Elijah Ary seemed like a typical Canadian kid. He lived in Montreal with his mom and dad and two sisters, he loved playing hockey, and he didn’t like school. But something set him apart: according to the Dalai Lama, he was the reincarnation of a Tibetan Buddhist master.

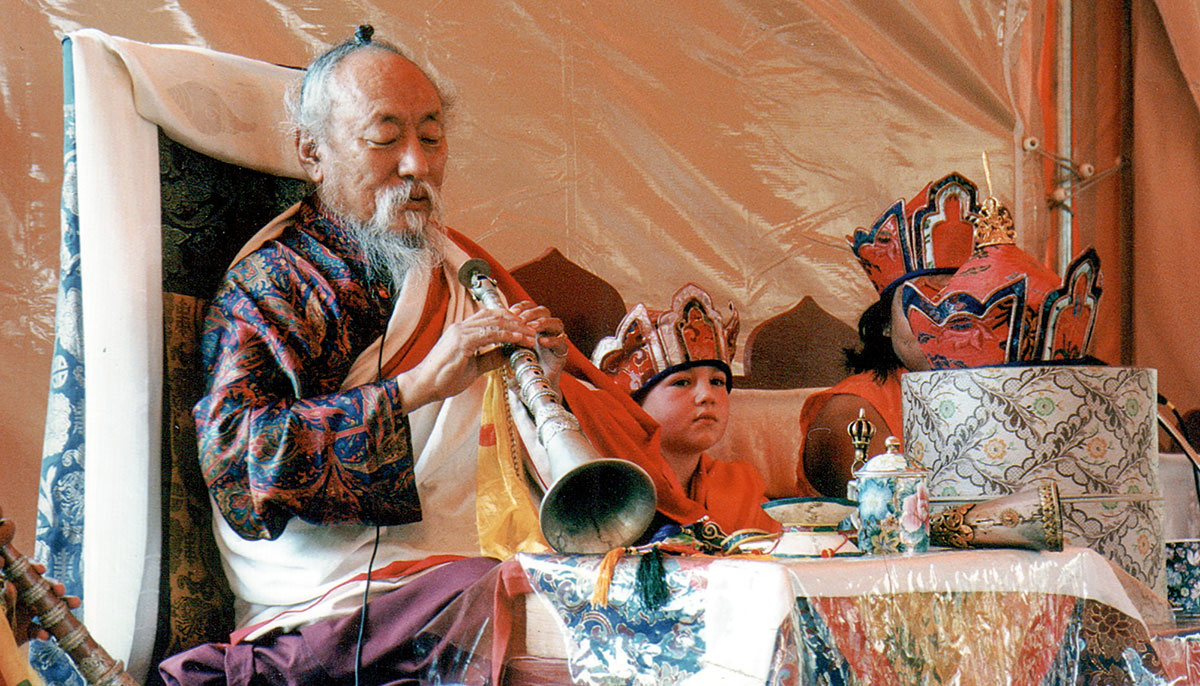

When Elijah was a child, his parents ran a meditation center, and renowned Buddhist teachers and scholars often visited the family home. Elijah didn’t take much interest until, one day, a new visitor came: a monk named Khensur Pema Gyaltsen.

Almost immediately, four-year-old Elijah began talking about people he said he used to know—people with Tibetan names—and he described a house in the mountains that belonged to one of them and the yellow bears that lived in the area.

If my existence has meaning, it’s because I’m doing good in this world. I don’t have to be a tulku in order to do that.” —Elijah Ary

Elijah’s parents were charmed by their son’s imagination, but for Pema Gyaltsen, Elijah wasn’t being cute or creative. “I know these people he’s talking about,” the khensur exclaimed.

Pema Gyaltsen investigated the boy’s past life, and eventually it was determined he’d been Geshe Jatse, a monk who’d died in the 1950s. Soon a letter arrived from a monastery in India. Addressed to Elijah’s parents, the gist of it was: You have our teacher. Please return him as soon as possible.

Elijah, now age forty-eight, is one of the handful of Westerners who in childhood were recognized as tulkus. Literally meaning “magically emanated body,” a tulku is a person—almost invariably male—who’s said to have been a realized Tibetan teacher in a past life.

In virtually all cases, those who are recognized as tulkus are of Tibetan heritage. But there are exceptions, including the three Westerners—all now adults—who talked with me about the unique turn their life took when they were recognized as tulkus. Their experience has not always been easy, let alone magical.

The tulku system, which emerged in Tibet around the twelfth century, is based on the belief that bodhisattvas are reborn again and again to help sentient beings, and that their reincarnations can be identified. While the most high-profile tulku lineages are those of the Dalai Lama and the Karmapa, there are many others.

Buddhist scholar Amelia Hall notes that the enthroning of foreign tulkus could be motivated by political needs as Tibetan Buddhism becomes international, but adds, “Who knows where the ordinary and the extraordinary converge?” As she puts it, when she takes off her academic hat and puts on her practitioner hat, she thinks, “Tulkus appearing in the West? Of course! They’re here to help.”

But while Tibetan parents might consider it an honor to send their tulku child to be trained in a faraway monastery, as far as Elijah’s parents were concerned, there was no way they were going to send their son to live with people they didn’t even know. And yet, as time went on, it became clear to them that Western life wasn’t working for him.

In third grade, Elijah and his classmates had to draw their favorite place and tell the others about their picture. Elijah, who drew the Potala Palace, said he loved it because that’s where the Dalai Lamas lived. “Have you ever been there?” his classmates asked. “Not in this life,” he answered.

He felt different from other kids and didn’t do well in school. This situation only got worse when his parents split up. “The whole thing was heartbreaking,” his father Isaac says, getting choked up. “I knew that if Elijah was going to make any progress in life, it had to be as a tulku.”

Finally, at fourteen, Elijah moved to Sera Monastery in southern India. Spending time at dharma centers in the West had not prepared him for this. “Tibetan Buddhist monasteries are a completely different culture,” he says. “So it was at once weird, but familiar. I adapted quickly. My mother said it was like watching a fish go back to water.”

Elijah, who had never been interested in school, was suddenly on the road to becoming a scholar. “I had wonderful teachers and great friends,” he says. “Studying the dharma in that context was eye-opening. It became less of a faith-based thing and more practical, more philosophical.”

For him, it was a breath of fresh air to be among people who recognized the tulku part of his identity. But life at the monastery had its challenges. As a Westerner, Elijah struggled to understand the subtleties of Tibetan culture—the unspoken assumptions and expectations. Eventually, the cultural differences took their toll, and Elijah no longer felt welcome. “There were tensions with my caretakers to the point where I was locked out of most of the rooms in my own house,” he explains. “I was told that I should leave.”

Before returning to Canada, Elijah went to Dharamsala to ask the Dalai Lama what his next step should be. “Learn psychology,” the Dalai Lama counselled, “because that way you’ll be of great benefit to many beings.”

Elijah agreed to this plan. The admissions departments at Canadian universities did not. Elijah had a shaky grade six education and none of the prerequisites. “Psychology was out of the picture,” he recalls, “but the religious studies department said, ‘We’ll have him.’”

Elijah went on to earn his PhD from Harvard University, and a version of his dissertation was released by Wisdom Publications as Authorized Lives: Biography and Early Formation of Geluk Identity. For ten years, he worked as a professor of Buddhism and Tibetan religious history in Paris.

In 1996, Elijah married his childhood sweetheart. Fifteen years later, his mother-in-law passed away, and this shook him greatly. “The big question was, if I died in a month, would I be able to say I’m satisfied with what I’ve done with my life? The answer was no,” he says. “Immediately what came back to me was His Holiness’s advice to study psychology.”

Today, Elijah is an integrative gestalt therapist, a form of therapy that dovetails with his Buddhist path. Considering his own past, Elijah says he’d have reservations if his son, now age five, were to be recognized as a tulku. “I know the downside,” he says. But, “if he were recognized, and if we chose to give him the education that I actually feel a lot of tulkus need, then we would move there as a family.”

Does Elijah really believe that he was a Tibetan monk in a past life? He admits that he used to wonder if it was all just an elaborate Truman Show–like hoax. But there are, he thinks, “a truckload” of parallels between his life and his predecessor’s and they all point to him really being a tulku.

“If someone comes along with another explanation and that stands up, then I’m fine with it,” Elijah says. “I don’t have to be a reincarnation. It’s not the most important thing. If my existence has meaning, it’s because I’m doing good in this world—I’m helping people. I don’t have to be a tulku in order to do that.”

“I’m a very liberal, free guy. I don’t like rules,” says Spanish-born tulku Tenzin Ösel Hita. “I think my purpose mainly is to break people’s expectations and idealizations and maybe even a little tradition.”

Following suit with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Ösel believes that the real point of the tulku system is preserving and sharing the buddhadharma. “The dharma can help you understand your own nature and connect with that and improve your life. So that is very special,” Ösel says. “That has to be kept pure without all these other contraptions and conceptions that people come up with.”

Ösel is at once free-spirited and utterly devoted to the dharma, and shares these qualities with the teacher he’s said to be a rebirth of—the dynamic and unconventional Lama Thubten Yeshe.

Lama Yeshe used to joke he was a Tibetan hippie who’d dropped out. In his famed courses at Kopan Monastery outside Kathmandu and through his Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Lama Yeshe and his student Lama Zopa taught Buddhism to thousands of Westerners. When he died in 1984, his Western students immediately began longing for his return.

A year later, Ösel was born to María Torres and Francisco Hita, Spanish students of Lama Yeshe. Ösel was an unusually calm, contemplative baby, and people felt he had mannerisms similar to those of Lama Yeshe. Lama Zopa, who was trying to determine the location of his guru’s incarnation, was investigating Ösel and various other children.

There were signs that indicated Ösel, and Lama Zopa decided it was time for the traditional test. So he laid out some of Lama Yeshe’s former possessions along with other similar items and asked Ösel to choose the things that were Lama Yeshe’s. Ösel, still a toddler, reached for Lama Yeshe’s beads and bell.

Decked out in robes and a yellow hat, the child was enthroned as a tulku. One reason the ceremony was so special for him was that it was the only time he remembers seeing his parents together. They separated, and in any case he lived on his own, far away from them.

First, he resided at monasteries in Nepal and Switzerland. Then at age seven, he moved to Sera Monastery, which, he says, was very isolated at that time. “Maybe we had three hours of electricity during the day, and during the night we had candles. They would bring milk in a jar. It was still warm, and we had to boil it. There was no telephone, no internet, no TV. Maybe somebody had a radio.”

Ösel managed to enjoy his free time, playing on the swings behind his house and reading fantasy books about dragons. Yet the strict monastic training was not easy.

I think my purpose mainly is to break people’s expectations.” —Tenzin Ösel Hita

Tutors and caretakes would come and go. One teacher was the only constant presence in Ösel’s life, and they spent an hour or two together daily. “My teacher was like a father, like a mother,” he says, “so kind, compassionate. He taught me many things, most of all through his example.”

Being at the monastery, Ösel says, “was a privilege, a gift. I’m so grateful I had that opportunity.” At the same time, he explains, he was deeply curious about Western culture and wanted to figure out who he was outside of his monastic bubble. What would it be like, he wondered, to interact with people who didn’t think of him as a tulku or teacher?

At age eighteen, Ösel left the monastery. First, he went to Canada, where he earned a high school diploma. From there, he went to Switzerland to study liberal arts. But itching for more freedom and fewer rules, he took off after six months and threw himself into a freewheeling adventure in Italy. For a time, he lived on the streets of Naples and Venice.

From 2006 to 2008, Ösel apprenticed in Bologna under Emmy Award–winning filmmaker Matteo Passigato, and in 2012 his first short film was released. Called Being Your True Nature, it’s a documentary about Lama Yeshe’s methods for helping modern people access ancient psychological tools in order to lead happier, more meaningful lives.

As a student, Ösel never told anybody he was a tulku. If pressed for information about his background, he’d just say his parents were Buddhist hippies and he’d grown up in India. “For me, it’s been very important to meet people, and for people to meet me, without all of that,” he says.

Nonetheless, Ösel is sometimes put on a tulku pedestal. When this happens, he manifests that aspect of himself for the other person’s benefit, but as soon as the opportunity arises he gently dismantles their projections. “We don’t need all those complications,” he says. “We’re all humans. We’re all struggling. We’re all learning from each other.”

From 2008 to 2013, Ösel was on the board of directors of the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition. Since 2010, he’s given dharma talks at their centers in Europe, the U.S., and Brazil, and now he’s codirector of Tushita Meditation Center Spain. On the FPMT website, this quote from Ösel is prominently displayed: “There is no separation between me and FPMT. … We are all working together in so many aspects and terrains. Humanity is our office.”

In 2015, Ösel was leading a pilgrimage in India and Nepal when a devastating earthquake hit. In response, he cofounded the charitable project Revive Nepal. More recently, he spearheaded the Global Tree Initiative to bring people together to slow global heating by planting trees. Today, he lives in Valencia, Spain, where he amicably shares custody of his three-year-old son Tenzin Norbu.

“I’m so privileged to be able to spend time with my son anytime,” Ösel says, “and for him to be able to have both of his parents together in harmony, something that I, as a child, was never able to experience.”

“Tibetan culture is part of my culture,” says Ösel. “So that’s what I offer Norbu. I speak to him in Tibetan, and when he gets to a certain age, I will take him to Dharamsala to study with Tibetan children. We’ll spend time in the monastery because I always go back to spend time with the monks.”

Tulku Bino Naksang, who is of Tibetan heritage, comments on Tibetan Buddhist teachers recognizing Westerners as tulkus. “It was a failed experiment,” he says bluntly.

The reason it didn’t work, he asserts, is because even when Western tulkus were given a monastic education, over time their Western culture would manifest in them and they’d start to see faults with the monastic institution. “They lean toward the Western ideology of human rights and freedom of speech,” he says. And this would create conflict.

But, Tulku Bino adds, it’s not just Western tulkus who are influenced by Western ideas and ultimately give up their robes. “This also happens to Tibetan tulkus.”

Some Tibetan tulkus who leave the monastery are so unprepared for lay life that they fall into substance abuse. Others build more satisfying lives. For example, says Tulku Bino, “Yesterday, I was talking to one of my tulku friends who is in New York, happily driving for Uber.”

As for Tulku Bino himself, he was always told by his teacher that he had to study for the sake of all sentient beings. “I used to think, why do I have to care about sentient beings? What about me? As a young child, having to liberate all sentient beings was a huge burden,” he says. “I started rebelling against it, and I did everything opposite to the way they wanted.”

After Tulku Bino walked away from the tulku life, he moved to the U.S., where he now resides with his wife, Buddhist scholar Amelia Hall, and their thirteen-year-old daughter.

“What I renounced is the complication of the institutionalized tulku system,” he explains. That said, “I am a reincarnation. I am a 100 percent sure about that. The problem is how the system has evolved. It is overtaking the real purpose of the dharma itself. So, ultimately, I think the system will dissolve. His Holiness says he might be the last Dalai Lama, but that does not mean he’s not going to reincarnate again. What he’s saying is the system might completely dissolve.”

In Tibetan society, the tulku system has spiritual and practical functions that are so entwined they’re difficult to separate. The tulku system is what keeps the monasteries running from one generation to the next. As lineage holders, tulkus are trained by their predecessor’s students and they inherit their predecessor’s estate. The high-minded purpose of the tulku system is to spread the dharma and wake people up. But as Tulku Bino points out, “The intention might be to benefit sentient beings, but there’s also a tremendous amount of wealth involved.”

Some people in the Tibetan community, including the Dalai Lama, have talked about the possibility of electing leaders rather than continuing to enthrone tulkus. But not everyone is on board with that, as it’s believed that the tulku system, however imperfect it may be, has brought great benefit to Tibetan society.

As Tulku Bino sees it, the Dalai Lama is compelling proof that the tulku system can be highly effective for helping people wake up. His Holiness was a boy from a modest family in a remote corner of Tibet, and yet he came to hold the most prestigious seat in Tibet and, ultimately, to have a positive impact on the whole world.

Yet it seems that recognizing Western tulkus has not been viewed as ultimately helpful to Tibetan Buddhism, because it’s been decades since leaders have shown interest in recognizing Western children. The cause, in a nutshell, seems to be that the tulku system is not an easy fit for Western culture. The Western children who were recognized in the seventies and eighties were all born to convert-Buddhist parents who’d studied with Tibetan teachers. But even then, there was a gaping cultural divide when it came to the traditional tulku system.

“Westerners must find their own kind of Buddhism,” concludes Tulku Bino. “This tulku system is unique to Tibetans. I don’t think it will survive in another culture.”

When American tulku Wyatt Arnold is asked how he’d feel if his four-year-old son were recognized as a tulku, he doesn’t see the point in thinking about it.

“It will never happen,” Wyatt says. “Not because he’s not, or he is. It’s because that whole thing of recognizing Westerners has been exhausted. It’s like, nope, that’s not gonna work.”

Buddhism in the West lacks a strong monastic culture. As a result, Wyatt says, “You don’t have the type of environment that is required for individuals who’ve been recognized to understand what the role means or to become legitimate dharma practitioners themselves. Without that system, the recognition of a tulku has no purpose.”

Children are emotionally and educationally immature. If you give a child a lofty title, Wyatt says, “you have to have some system to create growth.” For Wyatt himself, “That was lacking.”

Born in 1987, Wyatt was recognized as a tulku by the late Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche, a Tibetan teacher in the Nyingma school who was prominent in the West. Wyatt was enthroned at age five, but his mother refused to send him to a monastery in Asia, and he grew up in Oregon, California, and Colorado.

Occasionally, one of his school teachers found out he was considered a tulku and asked him to speak to the class about it. “It wasn’t uncomfortable,” Wyatt readily admits. “I liked being the center of attention.”

Wyatt became consumed with highfalutin ideas about what it meant for him to be a tulku, and whether or not he was living up to the role. This made him act out, and in his first year of university, he partied too much. In need of a reset, he went to India to study with Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche and ended up staying for five years.

This was a transformational experience. As Wyatt puts it, he landed in India with “an immature way of thinking about things” and then learned what really matters.

Wyatt is no longer so preoccupied with being a tulku that it gets in the way of his life. Yet it has left a mark. “Some of my habits are still driven by that label,” he says. “There’s still a bit of ego—a bit of insecurity—about whether it’s been a success or not, in terms of me fully taking on that role.

“Personally, I feel successful,” he says. “I’m able to take care of myself, take care of my family. I don’t have strong resentment or regrets. I have a really close connection with the buddhadharma. So that is success—100 percent.” That said, if you define a successful tulku as being a lineage holder who understands the dharma so deeply that they can transmit it others, “I don’t have that,” he says.

Today, Wyatt is a civil engineer and is working on his master’s degree. Between his career and parenting, he’s so busy that he doesn’t have much time for meditation. “To call my practice anything more than maybe a few seconds here and there would be overselling it,” he says. His focus is on being aware of his thoughts, actions, and feelings and remembering Buddhist principles.

Wyatt used to want to be a Buddhist teacher. Now, he wouldn’t put it that way, though he very much wants to see the dharma cultivated in the West. “I think anybody who’s a Buddhist wants to do whatever they can to make that happen,” he says. “Teaching is one way, but that’s not where I am right now. My first goal wouldn’t be to teach. It would be to become an authentic general practitioner—to develop deep understanding.”

When asked if he believes he really is the incarnation of a dead lama, he says he used to. Now, he doesn’t think about it in such a binary way—yes or no, believing or not believing. “I don’t think it really matters,” he says. “What matters is that I maintain interest in understanding, practicing, and applying the teachings.”

According to Elijah Ary, the last time he had any recollection of his past life was when he and his wife visited the monastery in Tibet where his predecessor had lived. There, he met an elderly monk who was doing prostrations.

“Do you have any pictures of Geshe Jatse?” Elijah’s wife asked.

“Yes,” the monk answered, showing them one tiny shot in black and white. “Geshe Jatse was my teacher. His reincarnation lives in North America.”

“Yes, I know,” said Elijah.

“Oh, you know him?”

“A little,” Elijah quipped, but then he said, more seriously, “He’s standing right in front of you.”

The old monk burst into tears. “I was the one who was responsible for your body when you died. I never thought I’d see you again.”

From that moment on, the two shared a special bond. Elijah helped him financially and the monk sent Elijah gifts of honey and tsampa, the roasted barley flour that is a Tibetan staple. Then one sad day, money Elijah sent was returned to him. The account had closed; the old monk had died.

For some people, this is the end of the story. For others, for those who believe this sort of thing, it’s just the beginning. Eventually, in this life or the next, Elijah and the monk will be together again.