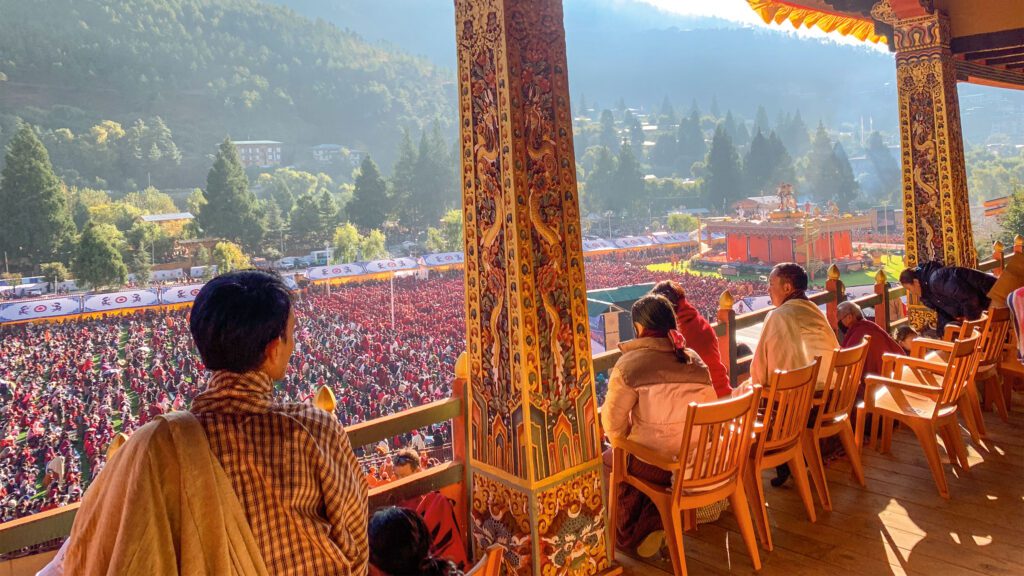

Under the bright afternoon sun, so many people are holding floral umbrellas that the crowd looks like a garden. Row after row of monks in maroon and mustard are near the pavilion where the ceremonies are taking place. In the stands behind them are lay folks, most wearing Bhutanese national dress—the women in ankle-length garments and tailored jackets, the men in striped or plaid-like robes and high socks. Topping the ceremonial pavilion, there are hand-carved wooden statues slowly spinning: the multiheaded, multilimbed Kalachakra—a buddha in union with his consort, Vishvamata, Mother of All—and a dizzying retinue of bodhisattvas. The chanting is hypnotic, melodic, low, and rich.

I only arrived in Bhutan a few hours ago. It took two days for me to get here, and I should be exhausted. Yet with all these new and color-soaked sights and sounds, I am fully awake—and a little overwhelmed.

This is the inaugural Global Peace Prayer Festival, held in Thimphu, the capital of Bhutan. The festival is a colossal undertaking—by some estimates eighty-five thousand people are taking part, making it one of the country’s largest spiritual events in living memory. On one hand, I’m here simply to witness the unfolding of the festival’s ceremonies and prayers. But more importantly, I’m here to understand how Bhutan’s ancient Vajrayana roots inform the way the Bhutanese are living today—and how they’re attempting to leapfrog into the future with their ambitious plans for creating a special autonomous region. And what does this festival have to do with it all? How is it a bridge between traditional Buddhism and a uniquely Bhutanese modernity?

Vajrayana, or tantric Buddhism, is the beating heart of Bhutan. As the country’s prime minister, Tshering Tobgay, tells me, “Our Buddhist heritage, our spiritual heritage, is the basis of our culture.”

Legend has it that in the eighth century, when the great Indian shaman and Buddhist master Padmasambhava was teaching in the Himalayas, he took flight on the back a tiger and landed in a cave tucked into a Bhutanese mountain. From there, he practiced and taught—and heralded the flourishing of Vajrayana Buddhism in Bhutan.

In the centuries that followed, Buddhist teachers from Tibet steadily streamed in. The Nyingma school, which Padmasambhava is credited with founding, took root in the central and eastern regions of the country, while various other schools developed mainly in the west. Later, the Drukpa Kagyu, a subbranch of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, gained prominence, and it remains Bhutan’s dominant school.

Today, among the nations that recognize Buddhism as their state religion, Bhutan is the only one where the state-supported tradition is Vajrayana. It is often described as the last of the Himalayan Buddhist kingdoms.

At the Global Peace Prayer Festival, it seems there’s always someone making rounds through the crowd, giving out cups of milk tea or snacks—slices of fried vegetable roll, cookies, crunchy puffed rice, or almonds. It’s a warm welcome.

A prominent Bhutanese lama, His Eminence Laytshog Lopen, said that “The festival is dedicated to addressing the pressing challenges of our time—the hardships of famine, the disasters of the four elements, earthquakes, wars, and conflicts—that continue to cause insecurity and suffering across the world.”

Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay explains, though, that it is not as if all we need to do to achieve harmony is pray for peace. The Global Peace Prayer Festival, he says, is a way to establish our aspiration. But then we need to roll up our sleeves and get to work.

Bhutan is often hailed as the ultimate land of peace, a Shangri-la. And there’s something to that. Crime, especially violent crime, is extremely low. Health care is free for all citizens. It is green and clean, the only carbon-negative country in the world. And spiritual practice is omnipresent. Children meditate in school, most families have a shrine room, Buddhist symbols adorn homes and shops, and prayer flags seem to flap in the wind at every turn.

Bhutan is known for its guiding philosophy, Gross National Happiness (GNH), which stands in stark contrast to the Gross Domestic Product that other countries prioritize. In 1972, GNH was the brainchild of Jigme Singye Wangchuck, the fourth king of Bhutan. He wanted to express the idea that there’s more to well-being than economic growth, so development should be approached holistically.

GNH has four pillars: (1) sustainable and equitable socioeconomic development, (2) environmental conservation, (3) preservation and promotion of culture, and (4) good governance. Buddhist teachings on compassion, nonviolence, and interdependence were what inspired this philosophy.

But Buddhism itself teaches that there’s always dukkha, suffering or unsatisfactory-ness. No place is perfect. Bhutan, too, has its problems, its complicated history.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the government committed massive ethnic cleansing of its ethnic-Nepali population. This involved the forceful expulsion of tens of thousands of people who were predominantly Hindu—a fact that brings up troubling questions about how cultural preservation can be used as a weapon rather than a public good.

Bhutan at that time was mired in extreme poverty and would be for years to come. The official poverty data wasn’t collected until the early 2000s, when the situation was already improving. But according to that 2003 data, 65.1 percent of Bhutanese lived below the poverty line. More than half of Bhutanese children under six were stunted, and over 30 percent were underweight. The school system was also inadequate. In the 1980s and 1990s, most Bhutanese adults were illiterate. By 2005, literacy had gone up—to a mere 53 percent.

Yet change was afoot: Bhutan was transitioning from an absolute monarchy to a democratic constitutional monarchy. This shift to democracy was initiated by King Jigme Singye Wangchuck and was brought to fruition by his son and successor, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuk, the current king.

In 2008, the Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan was enacted and GNH was explicitly referenced as a foundational principle. With the Royal Government of Bhutan recognizing that human rights are an integral part of happiness, they became enshrined in the constitution. The constitution asserts that people may not be discriminated against on the basis of race, sex, language, religion, or politics; that the Bhutanese have freedom of religion; and that it is the duty of the Bhutanese to not tolerate or participate in any inhumane acts. Abuse of women and children was specifically called out as intolerable.

In the past decades, Bhutan has made remarkable strides in improving the quality of life within its borders. That 2003 poverty rate of 65.1 percent was reduced to 10.1 in 2022. Few countries can boast of this kind of progress. The education system has likewise transformed. Literacy jumped to 67 percent of the adult population in 2017, and then it went up again in 2022, reaching 72.1 percent. Schools in Bhutan now emphasize STEM subjects and languages.

Yet the country still faces significant challenges. Pockets of poverty persist, and unemployment, despair, and out immigration are unsustainably high. It’s a brain drain: Skilled, educated, young Bhutanese are the lion’s share of those who leave.

Kalu Rinpoche is one of the teachers at the Global Peace Prayer Festival. When I interview him at his residence in Thimphu, he tells me that these days he sees his Buddhist practice as being focused on preserving Buddhism and bringing socioeconomic development to Bhutan.

“It’s important to keep the Buddhist teaching as relevant as possible, and to keep it relevant, it’s not just a philosophy,” he says. “It’s a whole economic and social structure. If you have sustainability and stability in the social order, then the Buddhist philosophy comes into meaningful effect.”

“You can do prayer from your bedroom,” he continues. “You don’t need to come to Bhutan. The real purpose of the Global Peace Prayer Festival is that His Majesty, our fifth king, wants to bring all the different sects and traditions together to build a friendship. His Majesty, the prime minister, and very hardworking civil servants all managed to invite many religious figures—not just Vajrayana masters, but also Theravada and Mahayana from Mongolia, Russia, India, China, Thailand, Vietnam, Japan, and Korea.

“The most spectacular moment was when the Hindu pundit was sitting on the shrine. That was beautiful because, when you build a strong friendship among religious figures, then you have less religious extremism. Religious extremism can happen because of two things. One is due to lack of economic development. The second is when there’s no dialogue, no friendship between religious figures.”

The organizers of the Global Peace Prayer Festival are keen for all the international journalists in attendance to meet Rabsel Dorji, chief of communication at the Gelephu Mindfulness City Authority Office in Thimphu. I’m not looking forward to this event—I’d rather be sightseeing—but Rabsel Dorji immediately draws me in.

“You’re here in Bhutan at a time of transformation in the country,” he says. “And that transformation is encapsulated by the vision of the Gelephu Mindfulness City [GMC]. It’s a royal vision to build a special administrative region in the south-central part of Bhutan, right across from Assam, India.”

The hope is that Gelephu will create a vibrant economic hub by providing a conducive business environment and compelling incentives—and that it will embed conscious, sustainable business practices. If successful, the Bhutanese hope that Gelephu will serve as a model for the rest of Bhutan, and maybe even the world.

“Bhutan is a country that’s steeped in its heritage,” Rabsel Dorji asserts. “It is also young and bold, innovative, and entrepreneurial. The GMC wants to showcase that other facet of Bhutan. We’re ready to do business.”

While this sentiment might seem at odds with the philosophy of Gross National Happiness, advocates of Gelephu insist that it is not. “We want to increase our GDP,” continues Rabsel Dorji, “but we don’t want to do that at a cost to values that are clearly part of our identity—and that’s what Gross National Happiness has always been. I like to say that GMC is the operationalization of GNH.”

With a population of around 750,000, the Bhutanese have long thought of themselves as a small and landlocked country squeezed between two giants, India and China. Now, they’re attempting a paradigm shift. What if what they previously considered their vulnerability could actually be their strength? They’re looking at the map another way and seeing that Bhutan occupies a strategic position near emerging economic corridors linking the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. If they can unlock the economic opportunities, they could cater to a catchment area of almost half the world’s population.

Not yet forty, Rabsel Dorji shares that when he was younger, he used to play a computer game called SimCity, which had him building imaginary cities completely from scratch. Building GMC is like SimCity in real life, he says. It’s a greenfield project.

As a special administrative region, GMC will have autonomy in its executive, legislative, and judicial systems, so they have to create the entire governance framework, grappling with everything from what kind of education policy and health care systems they’ll have, to what kind of investors and residents they want to attract. The planning committee is studying policies from around the world and determining what to adopt and adapt.

King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuk has what he calls a “diamond strategy” of divergence and convergence. That is, for the first twenty years, as the special autonomous region grows, Bhutan will be one country with two systems. Then over the next twenty years, they’ll gradually reintegrate. GMC will serve as a sandbox initiative, as a place for experimentation. The idea is that if they make mistakes in Gelephu, they’ll be able to quickly course correct, and the lessons learned will then be provided to larger Bhutan.

As laid out in the pillars of Gross National Happiness, Gelephu will be ecologically sound. In Bhutan it’s constitutionally mandated to have 60 percent forest cover, but GMC will have no less than 70 percent. There will be no skyscrapers. There will be low population density. There will be public transportation and walkability. GMC is going to be fueled by hydropower, solar power, and geothermal power.

Streams and rivers will be preserved, as will the elephant corridor. As Rabsel Dorji puts it, Gross National Happiness applies to animals too; it’s for all sentient beings. This is an expression of compassion and also wisdom—insight into the truth of interdependence. Human well-being depends on the natural world.

The city will have a mandala-like design. The aspiration is that Gelephu will become a leading global destination for mindful, sustainable travel and a space for all different lineages of Buddhism. Kalu Rinpoche is currently building the Niguma Meditation Institute to serve as the spiritual hub. It will have a temple with meditation and yoga halls, a library, eighty retreat huts, and an herbal garden of Himalayan medicinal plants, along with educational and treatment facilities for traditional medicine.

For GMC to work, it must continue to be very safe, notes Rabsel Dorji. “When we talk to investors or businesses or even residents, we’re able to say, ‘We know that South Asia, unfortunately, has been historically characterized by a certain lack of safety, pollution, distrust, political upheaval, corruption. To an extent, if you are a business, it’s difficult to find your way in South Asia because the enabling environment isn’t very strong. In this region, Bhutan stands out as a place of trust. So, if you want to send your children to school, if you want to do trade with larger South Asia, maybe you can use GMC and Bhutan as a gateway. You nearshore your business, before getting into the larger South Asian market, which is going to boom with huge economic opportunities in the next five to ten years.”

The goal is that Gelephu will be a catalyst for economic growth in Bhutan—and that it will bring the Bhutanese youth back home. Ultimately, the Bhutanese want to create what they’re calling “mindful prosperity,” with their culture preserved.

And they’re keenly aware that they’re not separate from their regional neighbors. “At the core of our mission statement is to make sure that the success of GMC translates to the larger region’s success,” says Rabsel Dorji. “More economic success means more regional stability, which is also in India’s interest, so we’ll be working closely with India. We will bring in many Indian companies. In fact, there’re conversations around how Assam will be a twin city with GMC.”

The city is not going to be cheap or easy to build. It will require foreign capital and laborers. And, ultimately, the aim is to have a million Gelephu residents. Even if every Bhutanese moved there, that wouldn’t be enough. They also need foreign residents.

King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuk regularly travels around the world, building new diplomatic ties, most recently with Vietnam. As Rabsel Dorji says, “GMC has opened up the doors to bring in more financial and cultural partnerships—friendships from across world.”

Midmorning on November 11, Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India, will arrive for the Global Peace Prayer Festival, and to make way for his motorcade, the road from Thimphu to Paro will be closed to traffic by 9 a.m. So, when I slip away from the festival to visit Paro Taktsang—Tiger’s Nest Monastery—I need to leave extra early.

From Thimphu, it’s an hour and a half drive to the base of the monastery’s trail. My driver takes the mountain road slowly and mindfully—as seemingly all Bhutanese drivers do.

Finally, the car stops, and I’m at the trailhead. After about forty-five minutes of making my way up the mountain, I catch my first glimpse of Tiger’s Nest, clinging precariously to the side of a cliff. It looks very far away, and I cannot imagine how I will manage to climb to it, breathing this thin, high Himalayan air.

Bhutan is known as the Land of the Thunder Dragon for its fierce, rumbling storms. But today, the sky is clear blue, a perfect partner to the expanse of green forest below. I keep going—the final approach is seven hundred stairs. I put one foot in front of the other—pause, step, pause, step—and eventually, my heart pounding, I make it.

The exterior of the monastery is at once austere and ornate with its whitewashed walls and windows of intricate woodwork. I see a sign for Tiger’s Nest and for a moment I’m confused. Aren’t I already at Tiger’s Nest? Then I realize that this is the mouth of Padmasambhava’s cave, where, it’s said, he arrived on the back of a tiger and practiced and taught. Here, right here, more than a thousand years of Bhutanese spiritual life began—and it’s still going. Who knows how it will evolve in the decades, centuries, and millennia to come?

The passage looks tight, and for a moment I wonder if the rock walls will hold. Then I shrug off that thought, and I shimmy down into the cool, dim cave.

Lion’s Roar readers curious about travel to Bhutan might also be interested our March 2026 pilgrimage. Participants will meditate in ancient monasteries, explore sacred sites, and immerse themselves in the spiritual heart of the Himalayas. Lion’s Roar would like to thank the government of Bhutan for its support in Andrea Miller’s attendance at the Global Peace Prayer Festival.