Perhaps you’re stressed. No doubt this is the age of stress. Fortunately, there are many things you can do about it. Among them, a number of styles of meditation will help to slow things down, give you a bit of space, a moment of calm in the storm. There sure seem to be a lot of storms that need calming. So it’s natural that many are turning to meditation as a significant help toward mental and physical well-being.

Of course that’s not the only reason people turn to meditation. Nor is it even the most important. Perhaps you’ve experienced some spiritual question. Maybe you have a sense there’s something missing in your life. Perhaps you’ve noticed that whether things are going well or badly there always seems to be a hole. This longing for some sense of wholeness is what brings many to meditation.

Or maybe you’re thinking that things are possibly not the way everyone seems to think they are. You’ve noticed discrepancies between what you’ve been told and what you actually see and hear and experience. And, with that, perhaps you have an intuition that meditation of one sort or another might point you toward a deeper, more accurate take on what really is.

What is interesting is how meditation can be so important for us, whether we’re looking to enhance our well-being, hoping to get a bit of a better handle on our lives, or throwing our lot into the great exploration of this life’s meaning and purpose.

Whatever the reason we take up meditation, what I’ve found is that when we stop and look, step away from our assumptions just for a moment, and take up the spiritual discipline of practice, things do happen. It can be shocking to discover how much is in our hands. William James observed, “Each of us literally chooses, by his way of attending to things, what sort of universe he shall appear to himself to inhabit.” Synergies begin when we bring our attention to the ways of the world, and the ways of our hearts. We discover new territory and new possibility. An old and dear friend summarized this, observing how the cultivation of a “peaceful mind can blossom into a profound mind.”

Of course, there are many kinds of meditation, one or another for every purpose under the sun. Personally, I’m a bit of a minimalist. And so whatever your reason for considering meditation, maybe someone interested in minimums might be helpful to you.

Here’s what I have to offer: I find the practice of sitting down, shutting up, and paying attention is the most useful path to a more healthy life. It will help us find peace and sometimes open us up to ever deeper possibilities.

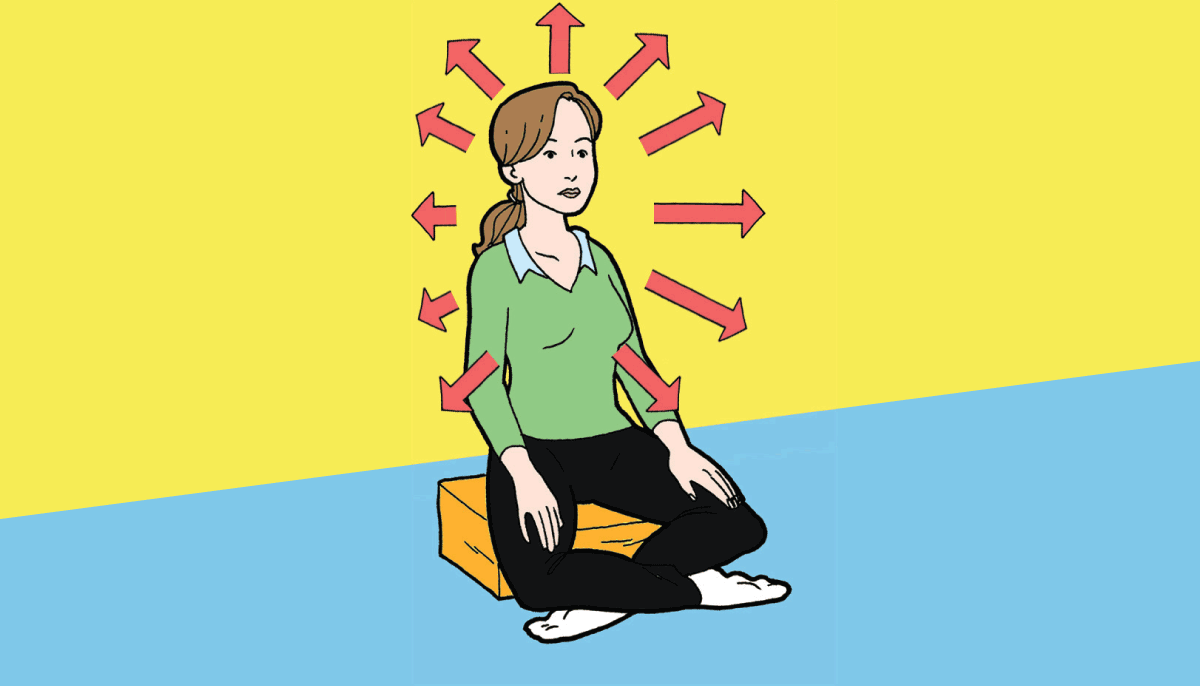

Sit down. Shut up. Pay attention. These are the points that allow the synergies to happen. As the modern Chinese master Sheng Yen said, “As the mind becomes clearer, it becomes more empty and calm, and as it becomes more empty and calm, it grows clearer.” This is the spiral path of clarity. The more deeply we engage it, the deeper we become. It is here we find that peaceful mind. With this we find the place is set where we can find a profound mind, opening ourselves to a path of wisdom in a world of confusion.

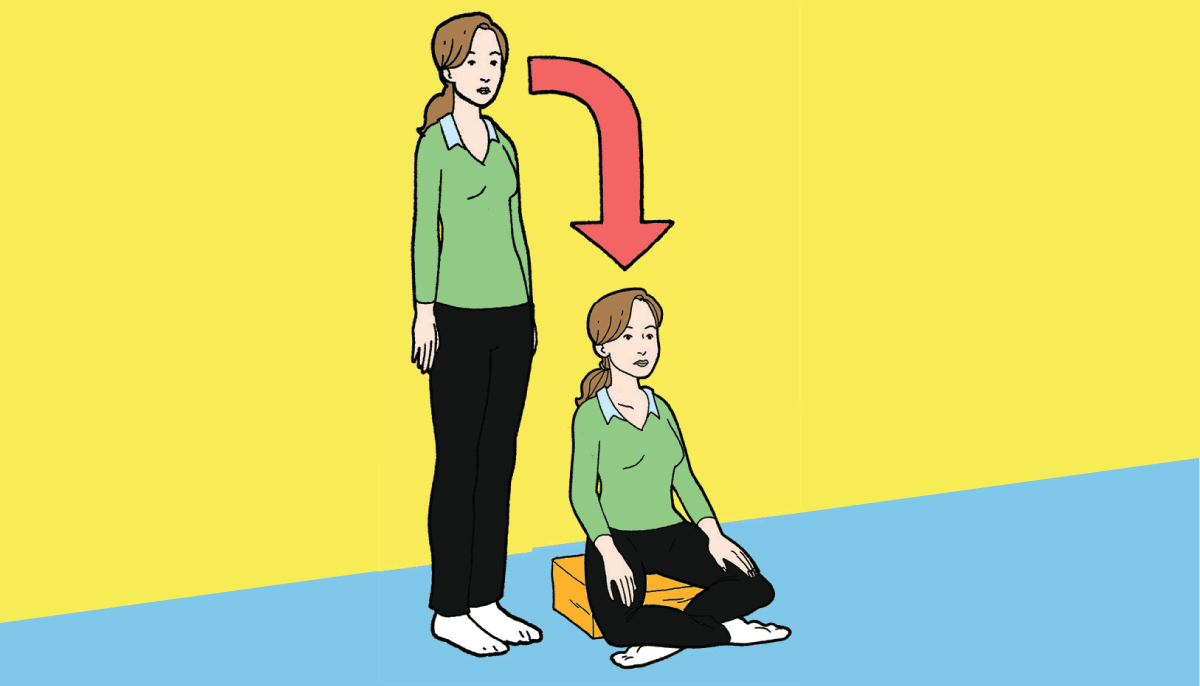

Sit Down

When I first began Buddhist meditation I met a woman who was a longtime student of Zen, and who was considered to have achieved deep insight. What is important to note here is that she was a quadriplegic; since her accident she’d never “sat” in any traditional way. Whenever I talk with people about sitting, I remember her. In fact the Buddha told us there are four postures suitable to meditation: standing, walking, lying down and sitting down. They all work. They all have a place.

That said, for most of us it seems best to begin the practice by sitting down. Taking our place this way establishes our intention and allows us to focus on the basics of the practice.

When someone says something like, “I don’t need to sit, my spiritual practice is golf” (or knitting, or archery, or target shooting), I think they might well be missing something. Now, I have nothing against golf, or any of these activities. While each of them brings gifts, true meditation—at least the meditation disciplines associated with Buddhism—bring us to something more important. And we start by taking our place, by sitting down.

Just sit. If you can hold your body upright it is better. You can sit on the floor on a pillow or on a chair. Whichever you chose, it helps to have your bottom a bit higher than your knees. This establishes a triangular base that supports your torso. Pushing the small of the back slightly forward and holding the shoulders slightly back helps create that upright position. Sitting this way, you can immediately feel your lungs opening up and each breath invigorating your body.

Place your hands in your lap. In Zen, we like to sit with our eyes open. Many traditions prefer to close the eyes. Experiment a little. Find what seems to work best for you. Personally, I like to see where I’m going.

Shut Up

Maybe you’ve heard the story of the professor who visited the Zen master. The professor talks and talks and talks, until his throat is dry. Finally the master offers him some tea. The professor thanks the teacher, who then sets out two cups and begins to pour tea into the first cup, and pours and pours. The tea flows out of the cup and covers the table.

Most of the time when people hear this story they identify with the Zen master. We all know people like the professor, people who just don’t know when to shut up. But the truth is that we’re such people ourselves. That is you. That is me. It’s a human thing.

For the most part we are running a steady commentary on life. We’re judging, we’re refining, we’re planning, we’re regretting. We tend to run tape loops around anger or resentment, around desire and wanting, around how we think things are or are supposed to be. What if we did just shut up?

In Japanese monasteries, a novice monk would have his place in the meditation hall pointed out to him and he’d just go sit there. Shutting up in the external sense would be obvious to him because in old Japanese monasteries if you got out of hand you could catch a beating. But as for handling those loops of noise inside the head, well, almost nothing is said about that.

The invitation here is not to put a complete stop to our thoughts, whether they’re those old tape loops we run over and over, or more creative and possibly even useful thoughts. Truth is, stopping all thought is a biological impossibility. But we can slow it all down. We can stop our thoughts and feelings from grabbing us by the throat.

Shutting up is the invitation.

Just be quiet.

Pay Attention

But pay attention to what? Our minds can wander, and wildly. We plan and we regret; we wish for something else. We rarely are simply present. So, how to deal with it?

Here’s a start. Take five breath cycles, putting a number on each inhalation and exhalation, counting one as you inhale, two as you exhale and so on to ten. The invitation here is to notice. When you don’t notice—and realize you don’t notice—return to one. Don’t blame yourself. Just return to one. Don’t blame something else. Return to one. Just notice. Just pay attention.

Or you allow your attention to ride on the natural breathing without counting.

Or you can just pay attention.

Many years ago there was an American who made his fortune doing business in East Asia. Financially comfortable, he decided to retire and to enjoy the fruits of his labors. Along the way he’d become fascinated with jade, and decided to learn all there was to know about it.

He hired the foremost authority on the subject, who instructed him to come to her home once a week for a tutorial. As he arrived on the first day, he was greeted and given some tea. Then the man was handed a large piece of jade, and with that, the tutor disappeared for an hour. When the tutor returned she claimed the jade, thanked the patron for his time, and told him his next appointment was scheduled for the same time the following week. The man wasn’t sure what to make of this experience, but he’d learned patience in his years in business, and deferred for the time being to the reputation of his tutor.

Sure enough, the same thing happened again the next week. This time the patron was less willing to defer, but he restrained himself, and came back for a third time. And then a fourth time. Each visit repeated itself exactly: some tea, some small talk, the piece of jade was put into his hand, and the tutor left for an hour.

Finally, after many weeks, he was once again handed the jade and the tutor departed. At the end of that hour he couldn’t contain himself any longer. Everything that had been boiling within him burst forth when the tutor returned. “I have no idea what you think you’re doing! But I’m no fool. You’ve just been wasting my time and my money. And now, to add insult to injury, this time you put a piece of fake jade into my hand.” And he was right— it was fake.

Just pay attention.

Perhaps you’re stressed. Perhaps you have some burning question about life and death. Perhaps you intuit there is something more to all this than you’ve been told.

Sit down. Shut up. Pay attention.

You never know when it will reveal what is true and what is fake.