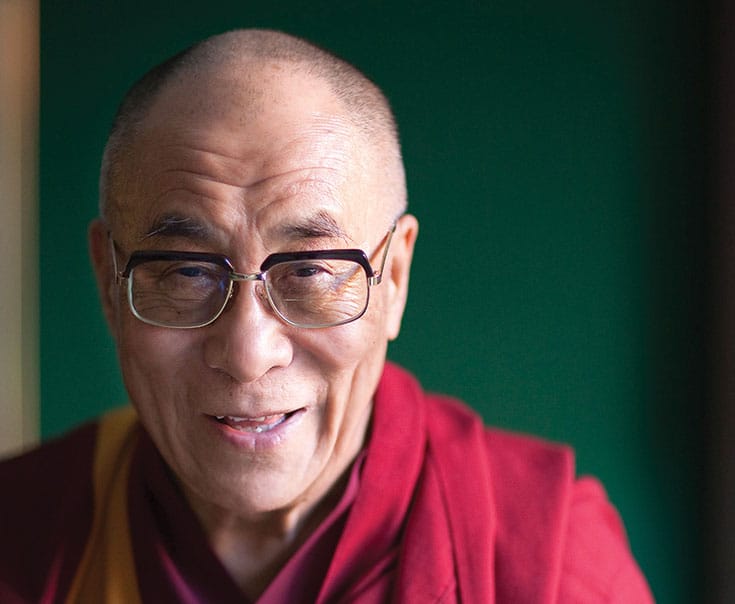

The Dalai Lama draws lessons for all of us from his own experience dealing with difficult times. From a conversation with Mary Robinson, former prime minister of Ireland and U.N. high commissioner for human rights, moderated by Pico Iyer and presented by the Tibet Fund.

Pico Iyer: Your Holiness, many people in the United States are suffering because of the recent economic downturn. You’ve seen so much loss in your life and yet you remain so confident. How do the rest of us find confidence when our lives are unraveling?

The Dalai Lama: Yes, this is quite serious and very sad. I feel that those people who just think about money, people whose whole hope is based on money, have found this global economic crisis much more of a disturbance than others have. Then there are people with different values. Yes, money is important to them—after all, without work, without money you can’t survive. But for people who are full of love and compassion, whose values are based on family, neighbors, community, I think they’re much happier, even though they’re having the same difficult experiences.

I think it’s good to be reminded that there are limitations. Many years ago, when the Japanese economy was growing very rapidly, I said during a visit there that it might not always be like that. When the Japanese economy started to have problems, some economists and businessmen there said they appreciated my view.

The present crisis in the world economy is the result of too much greed, speculation, hypocrisy, and lies. But if we are honest and realistic, then these kinds of things might not happen.

Mary Robinson: Given that we’ve had this crisis because of, as you said, greed and hypocrisy, how do we get to a more ethical, fairer globalization?

The Dalai Lama: First, there’s a gap: the rich and poor. This is very serious on both a national and global level. Even in the United States there are still pockets of very poor people while the lifestyle of the richer people is luxurious. That is not only morally wrong but a source of problems. The poorer people always feel frustration. The frustration transforms into anger. Anger transforms into violence. We have to think seriously about how to reduce this. I think the immediate possibility for the poor is to get them skills through education, and most important, give them self-confidence.

The reality of our planet now is that every nation is interdependent, interconnected. So, the concept of “we” and” they” is no longer valid. The entire world should be part of “we.” One’s own future entirely depends on the rest of the world. Yes, the United States is the biggest nation, the most powerful economically, but your future depends on the rest of the world. That’s the reality. So treat others as a part of yourself. We need a concept of oneness, of humanity. We need a sense of global responsibility.

Mary Robinson: I’m very pleased about a new kind of women’s leadership that is connecting women who have access to power and influence with women who are suffering in poverty in places like Darfur and Chad. This is exactly what you’ve recommended—developing connection, empathy, and compassion, and using leadership to change people’s lives.

The Dalai Lama: The time has come to emphasize the importance of loving-kindness, affection, compassion, and wholeheartedness, rather than simply education. I think, generally speaking, women have more potential for this. So women should take a more active role. I truly feel that we might be safer if more women were the leaders of this planet.

Pico Iyer: Your Holiness, when you arrived in India in 1959 after the Chinese invasion, knowing you had to reconstruct Tibetan culture in exile, what were your priorities and inspirations?

The Dalai Lama: When the 1959 crisis happened in Tibet, I did my best to cool down the situation, but I failed. Once in exile, the immediate task was to look after the several thousand Tibetan refugees who had followed me. Then the longer-term challenge was to preserve Tibetan culture, and at the same time to promote modern education among our people.

At that time, our slogan was “Hope for the best, but prepare for the worst.” We hoped that within one or two years we would be able to return to Tibet or find some other solution. Now, fifty years later, I still don’t know how long it will take. But we had always prepared for that possibility, and when I look back, all our major decisions seem correct. When we planned our struggle, we planned for the worst. We knew it could take generations, so we planned accordingly.

I think we have one of the most successful refugee communities. The preservation of our culture and heritage has been quite successful. Today, many people come to India from Tibet to get Buddhist teachings and modern education. We feel quite proud of that.

Mary Robinson: I don’t think I’ve ever told Your Holiness how difficult it was when I was invited by China to visit on the fiftieth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in 1998. I was U.N. high commissioner for human rights at the time and I told them that if I went, I wanted to go to Tibet. They said no, but after many discussions I got permission.

It was an extraordinarily special visit for me. One thing I recall vividly was going to a school in Lhasa. I had little copies of the Universal Declaration in the Tibetan language, and we gave them to the teachers. They had never heard of the Universal Declaration of Human Right, and I was very happy to give them out so the teachers could use them. One of my human rights officers whispered to me that this was probably against Chinese law. But I was the high commissioner for human rights, so I said that I didn’t mind. (Laughter)

I went back in China on a number of occasions. Although I never was able to get back to Tibet, it was always an issue I raised with the Chinese Government. It’s unacceptable that the human rights situation in Tibet has been continuing and has not been effectively addressed. It’s heartbreaking from a human rights point of view.