If you’re just starting your mindfulness practice, the first thing to do is set up a good place to meditate. Choose somewhere relatively quiet where you won’t be disturbed. Although some noise is inevitable, try as much as you can to avoid music, television, or other electronic sounds, which are really difficult to ignore. It’s nice to meditate in a peaceful, harmonious atmosphere, so feel free to decorate your mindfulness space with things that please and inspire you.

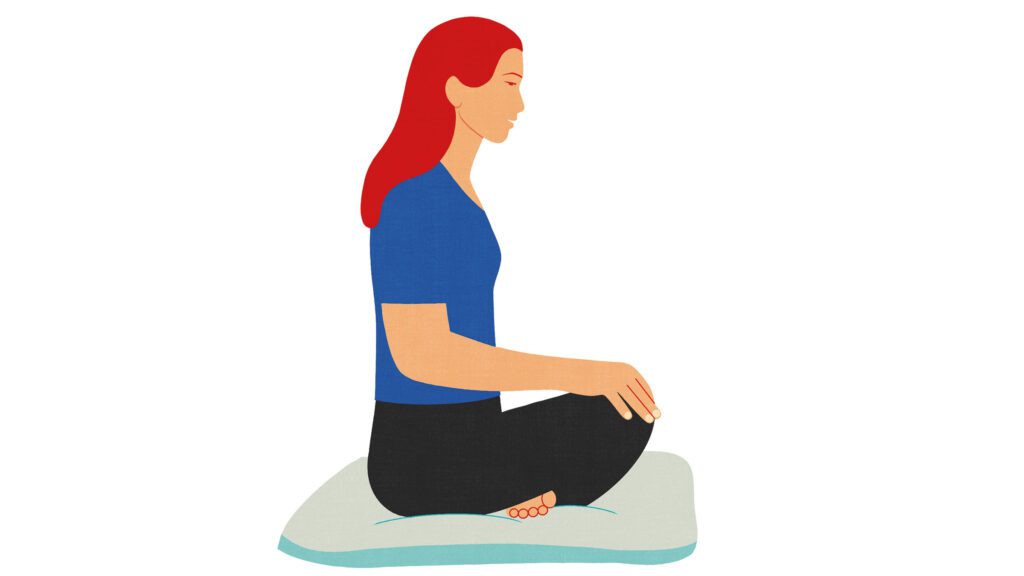

If possible, get a meditation cushion that you can comfortably sit on cross-legged. It should be relatively firm, like the many excellent cushions designed specifically for meditation. It should raise you high enough so your knees are below your hips when you sit. If you don’t have a cushion or if you find it difficult or uncomfortable to sit cross-legged, it’s perfectly acceptable to meditate on a straight-backed chair instead. There’s no need to think of that as second-best.

In mindfulness meditation you’re basically working with three things: your body, your breath, and your mind.

Your Body: Upright, Balanced, and Relaxed

Take your seat on your cushion or chair. Your posture should be upright but not uptight. You can sit on your cushion cross-legged in whatever way is comfortable (no need to force yourself into a half-lotus or some other strenuous position). Place your hands palm down on your thighs, or together at your navel, palms up with your right hand cradled in your left and your thumbs touching.

The most important thing is to have a straight but not rigid back. As you are settling into your posture, it can help to imagine that the crown of your head is being pulled gently upward, straightening and slightly stretching your spine. Your chin is tucked toward your throat so your head is tilted a bit downward. Your mouth is slightly open and your gaze is softly focused about eight inches in front of you. You are upright, alert, and relaxed. A good posture feels good.

If you’re sitting on a chair, your posture is similar: back straight, head tilted slightly down, soft gaze, hands on thighs or cupping each other. Your feet should rest flat on the floor, so the chair shouldn’t be too high.

Your Breath: The Focal Point

Now that you’ve settled into your posture, it’s time to start meditating. That makes it sound like a big deal, but all you’re doing is sitting comfortably, breathing, and paying attention. That’s it. It’s pretty much doing nothing.

The most common practice is to follow your breath going in and out. You breathe in and experience breathing in. You breathe out and experience breathing out. You can also do a little more advanced practice in which you focus only on the out-breath. You follow your breath going out and dissolving in the space around you. Then you just leave a gap and rest in openness until you focus again on the next out-breath.

You’re simply focusing on your breath as it is. You’re not altering your breath or trying to breathe in any particular way. If your breathing is fast and shallow, that’s what you experience. If it’s slow and relaxed, that’s what you experience. You don’t change or judge your breathing. Mindfulness is about nonjudgmental awareness of whatever’s happening, and that starts with your breath.

Your focus on your breathing is not too narrow or heavy-handed. While you focus on the feeling of your breath going in and out, you also remain aware of the rest of your experience—the earth below you, the feeling of your body, the space around you, the sights, sounds, and smells you perceive. Maybe you could say that 60 percent of your attention is focused on the breath and 40 percent on your environment. After all, the purpose of mindfulness is to live life fully, not narrow down your experience of it.

Your Mind: Noting Thoughts, Returning to the Breath

It may take only a couple of mindful breaths and—boom!—your mind has strayed into thinking. You’re no longer resting in the simple experience of the present moment. You’re off somewhere else, lost in thought.

You could be gone for a minute, you could be gone for half an hour, but sooner or later you’re going to wake up and realize, “Oh shoot, I got lost in thoughts.” What you do at that moment is very important.

First, you don’t go back to your train of thought. That can be pretty tempting—you could be enjoying some pleasurable fantasy, thinking up some great idea that will change the world, or deciding what you’re going to do with the rest of your day. It’s particularly easy to be sucked back into a train of thought if it’s got some emotion attached to it. If it’s generating lust, anger, fear, or hope, that makes your internal narrative more energized and sticky.

But in the end, it’s all just thinking, and where you want to be is in the real world, with your breathing and your body. You need the discipline to say no to those thoughts, no matter how real and important they feel, and return to the practice.

It helps if you acknowledge what’s happening, so it’s recommended you simply note to yourself “Thinking” or “Thoughts,” and then return to your breath. You don’t criticize yourself for thinking, or judge whether your thoughts are good or bad. You simply acknowledge them and return to the practice.

Some people think of nonjudgment as cool and emotionally neutral. But the nonjudgement you practice in mindfulness isn’t some dry, clinical examination of yourself. It’s real understanding and acceptance, the kind that only comes from a caring, friendly attitude toward yourself.

That’s why mindfulness requires a warm heart as well as an observant mind. Yes, you see your problematic patterns and the suffering they cause, but you don’t blame or criticize yourself. You’re the same empathetic and nonjudgmental friend to yourself as you are to others, particularly when they’re struggling, as indeed you are. You just gently note the patterns and return to following your breath.

You do need a lot of patience when you practice mindfulness. Because the habit of thinking is so strong in us, you’re going to get lost in thought over and over again. It’s easy to get frustrated the millionth time you mentally note “Thinking,” but don’t stop to judge yourself—that’s just more thinking. Avoid the commentary and go back to your breathing.

The good news is that if you stick to the practice, you will start to see results. As you gradually tame your wild mind, you’ll be able to stay longer in simple, direct awareness of the present moment—of your breathing, your body, and your immediate environment. Your mind and body will relax, and you’ll feel more and more comfortable resting in the moment. You’ll see that your thoughts are merely thoughts, just energy arising and dissolving. You’ll realize you don’t need to believe them, and they begin to lose their power over you.

It’s true that mindfulness practice is kind of boring. Just being in the present isn’t as entertaining as mentally travelling around the universe, or looking at your phone, for that matter. But it feels fresh, healthy, and real. With mindfulness, your perceptions are vivid, your body is in balance, and your mind is clear, uncluttered, and awake.