Speculations on the nature of self, other, boundary and embodiment by the great cognitive scientist and Buddhist practitioner Francisco J. Varela, written after undergoing a liver transplant.

The scene is viewed from the side. The patient is lying on his half-raised hospital bed. Tubes, sutures and drains cover his body from nose to abdomen. On the other side of the bed, two masked men in surgical outfits look at the screen of a portable scanner. The senior doctor explains and demonstrates rapidly to his apprentice, the probe searching around the right side under the ribs and over the stomach, in sweeping motions. The intern listens raptly, nodding repeatedly. The screen is turned so that the patient can also see it. It is J+5.

Five days ago, I emerged from surgery with the liver of an unknown. My attention now shifts to the two men as they speak. I follow their conversation and wait expectantly for words directed to me. It is a crucial moment: if the veins and arteries have not taken to their new place, my whole adventure comes to a halt. The graft, from their point of view, represents hardly anything more than a successful fixture. I am short of breath as I pick up the doctor’s overheard telegraphic comments: Good portal circulation, no inflammation….Abruptly he smiles to me and says, “Tout va bien!”

I am now my prostrate body. It feels broken up, in bits and pieces, aching from a visible incision that goes from right to left in an arching path, and suddenly bifurcates over the chest right to my sternum; it is almost immobile from the multiple intubations and perfusions. His reassuring statement oddly makes me feel my liver as a small sphere, as if I am carrying an infant (I remember the pictures of my last son’s beating heart in his mother’s belly); it is tinged with a light pain; it is definitely present.

In the background, the brokenness of my body beckons me with an infinite fatigue and a primordial desire to close my eyes and rest for eternity. Yet the screen is a few centimeters away and a simultaneous curiosity perks up unflinchingly. I can see my new liver, inside me. I follow the details: the anastomoses of the cava and the porta veins, the two large hepatic arteries, the II and then the III lobule squished one into the other. I travel within, gliding inside and out of the liver capsule, like an animation. I listen with unabashed interest to the explanations to the intern (“Here, look at how best to catch the flow with the Doppler”; it goes swishhh, swishhh now, as histograms display the parameters in charts and line drawings. “Here is the best way not to miss the hepatic peduncle”; this time the object is lost to me in a sea of gray).

Multiple mirrors echo shifting centers, each of which I call “I,” each one a subject that feels and suffers, that expects a word, that is redoubled in a scanner’s image, a concrete fragment that seems to partake with me of a mixture of intimacy and foreignness.

Contingency, Obsolescence

Some two years ago I received the liver of another human being. An organ came tumbling down a complex social network from a recently dead body to land into my insides on that fateful evening of June 1. My sick liver was cut from its circulatory roots and the new one snugly fitted in, replacing the vital circulation by laborious suture of veins and arteries. I can thus pronounce a unique statement (with a few hundred people around the world): I have received someone else’s organ!

Such an assertion has no echo in the past. Ten years ago I would have died rapidly from complications of Hepatitis C, transformed into cirrhosis, then rampantly turned into liver cancer. The surgical procedure is not what creates the novelty of a successful transplant. It is the multiple immunosuppressor drugs that prevent the inevitable rejection. (A code word for a phenomenon specious in itself; we will return to it.) Had it happened in ten more years it would have been a different procedure and my post-transplant life entirely different. I would surely have been another kind of survivor. In the thousands of years of human history, my experience is a speck, a small window of technical contingency in the privileged life of upper-class Europeans.

From this narrow window I must (we must) reflect on and consider an unprecedented event, one that no accumulated human reflection and wisdom has ventured into. I take tentative steps, consider everything as only a tentative understanding. I am a lost cartographer with no maps. Only fragments, no systematic analysis. We are left to invent a new way of being human where bodily parts go into each other’s bodies, redesigning the landscape of the boundaries of what we are so definitively used to calling distinct bodies. Opening up the landscape where we can borrow a piece from another, and soon enough, order it to size from genetically modified animals. One day it will be said: I have a pig’s heart. Or from stem cells they will graft a new liver or kidney and pre-select the cells that will colonize what was missing in us, in a sort of permanent completion that can be extrapolated beyond imagination, into the obscene. This is the challenge that is offered us to reflect on through and through, to give us the insight and the lucidity to enter fully into this historical shift.

My life in its contingency mirrors the history of techniques, the growing know-how about human bodies, which knows nothing about the lived-bodies that can and will come from it. Technology, as always, stands as the mediation that reveals the interrelatedness of our lives—contingencies of life that accumulate in the history of body-technologies, from antibiotics, to tailor-made drugs, to genetic engineering. All the more so now that the contingency of life, always at the doorstep of reflection on human destiny, acquires a speed that impinges even on our ability to conceive, to assimilate, to work through the ramifications. In ten years, these reflections will probably be obsolete, the entire reality of transplantation having changed the scenario from top to bottom; all the work I must do is for a little window of history before it snaps out of focus and we are to start anew.

Rejection, Temporality

I’ve got a foreign liver inside me. But: Which me? Foreign to what? We change all the cells and molecules of a liver every few weeks. It is new again, but not foreign. The foreignness is the unsettledness of the belonging with other organs in the ongoing definition that is an organism. In that sense my old liver was already foreign; it was gradually becoming alien as it ceased to function, corroded by cirrhosis, with no other than a suspended irrigation of islands of cells, which are then left to decay and wither away. Years before the transplant, during a biopsy the surgeon came to see me: “I saw your liver, it looks very sick. You must do something about it.” The statement made this silent organ suddenly un-me, threatening and already designated to be put at a distance in the economy of the body’s self. Seeing from outside had penetrated me as a blade of otherness, altering my habitual body forever.

“Self” is just the word used by immunologists to designate the landscape of macromolecular profiles that sit on the cell surfaces and announce the specificity of a tissue during development. Each one of us has a particular signature, an ecology of somatic markers. Within that landscape, the lymphocytes, the active cells of the immune system, constantly touch and bind to each other and to the tissue markers, in a tight network of two-way interaction. This ongoing mutual definition between the immune network and the tissues is the nature of this bodily self and defines its borders: not the skin, a mere thin veil, but the self-defining network of molecular profiles. The boundaries of my body are invisible, a floating shield of self-production, unaware of space, concerned only with permanent bonding and unbonding.

The self is also an ongoing process every time new food is ingested, new air is breathed in, or the tissues change with growth and age. The boundaries of the self undulate, extend and contract, and reach sometimes far into the environment, into the presence of multiple others, sharing a self-defining boundary with bacteria and parasites. Such fluid boundaries are a constitutive habit we share with all forms of life: microorganisms exchange body parts so often and so fast that trying to establish body boundaries is not only absurd, but runs counter to the very phenomenon of that form of life.

Is a graft as foreign as the rigid boundaries of a skin-enclosed boundary suggest? Conversely, what is this me that is being intruded upon? The intrusion is always already happening—the constant intrusion and extrusion dancing at the edge of a tenuous, fragile identity (my self, then), with no boundary defined except as a fleeting pattern. But the boundary is reinforced and sharply marked nonetheless, and easily irritated when the alteration is imposed too fast, too soon, too much. As when a new microorganism penetrates the mucosa, and the organism mounts an intense reaction (inflammation, fever, allergy). It is too much change, too quickly.

“Rejection,” they say. (“There’s a rejection!” The intensive care doctor bursts into my room at J+7, just as I was recovering from the trial of massive surgery, patiently recovering a sense of this placemarker called my body. I am abruptly thrown off balance. Yet, I knew about the stages of the transplantation adventure: the recovery from traumatic surgery is almost always followed by rejection, where the true danger zone begins. But in the joy of feeling more recovered, those words opened an abyss into which no sensation pointed, which showed no signs or indices, silent and imaginary in the suddenness of its irruption.) My process-identity of making a somatic home I call “self” was being thrown out; new mechanisms acquired in the Ur-ancestry of my molecular cellular environment were awakened. A whole new organ is way too much, too quickly. The ex-trusion is initiated by massive tagging of the cells marked as foreign; the cells destroyed by T lymphocytes; the new organ slowly but surely dissolved into biochemical air.

The body-technologies to address rejection are absurdly simple: disable the ongoing process of identity, weaken the links between the components of the organism. Immunosuppression is, to date, the inescapable lot of transplantation. One starts by taking special suppressive drugs and massive doses of corticoid (leaving the mind disjointed, hallucinating and with an obsessive compulsion to repeat certain inner discourses; nights spent in the corticoid desert are certainly a form of hell). As the rejection does not yield, the treatment mounts one step. I am treated with the “heavy” means, as the doctor says. As in napalm warfare, the entire repertoire of immune cells is massively eliminated by a slow injection. (As I felt the effect coming in a few minutes, my whole body was swept by uncontrollable shaking, like an alien possession that left the me (who?) in a limbo of nonexistence; looking steadily into my wife’s face, the only reference point in a disappearing quagmire.)

Complete immunosupression does stop the rejection, but now simply being in the world is a potential intrusion, as the temporality, the finitude, of my somatic identity has been erased for a few days. A new lifestyle of masks, careful watching for the slightest sign of fever and concern about opening windows, makes the body into a life of withdrawal, its proud movement and agency shriveled down.

In time, the body is allowed to reconstitute; I recover my assurance of my daily embodiment, as the immunosupression is milder. This becomes a life condition. Weakening the links that are the backbone of the temporality of the lived-body, this alteration is experienced as a newly acquired attention to symptoms, as a traveling to destinations of unknown hygiene. Immunosuppression is a walking stick; I feel the world as through an extension.

The Image, the Touch

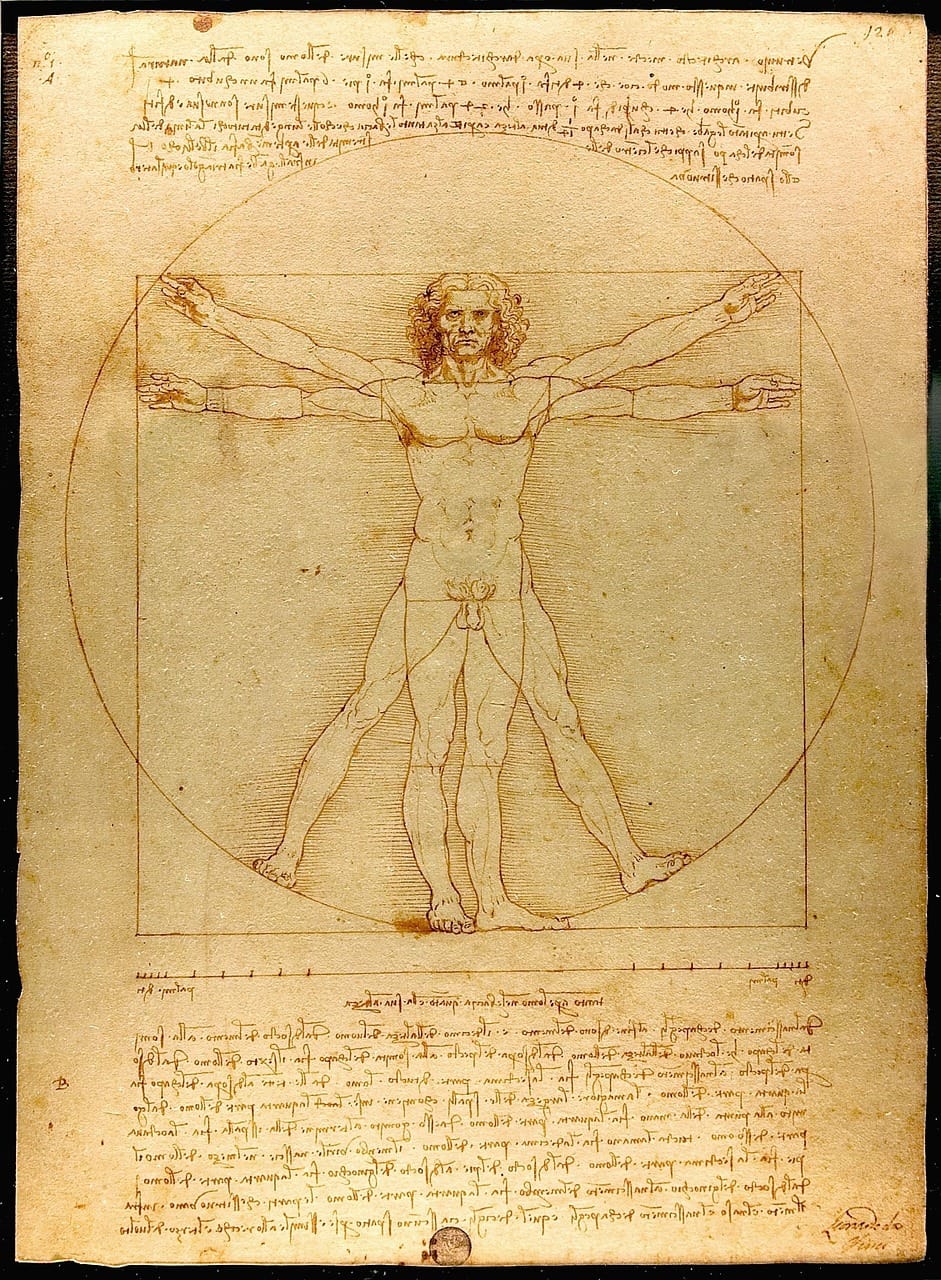

Modern medical imaging accomplishes what began in the eigteenth century as a desire and a search for illuminating every dark corner, especially for seeing the insides of the human body. Modern man has since been rendered somatically transparent, in gestures that extend into putting on full view not only the hidden but the ultimate microscopical—the DNA fingerprinting, the biochemical profiles, the immune cellular probes and markers.

Our times have renewed the visible and the explicit as a preeminent presence, compared with times when the rarefied world of pure ideas and Logos was supreme and the image mere appearance. Increasingly, we communicate with images of people, with virtual persons existing as bytes in optical fiber ready for multiple displays. The radiologist looks at his echography machine, not at me. The image becomes the inevitable mediator between my lived intimacy and the dispersed network of the expert medical team for which the images are destined. I am disseminated in image fragments that count more as the relevant interface than this presence (my lived body then, but again the question of which one?). The image holds the bond at just the right distance: sufficiently close so as to be a habitual part of my intimacy, sufficiently detachable so as to introduce a wide space wherein the intrusion of otherness arrives massively every time I go back to the stretcher and raise my shirt and the probe glides over my abdomen. (In these situations, habit has transformed them almost into a self-touching—a tribute to the force of the image: I can feel those black and white patterns on the screen.)

Occasionally, in one of the check-up visits the clinician asks me to lie down and he touches my liver region. I experience it as a relief, as return to an embodied presence. The touch reestablishes an older intimacy through his touching hand. Touching/being-touched is the paradigm of oneness, me-ness. These gestures are always considered supplementary: only the images and the charts speak the reliable truth, having captured the essence of the story. These body-techniques seem to stand for all that was tactile, tangible and ready-to-hand, now transformed into weightless apparitions. The new body is constantly on the verge of losing its seemingly invincible spatial and temporal structure.

It would be idle to set up an opposition of correct/incorrect between these pervasive images and the contrasting sense of touch, anchored in the lived body. Even in touching, the otherness is constitutive; the image rides on this doubling as a thorough mediation. We witness a push and counter-pull between depth and imaginary surfaces that become a new identity in post-transplantation life.

Intimate Distance

The encounter with the radical alteration of death approached closely over the years, and then finally made its irruption in all the brutality of a night when my chest and abdomen were laid open. It was done; I was not there, drowned in anesthetics (which “I”?; certainly there was presence, I suffered).

The descent was slow. First, waiting in a room; then getting undressed and covered with a hospital gown; then naked under a sheet so that the nurse could shave me entirely in a form of nudity that seemed to reach me under the skin. Then transferred to a wheeling stretcher, parked in the surgical room, shaking from cold and fear as nurses made conversation. The anesthesiologist comes, takes the perfusion tube and perfunctorily injects the first wave of anesthetic. I have a minute or so to let anything that was left of me go as if in an involuntary flight. Never have I felt more acutely my fragile ontology, the impossibility of grasping onto anything, a living dot suspended in a space that goes so beyond anything representable. The utter loneliness for which there is no utterance. Deprived of any intimacy, nothing left but gaping gap for intrusion. Then they open me up, cut the circulation, replace it by machines, take the organ from an ice pack, and proceed to rebuild me again back into a normal body. Or that is what they say.

Awakening into my new state, I see that the night when death traveled through my open body is to remain indelibly. It is there each time somebody looks at my torso, and I see their eyes darting quickly down to check the trace that crosses from side to side and up the chest with suture point (with big stitches, like a sack of merchandise). It’s death’s trace, which never lets me slip by this memory that is not a memory, but rather a feeling of recognition of its presence, of an inevitable guest whose movements are way beyond anything within my reach. From then on the trace of death has set its own agenda, its own rhythm to my life. I have, in fact, become another, never entirely re-done after being so meticulously undone.

Which Life?

The life retaken, is taken differently, forever changed (but to whom shall we attribute this change?) by a triple movement: the one that led to being on the waiting list; the one that led to an organ to be transferred; and the one that leads me into my present condition. This is the living reality of transplantation—my entire identity grazed profoundly by the opening to death, sutured back and left to function in the world with a “new” life. Soon the traces of the last movement begin to enter my life as multiple foreignness.

There are first and foremost the drug treatments, which are prescribed in quantities and taken by grams per day, and that mark the temporality of the day, of travel always present in its medicine bags, bulky and obtrusive. Then the drugs themselves. The cortisone and immunosuppressors, which induce a diabetes that needs careful checking three or four times a day. The effect on the stomach, producing sometimes uncontrollable diarrhea that in all its undignified presence overtakes my life. And of course the repetitive medical controls: the enzyme levels to keep track of, the overload of the kidneys to verify. The Hepatitis C virus is, we all knew it, still with me, and we know it to be back in full action, the most mysterious of my foreignness, degrading the new liver. It must also be suppressed and controlled. It is an imaginary circle: I am back where I started from, intertwined with these amazing dots whose molecular structures I sometimes contemplate in awe of their twisted proteins and minute RNA. But the only known antiviral treatment is interferon, an immunitary stimulant, which produces a permanent feeling of fatigue as if one has a budding cold. In fact, for effectiveness it must be taken with ribavirine, which leads to anemia. Oddly, the immunosupression to avoid rejection is exactly a counter move to interferon, so that the body is pushed on opposite sides at the same time. (A constant paradox: immunosuppressed to avoid rejection; immunostimulated to avoid the virus. A telling symbol of my condition.) There is also the return to the hospital for a sudden explosion of viral activity, for the accumulation of liquid around the liver that needs extensive examinations.

Changing symptoms that emerge and subside: echographies, weight control, blood samples so often that my veins seem to expect the needles. Thus the foreignness of the grafted liver is less and less focused. The body itself has become a constant, ongoing source of foreignness, altering itself as in echo, touching every sphere of my waking life. This is the life that I have survived for, not a coming back to where I was (but I was already alienated by the disease for long years, and before seems distant and abstract). A life with its own temporality to put together and to live with the multiple manipulation that technology demands (once again the historical contingency of the body-technologies: in ten years more I would have been some other kind of survivor). Compensation to the decompensations that multiply in a hall of mirrors. The suffering varies from one person to the next in its extremes. The phenomenon rests: transplantation has made the body a fertile ground of opposed, coincidental intrusions.

Inconclusion

Transplantation produces an inflexion in life that keeps an open reminder from the trace of the scar altering my settledness, bringing up death’s trace. It is my horizon, an existential space where I adapt slowly, this time as the guest of that which I did not arrange, like a guest of nobody’s creation. This time, the foreign has made me the guest, the alteration has given me back a belonging I did not remember. The transplant ex-poses me, ex-ports me in a new totality. The expression of it all, I know, eludes me, makes me face a twilight language.

Perhaps we are all (the growing numbers who have entered into the sphere of this transference) “the beginning of a mutation,” as Jean-Luc Nancy says. I can see it: all of us in a near future being described as the early stages of a mankind where otherness and intimacy have been expanded to the point of recursive interpenetration. Where the body altered technically will and can redesign the boundaries ever more rapidly, toward a human being which will “intrude into the world as well as into itself.” We would do well to consider this.

It is this urgency that drives this examination of the ancient ethos of the human will to power re-expressed as transplantation, even if my own window on it is narrow in time and fragmented in understanding. Somewhere we need to give death back its rights. ©

This is an adaptation of Intimate Distances: Fragments for a Phenomenology of Organ Transplantation, by Franisco J. Varela, which first appeared in the Journal of Consciousness Studies. © 2001 Journal of Consciousness Studies.