The ancient holy sites in India and throughout the Himalayan region have been blessed again and again by buddhas and bodhisattvas throughout the ages, and have been visited by millions of pilgrims; this is what makes them so vibrantly alive and profoundly affecting. These holy sites have not been organized or controlled by anyone. No one is choreographing a “holy site experience” and there’s no serious exploitation, which means that, so far, they are free from any trace of a Disneyland mentality. It’s still possible to sit by the River Ganges in the afternoon to watch the cremation ceremonies, smell burning human flesh, and be enthralled by the continuous round of Vedic chanting, as if nothing has changed for three thousand years.

Generally speaking, the environment we inhabit affects the way we think and the way we look at our surroundings. It’s worth remembering that, of all the billions of planets Shakyamuni Buddha could have been born on, he chose ours; and of the hundreds of countries that make up our world, he chose ancient India; and of all the places he could have attained enlightenment, he chose the Indian state of Bihar. At first glance, Bihar doesn’t appear to be either serene or spiritual—quite the opposite. But once you arrive at Bodhgaya, for example, and especially when you enter the inner circle, you can immediately feel that it’s really a very special place. Or Vulture’s Peak, which is so tiny that you can walk past it in ten paces and when looked at through the eyes of a real estate developer is a social desert, yet it’s where Lord Buddha gave some of his important teachings to hundreds of monks, arhats, and bodhisattvas.

Just before the Buddha passed into parinirvana, his close disciples asked him, “As Buddhists, what should we tell the world about you?” Buddha then gave them a great deal of advice, including four specific pieces of information for the benefit of his own students as well as all sentient beings.

“You must tell the world that an ordinary person, Siddhartha, came to this Earth, achieved enlightenment, taught the path to enlightenment, and didn’t become immortal but passed into parinirvana.”

To put it another way, he taught:

- Although sentient beings are defiled and therefore ordinary, we all have buddhanature;

- Our defilements are temporary rather than our ultimate nature, and are therefore removable—as a result we can become buddhas;

- There is a path that shows us how to remove our defilements and attain enlightenment; and

- By following this path we will attain liberation from all extremes.

The Buddha’s teachings offer a variety of methods to help us remember these four statements, from chanting mantras to elaborate meditation practices. Remembering these teachings and putting them into practice is the backbone of the Buddhist path, and one of the traditional methods that help us do this is the practice of pilgrimage.

Many spiritual traditions encourage their followers to go on pilgrimage. Since Shakyamuni Buddha is the supreme teacher in whom all Buddhists take refuge and whose teachings we do our best to follow, for us the most significant holy places are those where he taught and acted for the benefit of sentient beings. While we should aspire to visit all these places, traditionally four sites are considered to be the most important:

- Lumbini, where Siddhartha was born in this world as an ordinary person;

- Bodhgaya, where Siddhartha became enlightened;

- Varanasi (Benares), where he taught the path to enlightenment;

- Kushinagar, where he passed into parinirvana.

It’s important to remember, though, that the main point of pilgrimage isn’t just to visit a saint’s birthplace, or to gaze on the site of an extraordinary happening. We undertake a pilgrimage to help us remember all the Buddha’s teachings, the quintessence of which is to be found in the four statements he made before he passed away. For us, as Buddhist practitioners, remembering the Buddha isn’t like having a daydream about our teacher; what we’re doing is remembering each and every one of his teachings, because the Buddha is teaching, not just the teacher.

Pilgrimage to India

For hundreds of years, courageous dharma practitioners from Tibet and China devoted large portions of their lives to the long and dangerous journey to India so they could visit the land where the Buddha and great bodhisattvas once lived. Many such pilgrims, having finally arrived at Bodhgaya or Lumbini after months of traveling, unexpectedly experienced remarkable realizations, visions, and dreams. There are marvelous stories about the experiences of these pilgrims: carved stone statues speaking to them; their doubts dissolving the moment they laid eyes on certain holy images or when a gentle breeze caressed their cheeks as they waited to enter a temple. There are stories about practitioners who, by simply looking at the spot under the bodhi tree where Buddha sat, were overwhelmed by the fact that on an ordinary flat stone—not an expensive Italian sofa or jade throne—Siddhartha exhausted the cycle of existence and finished with samsara, bringing to an end the continuous sufferings of rebirth to become the ultimate Jina, or Victorious One. Not only that, but on this very spot the future Buddha, Maitreya, will accomplish exactly the same feat.

It is important for us to remember that making a tour of the Buddhist holy sites won’t solve all our problems in one go, nor will we immediately attain enlightenment. At the same time, we human beings are dependent on the conditions and circumstances in which we find ourselves. As Buddha said, “All phenomenal existence is conditioned, and that conditioning is dependent on motivation.” Conditioning and motivation are the central engines that power the cyclic existence of samsara, and when we are free of them we will also be released from the cycle of rebirth and death to enjoy the freedom known as nirvana. Conditioning has a tremendous impact on us at every level—for example, how we choose to dress, our education, the political system under which we live, the food we eat, the people we hang out with, and the places we visit. Therefore, the holy sites we explore during a pilgrimage will be yet another powerful conditioning influence on us, and a very positive one.

What exactly is the right motivation for going on a pilgrimage? At best, it is to develop wisdom, love, compassion, devotion, and a genuine sense of renunciation (renunciation mind). So, as you set out, you should make the wish that your journey, one way or another, will continuously remind you of all of the great noble enlightened qualities of the Buddha, and that as a result you will accumulate merit and purify defilements.

Initially, the idea of developing a good motivation sounds quite easy, mostly because we approach it with the same habitual assumptions we’ve grown up with. After all, what’s so hard to understand? A motivation is nothing more than a thought, it’s not even an action, so what’s the big deal? You’ll find your attitude changes, though, when you start working with your mind. Most of us find, much to our surprise, that establishing the right motivation is really quite difficult and, certainly at the outset, we struggle.

Once you get better at it, though, you will be able to develop the right motivation from the moment you start to plan your trip. As you pack and shop for diarrhea tablets, excitement mounts because everything you’re doing is part of the process that will take you to the land where the Buddha lived and taught. You’ll be able to see and touch and smell the land where so many of the realized bodhisattvas lived and taught. These days, people go on holiday to Hawaii in search of romance, to Hong Kong for the shopping, or to Rome or London for the culture. You’re traveling to India because you’re inspired by the great and courageous spiritual adventurers who made their homes there—and not just followers of Buddha, but saints and teachers from many of the other great religions.

Of course, for most of us the Buddha is our teacher and our inspiration, and while we may be fascinated by descriptions of his golden skin and ushnisha, such details have little to do with our faith in him. What really arouses our devotion are his teachings and all the rational, logical methods he has offered us for uncovering the truth. As Buddhists, our aim isn’t merely to follow his advice or become his servants; our ultimate goal is to become exactly like him—an enlightened being. So, ideally, our sole motivation and the driving force behind absolutely everything we do, including going on pilgrimage, is the wish to become enlightened.

The backbone of the spiritual method for discovering the truth is mindfulness, and yet the causes of mindfulness are scarce. Followers of the Buddha do everything possible to invoke, maintain, and strengthen their mindfulness, and use all the different gadgets and markers available to remember it—for example, visiting temples, hanging a picture of the Buddha in the living room, reciting sutras and mantras, and listening to, contemplating, and meditating on the Buddha’s words. Any method that reminds us to practice mindfulness is welcome, and our motivation for visiting the holy sites is to take advantage of the profusion of signposts for mindfulness they contain.

Accumulation and Purification

There are many ways of improving our understanding of dharma practice while on pilgrimage, but, for the sake of simplicity, let’s categorize them into the two-fold method of accumulating wisdom and merit, and the purification of defilements.

Whoever we are, the vast majority of us perform two activities almost instinctively: we like to throw out our rubbish and we love collecting goodies. And both activities make us feel as though we’re achieving something. It feels good, for example, to tidy up your bedroom after months of neglect, and to hang a new photo on the wall or fill a vase with fresh flowers; it transforms your mood completely. And this is a universal habitual pattern that can be usefully employed as a format on a spiritual path, where all practices can be presented as being either for purification (throwing out the rubbish) or accumulation (collecting goodies). However, purification and accumulation aren’t two separate things at all; they happen simultaneously, in the same way that when you do your housework, you’re not only cleaning up the mess, but also making your house more beautiful.

Human beings experience mood swings all the time: one minute you’re in a collecting mood, the next all you want to do is clean, and every so often you want to do both. It’s the same when you follow a spiritual path: sometimes you’ll want to stress purification, at other times you’ll want to accumulate merit, and occasionally you’ll want to do both at the same time. On a pilgrimage you should do both as often as possible and in as many different ways as you can. There’s also a long tradition of making pilgrimages for loved ones and those with whom you have a strong connection, good or bad; it’s a very popular practice in traditional Buddhist societies, especially for those who have died, because by dedicating all the hardships you endure throughout your journey, and all the sacrifices you make in terms of your time, energy, possessions, and money, you can purify their negative actions.

How to Accumulate Merit at Holy Sites

Buddhist practitioners always tend to make the same mistakes: they don’t do the small things that accumulate merit, like making daily water offerings, because they imagine them to be trivial and worthless. Yet neither do they make the big gestures, like offering financial support to a Buddhist university for a year, or lighting 100,000 butter lamps every month, or building a temple, because they don’t have the time or the resources. So they end up doing nothing at all.

For beginners, accumulating merit requires effort. For example, a pilgrim from California might consider bringing fresh flowers from their garden to offer at the holy sites in India. It’s not that Californian flowers themselves will accumulate more merit than local Indian flowers, but the effort involved in protecting the flowers throughout the journey from California to India, as well as the money spent in the process, will. At the same time, buying flowers from a little girl at a holy site motivated by the wish to help the child by offering her to the Buddha, will also increase the merit generated by the offering. Or the motivation might be that whoever it is who sells you the offering flowers will, as a result, make a connection with the Triple Gem. This kind of motivation is a profound way to accumulate merit because you are using your own merit as a bridge to connect other people with the Buddha, dharma, and sangha.

Pilgrimage is such a powerful method for accumulating merit that even making the preparations, like saving the money to pay for it and booking time off work, will earn a great deal. If we can also sprinkle our motivation with the dew of bodhichitta, so that everything we do associated with our pilgrimage is dedicated not only to pacifying our own delusion and suffering, but to bringing all sentient beings to enlightenment—the highest aspiration possible—then all the seemingly mundane activities involved, from packing and buying tickets to circumambulating a stupa, become the activities of one who follows a perfect Mahayana path.

People often wonder whether it’s selfish to think about the amount of merit accumulated through good actions. While it’s important to be aware of the risk of being selfish when it comes to accumulation, as a Mahayana practitioner and an aspiring bodhisattva, if you dedicate all the merit you create toward the ultimate happiness and enlightenment of all sentient beings, your actions will be anything but selfish.

Lumbini

Many holy sites are to be found in underdeveloped areas, so be warned, the living conditions won’t compare with those provided on a luxury break in the French Alps. As you arrive at Lumbini in present day Nepal, remember that this was both where Siddhartha was born and where he found himself cornered by the reality of the terrible sufferings of birth, old age, sickness, and death. In some ways it’s not his physical birth that’s of primary importance for a Buddhist pilgrim, it’s that in Lumbini, genuine renunciation was born in Siddhartha’s mind. As a result, he quit his old life completely, leaving his palace, all his wealth and his entire family behind him, including his wife and baby son, which some people considered to be outrageous and cowardly. Those who seek the truth, though, can appreciate the true extent of his bravery; and that bravery, that fearlessness, that audacity, was born in Lumbini.

If your long journey to Nepal has been motivated by spiritual aspirations, taking a few photos and showing an anthropological interest in the holy relics and images won’t be at all satisfying. Instead, make the most of this opportunity to diminish your defilements and bolster your store of merit and wisdom.

There isn’t a specific practice that should always and only be done in Lumbini, but as a follower of the Buddha, what’s best is to emulate him as much as possible. Aspire to learn to appreciate old age, sickness, and death in the same way he did, and to summon the courage to do whatever it takes to go beyond birth and death.

Since a deep sense of renunciation for samsaric life is the key to the spiritual path, cultivate a heartfelt wish that renunciation grows within you so that you won’t be glued to this samsaric world forever. Buddha’s last incarnation as an ordinary human being was as Prince Siddhartha; aspire to make your current life your last, so you no longer have to endure this endless cycle of existence, like a bee in a bottle. And always remember that people like us have buddhanature, no matter how ordinary we may appear to be.

Bodhgaya

Bodhgaya is little more than a shantytown and most visitors are shocked by the dust, the dirt, the beggars, and the poverty—although (unfortunately) the situation is slowly improving. What many people experience once they’ve left the madness and entered the inner circle is that the atmosphere created by the Mahabodhi Temple is so potent it’s as if you fall into a trance. Here you’ll find the vajra seat (vajra asana, also known as the Diamond Seat) where, after many years of searching for the truth and six excruciating years of penance by the banks of the Niranjana River (known today as the Falgu River), Siddhartha finally discovered the Middle Path and achieved enlightenment under the bodhi tree.

The actual tree under which Siddhartha sat was destroyed centuries ago, but a seed found its way to Sri Lanka and a tree was propagated so that later its fruit could be returned to India (there are many wonderful stories about how this seed was acquired) and planted on the exact spot of the original tree. The bodhi tree is important to Buddhists because it is a symbol of enlightenment. In spite of an abundance of trees, caves, and temples in the area, it was in the shade of a bodhi tree that Siddhartha chose to sit, and it was also there that he crushed his final defilements to achieve enlightenment and become the liberator of the Three Worlds—the world of desire, the world of form, and the world of no-form. It is believed that all the one thousand buddhas of this fortunate eon will achieve enlightenment right on this very same spot. All of which means that showing respect for the bodhi tree is not the same as worshiping the spirit of a tree like a shaman, but rather a recognition of the extraordinary event that took place beneath its branches.

Bodhgaya is not only special because it’s where all the buddhas will achieve enlightenment. According to Tantric Buddhism, everywhere in this world and all the phenomena that exist outside ourselves have a corresponding existence within our bodies. Good practitioners and yogis are able, in their practice, to visit the holy places that reside within the chakras and channels of their own bodies, and in this way make progress on their path to enlightenment. Those of us whose practice isn’t quite so advanced can at least visit the outer reflection of these inner holy sites, the heart of which is usually considered to be in Bodhgaya.

Make the most of your time at this holy site. Meditate under the bodhi tree; however short your practice, it will help create in your mind the habit of purifying defilements and accumulating wisdom and merit. Again and again, try to remember the Buddha, dharma, and sangha, and intensify their presence in your mind by reciting prayers, praises, and sutras, and by offering whatever you can afford. While aspiration is of the utmost importance for beginners, rather than making mundane wishes for good health and prosperity, make your main focus the wish that eventually you will sit on exactly the same spot under the bodhi tree as Siddhartha, and achieve exactly what he achieved. It’s also important to remember that no matter how many or how wild our thoughts and emotions, all such defilements are removable.

Vulture’s Peak and the site of Nalanda University are not far from Bodhgaya, and you should try to visit them if you can. For Mahayana practitioners, Vulture’s Peak is particularly significant because it was where the revolutionary science we now know as the Prajñaparamita was taught, which has soothed the anxieties of countless beings and liberated a great many too.

Sadly, only the ruins of Nalanda University still exist. It was one of the first centers of education in the Common Era, as well as one of the greatest, and is an extremely significant place of pilgrimage for students of the Mahayana. The majority of Buddhist teachings still being studied and practiced in Korea, Japan, China, and Tibet were originally notes scribbled on rough slips of paper by teachers and students from this university. In the same way that England’s Cambridge University and America’s Columbia University can boast legions of famous alumni, Nalanda produced a prodigious number of extraordinary spiritual geniuses like Naropa, Nagarjuna, and Shantideva, the great Indian master, scholar, and bodhisattva who is most famous for writing the Bodhicharyavatara (The Way of the Bodhisattva), the classic guide to the Mahayana path. Their contributions to the happiness of millions of people throughout the world are unparalleled.

Varanasi

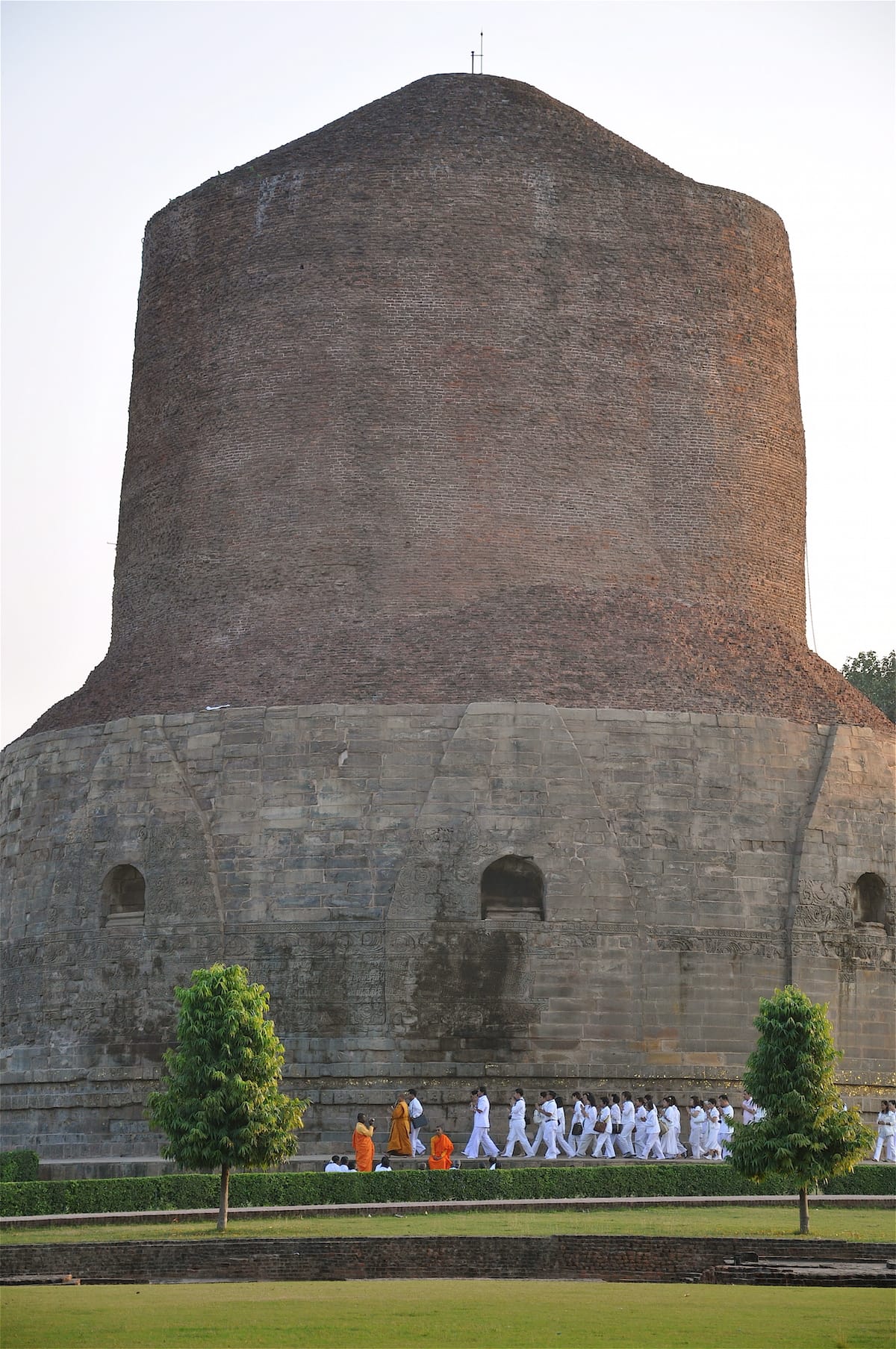

There was a time when Varanasi was a famous cosmopolitan city, and even today Benares, as Varanasi is now known, is held in high regard for its great centers of learning. Sarnath, also known as Deer Park, is quite close to Varanasi and is important because it’s where the Buddha first began to teach everything he had discovered under the bodhi tree.

What the Buddha taught us in Varanasi is that we don’t know what suffering really is. Everything we think will make us happy is either teetering on the edge of suffering or the cause of immediate suffering. It’s relatively easy to recognize the obvious sufferings of this world, but very difficult to perceive that the so-called “good time” some people have in samsara is really suffering or leads to suffering. Buddha pointed out that, contrary to popular belief, suffering doesn’t land on us from an outside source but is a product of our own emotional responses. He made it clear that however much we suffer and however real that suffering and its causes may feel to us, it is in fact an illusion and does not exist inherently. This truth, Buddha tells us, is something we can fully realize for ourselves, and what’s more, he has shown us how by laying out a path for us to follow.

According to the Mahayana, the Buddha not only taught the four noble truths at Sarnath, but countless other teachings too. So, while you’re in Sarnath remember that this is where Buddha first made the path available to people like you and me. And while you’re at Deer Park, by remembering Buddha’s words—for example, the truth of suffering—you will make a connection with the teaching as well as with the place it was taught.

Paying homage to the Triple Gem is always a good practice to do at holy sites, and paying homage to the teachings at Sarnath is particularly powerful. To pay homage to the teachings all you have to do is remember them. Of course, you can’t think of all the Buddha’s teachings at once because they are infinite, so just think of one of them, for example, “All compounded phenomena are impermanent,” and contemplate its meaning for a while. In the same way that swimming in a tiny bay or along the coast counts as swimming in the ocean, thinking about just one teaching the Buddha gave counts as remembering the teachings. If you like you can also read sutras, shastras, and biographies of the buddhas and bodhisattvas, all of which necessarily contain the dharma. Basically, try to remember and appreciate that a path that has the power to transcend samsara and remove all our defilements actually exists.

Kushinagar

Kushinagar is where the Buddha entered parinirvana, and is said to be where he died and his body was cremated. Passing into parinirvana is, of all the Buddha’s teachings, the one that makes the most impact on our minds because it transcends all our concepts about birth, old age, sickness, death, time, increasing, decreasing, samsara, and nirvana. Those of us who have not yet woken up to our true nature are still bound by time, space, quantity, and speed, unlike those who have entered parinirvana and cannot be bound by any kind of dualistic phenomena.

Ultimately, our purpose in following a spiritual path is to experience the awakened state completely free from ignorance, never again to fall back into a samsaric frame of mind. Unfortunately, it’s a state that is extremely difficult to express in words, and it’s also impossible intellectually to grasp its full scope. Nevertheless, by putting into practice the Buddha’s advice about how to wake up, we develop confidence in our experience of the awakened state of mind that entirely transcends dualism, although we’re unable to express our experience to others. It’s like trying to explain to someone who’s never eaten salt what it tastes like; all you can do is name other foods people might be familiar with, and say, “It’s a bit like that.” When you finally realize the simplicity of this state, tremendous compassion for those who remain deeply asleep suffering the nightmare of worldly existence will arise in your mind.

Although we can’t manage to fully achieve the awakened state right now, a glimpse is extremely encouraging for serious spiritual practitioners and helps increase our confidence in the path. Experiences that take us outside our ordinary lives can be particularly heartening, especially as the spiritual path is long, hazardous, and laden with doubt and discouragement. A glimpse of the true nature of reality has the power to make a permanent dent in our samsaric mindstream; at the very least it will serve as an appetizer for the main event. Once we’ve made that first dent, we’ll be able to inflict far more serious damage on the fabric of our samsaric life, and however small the dents and cracks might be, they’re exactly the result a dedicated practitioner is looking for.

Imagine you’re on a picnic near a beautiful lake under a glacier. You dive into the lake with great enthusiasm and swim vigorously away from the shore. Suddenly, you become aware of how cold the water is and how cold your limbs feel. You stop swimming to try to get your bearings, but can’t see the shore at all. Your legs cramp up and your arms are stiff and icy. The seconds pass like hours as you play with the idea that you’re either going to freeze to death or drown.

At the moment you accept that death is inevitable, a local fisherman rows by, drags you out of the water and returns you to dry land, where a warm towel and bowl of piping hot soup await you. During the time it takes you to recover, everything around you that you’d almost lost—your family, your home, your boyfriend—holds far more meaning for you than at any other time in your life, and you become acutely aware that no matter how much you own, death can strike at any moment and doesn’t accept bribes. Sadly, though, the shock wears off relatively quickly and you soon find yourself lured, once more, by promises of happiness in a material world.

The aim of all Buddhist practice is to catch a glimpse of the awakened state. Going on pilgrimage, soaking up the sacred atmosphere of holy places, and mingling with other pilgrims are simply different ways of trying to achieve that glimpse. At Kushinagar you can do all the practices you do at the other holy sites, but perhaps the most significant one to do here is to contemplate Buddha’s statement about impermanence, and if you know how, to meditate on extremelessness or emptiness.

This article is adapted from his pdf book, “What to do at India’s Buddhist Holy Sites,” published by Siddhartha’s Intent, 2010, available at siddharthasintent.org.