Melvin McLeod: Over the years, you’ve made passing references to Buddhism, but this is the first time you’ve discussed your Buddhist practice in detail. How long have you been a Buddhist?

k.d. lang: From a very early age I have considered myself to be a Buddhist. I don’t even know where that came from, it was just an innate feeling. I was also very interested in—and very sure of—the concept of reincarnation. Then the older I got and the more I learned about Buddhism, the more I felt at home with its principles and philosophy. I took refuge as a Buddhist about seven years ago, so it’s clearly something that I’ve kept relatively low key in the press. I don’t think it’s necessary or even helpful to advertise your practice of the dharma.

Melvin McLeod: What type of Buddhism do you practice?

k.d.lang: About eight years ago I met a teacher here in Los Angeles from the Nyingma lineage of Tibet, Lama Chödak Gyatso Nubpa. The great teacher Chagdud Tulku asked him to come here and work on stabilizing dharma in the West. Lama Gyatso quickly became my teacher. I have been practicing and studying with him since.

I’m very proud to be a Nyingma practitioner. It totally suits my character. It’s the oldest Tibetan lineage and yet in some ways the most radical, you might say. Although there is plenty of academic study, it is not fundamentally academic. Beyond that, the importance of being a Nyingma to me is the purity of the lineage. The oral transmission has remained unbroken and it’s very, very potent. There is an unwavering dedication and homage to Guru Rinpoche, the founder of the lineage, and to your root lama. That kind of deep dedication is what makes the Nyingma tradition so special.

Melvin McLeod: What practices do you do?

k.d. lang: I’m actually in the middle of doing my ngöndro, the preliminary Vajrayana practices. I practice it in my hotel room, on the plane, wherever I can. As far as our sangha is concerned, there are practices that we do as a group on a regular basis. We have a thröma retreat that we do every year. We do Yeshe Tsogyal and a few other secret practices. We do Orgyen Dzambhala every New Year’s.

Melvin McLeod: Committing to a teacher as you have, particularly one in the Tibetan tradition, can really turn your life upside down.

k.d. lang: Yes, absolutely! [Laughs] That’s very true! When you find your teacher your life is turned upside down, but in the most divine way. My involvement with the dharma has completely changed the structure of my life. Our sangha is very small, so we work very hard. I would say that supporting Lama Gyatso Rinpoche’s activities is my number-one job. Together with my partner, Jamie Price, I’m on the board of directors of Ari Bödh, the American Foundation for Tibetan Cultural Preservation. We’ve been building a long-term retreat centre on a 475-acre retreat property north of Los Angeles. We’re just four years old now, but we are planning to create a facility that will accommodate retreats of three or more years. We have a temple, which has a lovely statue of Guru Rinpoche commissioned by Lama Gyatso.

We also have a children’s camp called Tools for Peace. The curriculum we use there is being translated into four languages now. Kids come to Ari Bödh every summer for the camp, and I serve as a cook and bottle washer there. It’s very rewarding.

Melvin McLeod: What about your singing career?

k.d. lang: Well, my singing career got put on the back burner a little bit. When I took refuge and became a practitioner in earnest, I started devoting my time and energy to practice and building our meditation center. Music became this thing that basically kept me paying the bills. Fortunately, I had the opportunity to make the record with Tony Bennett, Wonderful World, and then Hymn to the 49th Parallel, an album of covers of classic Canadian songs. Interpretive records take far less time and energy than writing and recording your own record.

Also, starting on the path really wreaked havoc on the concept of writing material. I was always worried about whether I had to literally become like Milarepa, the great yogi and ascetic, and write songs about spinning the dharma wheel [laughs]. I was a little nervous about the prospect of having to do that. That was one of the reasons it took me so long to write the new record. I was processing all of this information I had been learning and absorbing, which was changing the actual structure of my brain, and my soul, and my heart.

Melvin McLeod: It’s not unusual-I know myself-to think at the beginning that you have to go off and live in a cave or something.

k.d. lang: Exactly. You can become pretty carried away, to the point where you feel you have to let go of your friends and your house and all sorts of things, and nothing can be integrated. It’s total chaos. Then all of a sudden everything starts to integrate. At a certain point, Buddhist practice is so inseparable from everything you do that you start to live and breathe it. I suppose that’s the gradual process of awakening-it’s naturally incorporated into your very being. You don’t even think that you’re processing things in a “Buddhist way,” particularly.

Melvin McLeod: What about your songs?

k.d. lang: I had a couple of conversations with Rinpoche, asking him whether it was important for me to actually integrate my practice into my lyrics. He told me, “Oh, no. Not necessary.” That was a big relief, because it took away the pressure of having to produce explicit dharma songs. Of course, the dharma is integrated into the way I think and breathe and live, so it’s also integrated into the way I write lyrics. But it hasn’t been purposeful. It’s been natural. It has been a total relief to realize that. Buddhism is a religion of non-proselytizing, so it would have felt very unnatural to make an effort to include Buddhism in my lyrics.

Melvin McLeod: How would you say, then, that your practice has affected the songs on your new album?

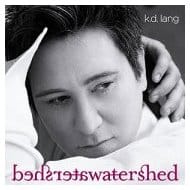

k.d. lang: I’m a young practitioner. I’m really just in the initiation stages, which is like standing naked in front of the mirror and diving inside to see what you’re working with, what kind of a mess is going on in there! [Laughs] The new album, Watershed, is a reflection on my various relationships-my relationship to my partner, my relationship to my music, to my fame, to my teacher, to this existence. I try and touch on those things on some of the songs, such as “Je Fais La Planche” and “Flame of the Uninspired.” “Coming Home” is about finding my past. I tried to write the song in a way that would transcend all of the pedantic ways of expressing it, and just be completely naïve about it, you might say.

Melvin McLeod: I have always been struck by your willingness to expose yourself in your music-your heart, your desires, your pain. That kind of openness and vulnerability, which takes courage, is a core dharma principle.

k.d. lang: I guess that’s been there. I would like to think I’ve always been Buddhist; it just took me a while to find my teacher.

Melvin McLeod: Your song “Constant Craving” is a beautiful and accurate restatement of Buddhism’s first noble truth.

k.d. lang: I think “Constant Craving” just comes out of the experience of being human. The realm of desire is such a common theme in my music. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s because I like it so much. [Laughs]

Melvin McLeod: My Buddhist teacher, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, said it was essential for the Buddhist practitioner to have a “sad and tender heart.” Your music often has those qualities of tenderness and pain.

k.d. lang: Definitely. I suppose “melancholy” is a word that might apply, but I kind of shy away from that word because it carries a negative connotation. There is, though, a peacefulness in melancholy, because it’s balanced. When something is too entirely desperate, or too entirely sublime, it’s not balanced. The middle way is the most sustaining.

Melvin McLeod: Does the title of the album, Watershed, refer to your own life and what you’ve gone through becoming a committed Buddhist?

k.d. lang: I would say so. The idea of watershed has a great deal of pertinence to becoming a Buddhist and following the path. It seems to me that the flow of dharma-or the flow of one’s own innate buddhanature-is like water. There are obstacles, but eventually the water will find its way around them. A change of direction happens when you take refuge and become a practitioner. For me, it’s been about reassessing, reviewing, and reprioritizing everything in my life. It’s been about revitalizing my morality and my relationship to cause and effect, meaning what I do as a person-with my body, speech, and mind-and how it affects all other beings. Each song, as I said, is about my relationship to something, and it’s also about the cause and effect of each of those relationships.

Melvin McLeod: When the album comes out, and you talk to the mainstream press about the title, are you going to talk about it in Buddhist terms, as you are now?

k.d. lang: I would essentially answer in the same way I’m answering you, although I wouldn’t use terms like “bodhichitta” or “planting the seed of dharma” or “refuge” because dharma is a very personal thing and I wouldn’t want to have it taken out of context, which I think would be a negative thing.

Melvin McLeod: In other words, it’s better to be it than preach it.

k.d. lang: Exactly. I think we’ve seen instances where famous people have talked about Buddhism in the press, in a way that was not necessarily beneficial. I feel very protective of the dharma path and very protective of my relationship with Rinpoche. But at the same time, I want to connect people to it, I want to awaken people to it. I have been very cautious, though.

Melvin McLeod: Beyond its impact on your lyrics, has your meditation practice influenced how you sing?

k.d. lang: Absolutely. The effect on my voice is immeasurable. Truly immeasurable. Doing mantra and doing the prayers has completely changed my voice. Once again, I don’t know if I can define it exactly. It’s more ethereal or elusive than saying something like, “My voice is enriched by the lower register.” It’s not that simple. My relationship to the control and fear of singing is gone. I don’t mean breath control. I mean control as in forcing myself into the music and feeling that I’m controlling the music, rather than feeling like a vessel or a vehicle. I trust my teacher so much, and I trust the path so much, that I also trust that I can do the work and simply be a vessel for something larger.

Just to know that there’s a greater purpose to my music, a real purpose, has taken all the work out of it. That’s emancipating, because I don’t get stressed singing anymore. I don’t get tired singing anymore. The very first thing Rinpoche said to me the first time I met him was, “Make sure your motivation is clear.” I’d always thought that my motivation was right, but it turns out that there’s a lifetime of examination in finding true motivation.

Melvin McLeod: How do you feel your music can benefit others?

k.d. lang: The most important thing about my music-other than making people happy and peaceful for a second-would be the good fortune I have to be close to the lineage masters. Somehow, through my music, I could connect the listeners to those masters.

Melvin McLeod: The blessing of your connection could come through the art you produce.

k.d. lang: Yes. Certainly not in a mundane, phenomenal way, but in the most divine way possible.

Melvin McLeod: Many musicians try to communicate emotion through elaborate ornamentation. Your music tends to be spare and straightforward, and yet to me it conveys more emotion and meaning. Is that quality of space and simplicity something you have consciously cultivated?

k.d. lang: I could go on about this topic for hours. There are many reasons for that kind of quality in the music I do. Number one, I am a Buddhist, so emptiness is everything. When people ask, “Do you look at the glass as half full or half empty?” I always say, “I’m Buddhist. I look at it as half empty!” [Laughs]

To me, space is everything. Space is the opposite truth to sound, so it is as important as sound. As a producer, I’m always looking for space, and I’m always looking to create that pocket, especially for the voice.

I grew up in the Canadian Prairies, so I know about big spaces. I think my basic aesthetic, as a person as well as an artist, is minimalist, because of the Prairies. Ornamentation, I think, is an urban aesthetic. I would venture to say that it is an African-American urban sort of thing. I think it stemmed from the gospel. That is not my background, who I am, my history. When you hear Mahalia Jackson or early Stevie Wonder or early Aretha Franklin, or early gospel singers, that’s a very pure, beautiful thing. It’s real. Now, music with a lot of ornamentation is often a caricature of that pure form. It’s fraudulent.

Melvin McLeod: Speaking as a fan, which I have been for many years, I would say that you have one of the finest voices in the world, like a Maria Callas, Pavarotti, or Streisand. If it’s not too strange to ask, what is it like being able to sing like that?

k.d. lang: On a purely mundane level, it is totally mind-blowing to have this sound come out of my body. It feels like a whole ocean of surfers are available to me at any given moment to open up my voice and play around with a melody. It does blow my mind.

But the deeper truth is that we all have world-level gifts. I’m not just saying that. I honestly believe it. Maybe sometimes we are not able to reach and bring out our gifts, but they are there. It can be quite ordinary-when you see a Bhutanese woman making cheese dumplings and you taste one and it’s the best cheese dumpling you’ve ever eaten in your life, it’s the same thing! It’s essence. Ultimately, I don’t really see myself as separate from anybody else in terms of having a gift.