ‘Buddha Nature pervades the whole Universe, existing right here now.” In us, as us. Nothing is broken.