On the movie screen, Harriet Tubman was passionately declaring that the basic human rights and needs of Black people were not being acknowledged: “I have heard their groans and their sighs. I’ve seen their tears.” Tubman’s famous words, spoken over a century ago, resonated deeply with me so many years later.

At that time, in 2019, I was in intense negotiations to save the clinic where I had been the medical director for more than ten years. Officially, its closure would be due to “poor finances,” and “consolidating” this clinic’s population with a bigger one would balance the cumbersome, fragile budget of a safety-net medical system vulnerable to the whims of federal assistance programs and with a clientele of mostly self-paying patients. But in my heart, I knew this wasn’t the truth.

“Consolidation” is said to create stability—but for whose benefit? The answer is, for a white, dominant culture with financial security and solid citizenship. “Consolidation” is a commonly used reason to justify taking resources from communities like mine in East Lake Minneapolis, which comprises Brown, Black, economically vulnerable, and immigrant people. Consolidation is a strategy employed to mask the devaluation of Brown and Black lives. It undercuts all the reasons I made the commitment to go into medicine, to serve this community, and to help alleviate suffering.

Consolidation felt like an attack on the needs of my community, and sitting in the movie theatre that night, watching the portrayal of Harriet Tubman and her stirring words, I saw consolidation as the modern-day equivalent of suffering-making.

That movie theatre is in Longfellow, a racially and economically mixed neighborhood that feeds into the communities of Powderhorn, Seward, and South Minneapolis. Powderhorn’s urban core features Somali, Muslim, Hispanic, Black, white, and sexually diverse populations. Longfellow is lined along its eastern edge by the beautiful Mississippi River, and as you travel its bike and walking paths, you notice that the houses become progressively bigger and whiter as you approach the prettiest views by the river.

After the movie that night, I did my nightly meditation. I have been a practitioner of Zen Buddhist meditation since 2007, and I’ve served in many official capacities in the Soto Zen community—as a children’s practice teacher, a coordinator of retreats and Sunday sangha services, and as a BIPOC Zen meditation facilitator. About three years prior, I had received Jukai (the process whereby Buddhist practitioners declare their commitment to bodhisattva vows and sew a rokasu symbolizing Buddha’s robes). All of this grounded me in an active practice of daily meditation with a dedicated cushion and altar in my home.

During this night’s meditation, many questions came up—what next steps should I take and what was my role? To let the decisions about the clinic’s future be and walk away? To fight and transform? How could I save this resource of good health, connection, and safety for my beloved community?

What came to me was an image of Harriet Tubman, wading in endless water, grounded in her spiritual faith, and not giving up as she faced years of struggles ahead. It hit me as a model for what to do in my own work on the long road to saving this clinic. You could call this moment a vision, or clairvoyance, or simply the reigniting of my urge to alleviate suffering, but I needed to make sure the clinic didn’t close. It was too important to this community.

To fuel this journey, I would sit every night on my meditation cushion and feel deeply connected to those in the past who fought this fight, seeing the throughline to today. As I focused my energy this way during meditation, inspiration seemed to strike everywhere off the cushion. I would awaken suddenly in the middle of the night with a directive for action, with the perfect words for letters, or suddenly know who and what to petition next. With the enthusiasm of an imaginative clinic staff and through communicating with patients themselves, my next action or next step would always become clear.

And it worked. Through petitioning the board, writing letters of advocacy, connecting with the county commissioner and the Minnesota Attorney General’s office, we were told on December 12, 2019, that the decision to close the clinic was overturned. Our clinic would stay just that—our clinic.

We were only one month into celebrating our clinic’s survival when the waters were troubled once again. The Covid-19 pandemic struck hard and immediately started stripping resources and the usual ways of coping from our scrappy community. As was happening throughout the world, the very identity of our clinic was changed.

It was disheartening to watch this place where people could become intimately connected with their health instead become a source of fear. Our clinic also served the needs of our community in other ways, and the pandemic forced a lockout of these services. Our members were now unable to walk into the clinic to make appointments, to get advice or ask directions from the front desk, to use the wall phone to make a call. Many had limited personal phone access, made worse by mounting unpaid bills due to pandemic-related loss of work, and now they couldn’t even use public transportation to get things done in person.

Though “virtual communities” were being hailed at this time as a way to stay connected and be there for each other, most of our members didn’t have personal computer access, and libraries had been shut down. Information shared online at that time was key to knowing how to access vital resources, such as knowing the right “tagword” to get to speak with doctors like me as dictated by the latest mandates by the health department. Our community was faced with even more barriers to getting health services. All routes to communication with our patients were being shut down, and we were no longer an epicenter of health and helping. That hurt.

Part of the problem was that patients were seen as numbers by government departments, and not as the humans we knew, with faces and lovely hearts and stories that made us love them even more.

For example, we had one long-standing patient I’ll call “D” who had social phobia and childhood trauma that was exacerbated by the pandemic. She was scared witless by the fear that her sister, who worked at a nursing home and was D’s caretaker, would bring Covid into her home. D had many questions: Was she more at risk due to medical conditions related to obesity? How could she remain active while not leaving her apartment? How could she control her blood pressure that was creeping up with her rising anxiety?

D had made so many strides in the seven years of our clinic relationship. She no longer needed meds to sleep, and she was able to leave her house for a family gathering or to play with her nephew without getting severe pain or being injured. She had even started coloring and giving the results as gifts. D had relearned how to have fun.

Now we were watching D returning to her place of panic and closing up her life again. I decided that a weekly phone call from me would be necessary, and I did as much as I could to help her that way.

But just as we were adjusting and finding ways to navigate the circumstances of Covid-19 with our patients, George Floyd’s murder happened.

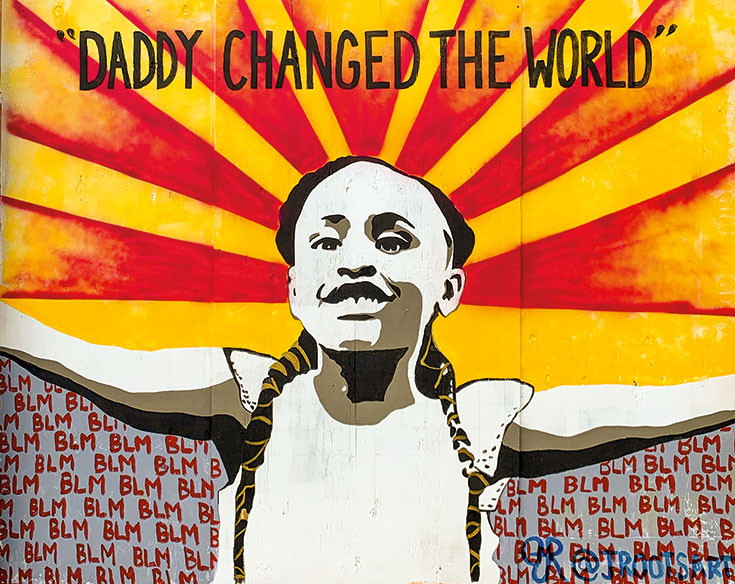

Civil unrest was everywhere, with protesters in the streets, police retaliation, and devastation. I had never witnessed anything like this before. It felt like tending to folks in a war zone, resuscitating lives in whatever way I could. The clinic was burned and became uninhabitable. During the day outside of doctoring, I was slushing through the sprinkler-alarm flooded hallways of the clinic trying to gather what was left, or picking up burnt debris in the neighborhood, marching with my community, and helping with distributions of supplies. I spent my nights combing through friends’ and acquaintances’ news and video feeds to get the real news about what was going on, because the official news stories were so different from the experience I was seeing on the ground outside my clinic. I also spent time meditating on my cushion when I wasn’t scrolling for vital updates. I needed to stay centered within myself to continue my work.

Because the clinic had been damaged so badly, it was temporarily moved into a tiny space in a larger clinic while we waited to see if ours would be repaired. Although this meant that we could now see patients, and we made efforts to keep our identity intact, some of our patients of the East Lake simply didn’t know where we were. D continued to answer my weekly call and reported being even more nervous and panicked with the state of turmoil on the streets. In spite of all this, her first words to me were, “I am so happy you are safe.”

That phrase became the mantra we all said to each other during this time. When “E,” an Ojibwe elder, was finally able to answer her phone, she said this beautiful phrase as well. E had not been reachable because the phone lines were off for more than a week. Living just blocks from the Third Precinct police station that would eventually get burned down, she had spent days hiding out in her home, not answering the door, with her shades down, instead of risking the exposure on the street to travel to join relatives in South Dakota on the reservation.

The Lopez family was so grateful for the food drives that we and other activists in the community organized that for weeks they helped clean up streets and shared their food with marchers. But they too stayed in their home to keep to their own curfew at dusk. The Lopez parents saw their work hours reduced, and experienced increased exposure to Covid-19 during the work hours they did get. They waited in lines for food donation sacks. Their children suffered as they could no longer go outside to play, and electrical outages meant digital devices were sometimes not available. Children across our community gained an alarming amount of weight due to stress eating in this fearful time, some contracting diabetes as a result.

All of the Lopez family ended up contracting Covid-19, and all they could do was hold on to each other, heal, and get back to work with the same unmitigated exposures and risks. But this determined family worked with our clinic to learn new eating habits and to start diabetes treatment for their son. That was, and is still, quite a feat.

As the unrest started to abate, wealthier areas started to rebuild. But the East Lake streets remained unsafe, the smaller businesses were still closed, boarded-up windows were still everywhere, and the beautiful bike paths were mostly unused. Those in the East Lake community were still living in rubble.

We found inspiration to keep going through community members like “M,” an older Black female preacher assistant who was committed to social order and community safety. M took it upon herself to see to the guarding, cleaning, calming, and organizing of the area where George Floyd was killed, now referred to as “George Floyd Square” by the community. M suffered headaches, spiking blood pressure, palpitations, and back pain from hours of standing in all types of weather, holding the heads and hands of distraught folks. M saw her job as a spiritual service. She stood strong in her Harriet Tubman-like presence and handed out hand sanitizer and masks to any visitor (no exceptions!) walking through this controversial area.

M and the Lopez family are some of many folks who felt compelled to take to the streets to try to help or to protest, people from all walks of life: homeless, those who drink, those more churchgoing, Buddhists, Somalis, urban food activists, anarchists, Black, Brown, white, artists, college students. Each found a role to play. But no one would come away without their own personal narratives of suffering.

In our clinic, we were finding it hard to maintain our professional stamina as we were met each day with news of unexpected deaths, heart attacks, and suicides, on top of the many Covid-19 deaths. It seemed that all our patients were surrounded by clouds of fear of displacement, illness, financial hardship, and safety concerns. Sometimes I felt like giving up. It felt like too much. Then I would think about M, or see someone on the street helping someone else. Those examples gave me the strength to continue finding ways to keep this clinic active for those who needed us.

Right now, it’s hard to say if we’re post-anything. In the East Lake community, Covid-19 rates show a higher percentage of Black people testing positive. Vaccination rates in the Black community remain lower than in the rest of the population. The effects of this pandemic still continue.

We are not post-police violence either, in spite of the conviction and sentencing of white ex-police officer Derek Chauvin. On April 11, 2021, when Daunte Wright was shot by a white police officer in the northern suburbs of Minneapolis, our East Lake community went back into hiding as army tanks rolled down the streets. Businesses once again boarded up their windows, including our clinic, as we dealt with the repercussions of another uptick in violence.

In the darkest times, the ever-optimistic M reminds us of this: “We gots nothing else but us and we everything we need.” I hope she’s right. On a walk the other day, I ran into a Black female patient I hadn’t seen in three years. She whooped and yelled, “Wow! Now I found you!” She told me how hard it had been working at her factory job, going home to her small apartment, and hearing gunfire outside on the street. She grieved the change in the neighborhood, which had been a great place to live with green spaces and relative calm. She told of her worries about contracting Covid-19 in her building, worries that made her drink more. She’d like to go fishing like she used to at the lake, but she was concerned about violence.

“So, I hole myself up at night and just sit on my chair,” she confessed. Despite the fear and losses, she then remarked how lucky she was to be here still. I replied that I felt just as fortunate. Then she said the mantra: “Yes, I am so happy you are safe.”