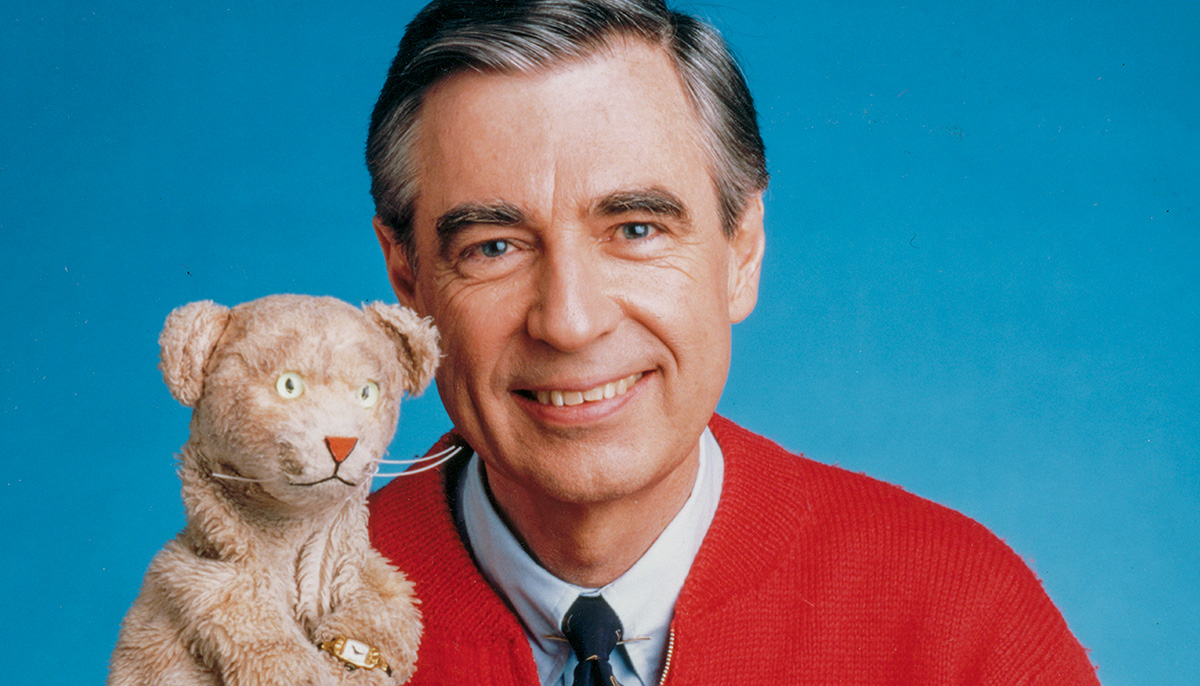

When we hear the name “Mr. Rogers,” we tend to feel warm, nostalgic, and hazy: Mr. Rogers was the soft-spoken, comforting, kinda square guy from a children’s television show that many of us watched. When we thought of him, what we probably retained were the pleasant, impressionistic memories of his sweaters, songs, and puppets.

Then the documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? arrived in theaters to give us a new perspective on a man we hadn’t thought much about since childhood, a perspective that seemed to arrive just in time for an ailing nation. Fred Rogers wasn’t just a nice man in a sweater. He was a firebrand with a cause, determined to give children the respect they deserved, determined to spread love as an antidote to hate and division, and determined to use the medium of television to change the world.

Mr. Rogers wanted us to know feelings are natural and necessary to acknowledge, and there are skillful ways to work with them.

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? crystallizes, from an adult vantage point, what Rogers was truly up to on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Though he was not Buddhist, Rogers was determined to teach what amounted to some very Buddhist values. He wanted us to know feelings are natural and necessary to acknowledge, and there are skillful ways to work with them without harming ourselves and others. He demonstrated ways to embrace those who are different from us. He preached the beauty of silence, skillful means, and fighting for what you believe in. He promoted a “radical vision of peace,” as author Michael Long argued in his book Peaceful Neighbor: Discovering the Countercultural Mister Rogers.

It’s impossible to watch the documentary without wishing Rogers, who died in 2003, were still with us to guide us through these noisy, divisive, mean-spirited times when differences are used to exclude, anger leads to mass shootings so frequent we have become numb to the news, and immigrant children are separated from their parents and kept in cages.

Rogers wasn’t Buddhist, but he was religious. He was an ordained Presbyterian minister who was so taken by the power of television — its destructive tendencies and its constructive potential — that he chose it as the medium for his secular ministry. He never proselytized on his program, but he infused it with values such as caring for the vulnerable, controlling negative impulses, and respecting others. It’s no coincidence that this led him to embody Buddhist principles, as Rogers studied all world religions in search of common themes to use in his work.

Perhaps the most classically Buddhist of his recurring themes is the value of silence. Rogers’ program moved slower than anything else on television, and he often allowed for silent stretches as he fed his fish or demonstrated a concept to his audience, making for naturally soothing and grounding spaces. But Rogers truly demonstrated that he appreciated silence as a value of its own when, in 1997, he accepted the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Daytime Emmys. Journalist Tom Junod’s famous Esquire profile on Rogers captured this moment:

“[Rogers] went onstage to accept Emmy’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and there, in front of all the soap-opera stars and talk-show sinceratrons, in front of all the jutting man-tanned jaws and jutting saltwater bosoms, he made his small bow and said into the microphone, ‘All of us have special ones who have loved us into being. Would you just take, along with me, ten seconds to think of the people who have helped you become who you are… Ten seconds of silence.’ And then he lifted his wrist, and looked at the audience, and looked at his watch, and said softly, ‘I’ll watch the time,’ and there was, at first, a small whoop from the crowd, a giddy, strangled hiccup of laughter, as people realized that he wasn’t kidding, that Mister Rogers was not some convenient eunuch but rather a man, an authority figure who actually expected them to do what he asked… and so they did. One second, two seconds, three seconds… and now the jaws clenched, and the bosoms heaved, and the mascara ran, and the tears fell upon the beglittered gathering like rain leaking down a crystal chandelier, and Mister Rogers finally looked up from his watch and said, ‘May God be with you’ to all his vanquished children.”

Similarly, Rogers worked to let us know acknowledging all feelings — good, bad, or anything in between — was a healthy thing to do, as expressed in the lyrics of his 1968 song “What Do You Do With the Mad That You Feel?”

What do you do with the mad that you feel

When you feel so mad you could bite?

When the whole wide world seems oh, so wrong

And nothing you do seems very right?

It’s great to be able to stop

When you’ve planned a thing that’s wrong,

And be able to do something else instead

And think this song:

I can stop when I want to

Can stop when I wish

I can stop, stop, stop any time.

Rogers also fought for a number of causes, including funding for public broadcasting, respect for the disabled, and equality among races. In essence, he embodied Buddhism’s noble eightfold path, making his right livelihood by soothing our troubled young souls.

Rogers’ sure and true devotion to the highest of principles have made him a source of comfort in our tumultuous times, more than fifteen years after his death. His words of wisdom often circulate online with each major public tragedy: “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’ To this day, especially in times of ‘disaster,’ I remember my mother’s words and I am always comforted by realizing that there are still so many helpers — so many caring people in this world.”

We need Fred Rogers — still, more, again — and that’s evidenced by the Rogers Mania that began with the documentary and continues on as Tom Hanks stars as Rogers in the film A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood. Several new books about him are emerging, with telling titles such as Kindness and Wonder: Why Mr. Rogers Matters Now More Than Ever by Gavin Edwards and Exactly as You Are: The Life and Faith of Mister Rogers by Shea Tuttle.

That seems like a good sign. Mr. Rogers’ calming energy will once again serve as an antidote to the violence and division that permeates our culture, his energy further proving that not all bodhisattvas wear robes. Some wear sweaters.